The Battle of Midway (Pivotal Moments in American History) (21 page)

Read The Battle of Midway (Pivotal Moments in American History) Online

Authors: Craig L. Symonds

Tags: #PTO, #Naval, #USN, #WWII, #Battle of Midway, #Aviation, #Japan, #USMC, #Imperial Japanese Army, #eBook

The seas were rough. The assistant signal officer on the

Enterprise

, Robin Lindsey, called it the “God damnest weather [he’d] ever seen.” Green water broke over the bow of the

Hornet

, and everyone on deck had to wear a lifeline to avoid being swept over the side. The wind gusted up to 27 knots, and with the

Hornet

making 30 knots, the relative wind speed over the deck was 50 knots or more. Despite the choppy seas, that wind was a blessing, for it would aid in getting the 31,000-pound bombers into the air. Navy Lieutenant Edgar Osborne stood near the bow with a safety line around his waist and a checkered flag in his hand. Sea spray soaked him each time the big carrier plunged into another wave. He watched the majestic rise and fall of the

Hornet

, waving the black-and-white checkered flag over his head in a circle as a signal for Doolittle to rev his engines. Then, just as the

Hornet

reached the nadir of its plunge, Osborne slashed the flag downward. Doolittle released the brake, and his B-25 surged forward. He kept the nose wheel on the white line painted on the

Hornet’s

flight deck. If he kept it steady, his right wing tip should clear the superstructure of the ship’s island by six feet. The plane raced downhill at first, and then, as the

Hornets

bow rose up again, his plane rose up with it and was boosted into the sky with plenty of flight deck to spare. It was exactly 8:20 a.m.

32

Doolittle made one pass over the ship, then flew off on the coordinates he had calculated. He did not circle to wait for the rest of the planes to join him. To do so would waste precious fuel, especially since they were launching nearly a hundred miles beyond optimum range. Flying in formation used up additional fuel, since every pilot except the leader had to make constant tiny adjustments to hold his position. Instead, each plane would make its way to the target independently.

33

The rest of the planes took off at intervals of several minutes. The second one almost didn’t make it. Lieutenant Travis Hoover’s plane dropped off the end of the deck and disappeared. After a few harrowing seconds, it appeared again, struggling up into the sky. The rest of the launchings were mostly routine—as routine as launching two-engine land bombers off a carrier could be. Until the last one. The tail of the sixteenth plane extended out over the back of the

Hornet’s

fantail, and the plane had to be wrestled forward to the launching spot by the deck crew. The wind continued to gust unpredictably. One particularly severe gust caught Seaman Robert W. Wall and threw him into the left wing propeller. His arm was badly mangled and later had to be amputated. But the plane left on time.

34

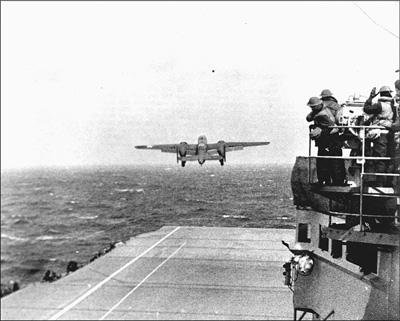

Doolitt le’s B-25 Mitchell bomber takes off from the deck of the

Doolitt le’s B-25 Mitchell bomber takes off from the deck of the

Hornet

on April 18, 1942. Note the white line painted on the flight deck to help the pilots avoid hitting the ship’s island superstructure. (U.S. Naval Institute)

As soon as the last plane was airborne, Halsey ordered the carriers and cruisers to reverse course and steam east, away from Japan, at 25 knots while the crew turned its attention to bringing up the planes from the hangar deck so that the

Hornet

could function as a real carrier again. As Doolittle and his bombers flew westward, Halsey and Task Force 16 sped away eastward.

The Army pilots, accustomed to navigating over land by following railroads or highways, were now flying over 650 miles of open ocean toward a target none of them had ever seen. They had practiced for the mission by flying out over the Gulf of Mexico, learning to fly by compass bearing alone. To conserve fuel, they flew at 165 knots, replenishing the tanks by hand from gas cans stored on board, saving the cans to throw over the side all at once, so that they didn’t form a trail on the surface of the sea for the Japanese to follow. About a half hour into the flight, Taylor’s Number Two plane caught up to Doolittle and settled in on his wing, though the rest headed for Japan independently. They flew low, about 200 feet, and passed over some small ships, mostly fishing vessels, though Doolittle thought he saw a light cruiser. Doolittle made landfall well north of Tokyo—navigating by dead reckoning was always a bit dicey. Instead of following the coast southward, as some did, he decided to fly inland and approach the target from the north. He was still flying low, the shadow of his plane jumping around on the ground as it conformed to the topography. He passed some small biplanes—perhaps army trainers—but there was no reaction from them. Other pilots recalled flying over groups of civilians who looked up and waved, assuming, not unreasonably, that these were Japanese planes on a training mission. One plane flew over a baseball field with a game in progress, and the crowd stood up to wave. The pilots waved back.

35

Ten miles north of Tokyo, Doolittle encountered nine Japanese fighter planes flying in three tight V formations. They ignored him. At the outskirts of the city, Doolittle pulled up to 1200 feet, turned southwest, and dropped his first bomb at 1:30 p.m. (ship time). He had been flying for five hours. After dropping his four 500-pound bombs, Doolittle took his plane back down to 500 feet. There was a lot of antiaircraft fire now, though it was inaccurate; at 500 feet his plane was a difficult target. He passed over an aircraft factory where new planes were lined up in rows outside, but he had no bombs left, and he continued southwestward out over the Sea of Japan and on toward the China coast.

36

He made landfall at dusk; soon it was full dark. He was now flying over unknown terrain with no certain objective. Doolittle pulled up to 8,000 feet to avoid running into a mountain and flew on. At 9:00 p.m., after covering 2,250 miles in thirteen hours, he was running out of gas. He got no response on the radio frequency he had been given for the Chinese airfields. He did not know that news of his mission had never made it to the Chinese. At 9:30, he ordered his crew to prepare to jump. He ensured that they went first, and then, setting the autopilot for level flight, he followed them out into the night.

37

He landed in a rice paddy that had recently been fertilized with human excrement. After slogging his way to solid ground, he knocked on the door of a small house where a light was showing, and tried out the phrase that the Chinese-speaking Lieutenant Stephen Jurika had taught all of them during the Pacific crossing:

Lushu hoo megwa fugi

: “I am an American.” The only response he got was the dousing of the light and the bolting of the door. He walked on. The next day, after a night trying to stay warm, he encountered three Chinese soldiers. He drew them a picture of an airplane with parachutes coming out of it. They were skeptical at first but relaxed when they found his parachute, which the unwelcoming farmer had secreted in his house. After several days, they got him to Hang Yang Airfield, and from there he, and eventually most of the others, were flown to the Nationalist Chinese headquarters at Chungking. There they were presented with presidential congratulations and notification that each of them would be awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Three weeks later, in a small and secret ceremony in the White House, President Roosevelt awarded Doolittle the Medal of Honor.

38

All sixteen American bombers had successfully found their targets, hitting Yokohama, Nagoya, and Kobe as well as Tokyo, but none of them had landed safely on Chinese airfields. One landed in southern Russia after its skipper, Captain Edward York, discovered that he did not have enough fuel to make it to China.

*

The rest crash-landed somewhere in China or along the Chinese coast. Of the eighty Doolittle raiders (five men per plane), seventy-three eventually made it back to the United States—though it took a while for some of them. Two died when their plane crashed, and another was killed bailing out. Eight were captured by the Japanese. Of those, three were executed, one died in prison, and the others survived the war in a POW camp. The crew of Captain York’s plane was interned in Russia. Just over a year later, those five escaped from the Soviet Union into Iran and eventually made it back to the States.

For their part, the Japanese made light of the Doolittle raid, punning on his name to claim that his handful of bombers had done little to hurt the great empire, which was true enough. The American pilots had hit an oil tank farm, a steel mill, and power plants; one bomb slightly damaged a brand-new carrier—the

Ryūhō

—still in the shipyard. But they also hit several schools and an army hospital. Naturally, Japanese newspapers declared that the bombers had targeted schools and hospitals to “kill helpless children,” the usual wartime propaganda. Despite their defiant pronouncements, however, the Japanese high command was humiliated; the ability of the Imperial Army and Navy to protect the life of the emperor had been called into question. The Doolittle raid did not trigger the Midway expedition—that decision had already been made. It did, however, remove any doubts the Army had about backing the operation. According to Watanabe, “With the Doolittle raid the Japanese Army changed its strategy and not only agreed to the Midway plan of the Navy but agreed to furnish the troops to occupy the island.”

39

In the United States, news of the raid was received jubilantly. Americans thought of it as payback for Pearl Harbor. One might note that the Americans had lost all sixteen bombers, one more plane than the Japanese had lost in the American air victory off Rabaul on February 20. Still, there had been so little good news in the war so far that the Doolittle raid inspired both celebration and speculation about how those planes had managed to cross the Pacific. Though the Japanese learned from the captives that the bombers had been launched from a carrier, that fact remained an official secret for more than a year, and when asked where the planes had taken off, Roosevelt answered puckishly that they had flown from “Shangri-La,” the mythical and mystical city of James Hilton’s popular novel

Lost Horizon

. In homage to that, one of the new

Essex

-class carriers then under construction would be christened

Shangri-La

.

Halsey’s Task Force 16 arrived back in Pearl Harbor on April 25. Mitscher had hoped to grant liberty to the crew of the

Hornet;

its men had been at sea almost continuously since leaving Norfolk. But with only four American carriers in the Pacific, there was no time for that. The men of the

Hornet

and

Enterprise

, as well as their escorts, had to forego leave in Hawaii, just as the men of the

Shōkaku

and

Zuikaku

had to forego leave in Japan. The Japanese sailors on their two carriers were bound on a special mission. And thanks to a handful of men working secretly in the basement of the Fourteenth Naval District headquarters building in Pearl Harbor, the Americans knew what that mission was.