The Giants and the Joneses (2 page)

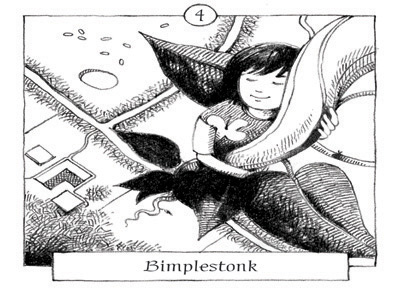

Bimplestonk

F

OR THE SECOND

time in her life, the girl giant climbed over the wall. Then she turned and looked back down the narrow road. She couldn’t see far because of the mist, but she didn’t think anyone was following her.

Thank goodness her horrible spying, prying brother Zab was safely away at boarding school.

No one had seen Jumbeelia yesterday, either, when she came this way and threw the bimple off the edge of

Groil. No one had heard her urging it to grow: ‘Eep, bimple, eep!’ At least, she didn’t think so. But what about old Throg? Could he have been lurking around somewhere? Was he here now, hidden behind one of the huge boulders which she could only just make out through the mist?

It was Throg’s rhymes, as well as the bedtime stories about the iggly plops, which had brought Jumbeelia here, but she certainly didn’t want to bump into the strange old man.

She shivered. The air was colder today, and the mist grew thicker with every step she took. Soon she could hardly see anything – not even her hand when she held it out in front of her, not even her feet as they shuffled along the hard ground.

There wouldn’t have been much to see anyway. No trees grew here in the cloudy edgeland; no flowers, no grass, nothing at all. The rocky ground was bare and smooth, even a little slippery.

It wouldn’t do to slip – not so near the edge of Groil. Jumbeelia shuffled slowly, feeling with her feet for the place where the ground stopped and the emptiness

began … the emptiness which she hoped would not after all be quite empty.

Here it was, sooner than she remembered. She stopped. And yes! Surely there

was

something looming out of the mist.

‘Bimplestonk!’ she murmured, full of wonder.

Jumbeelia reached out. She didn’t have to reach far. Almost immediately her fingers touched something damp and cool and floppy – a leaf! And now her hand was curling round a thick firm stalk.

It was the loveliest thing she had ever seen or felt.

‘Beely beely bimplestonk!’

So it was true! A bimple could grow into a bimplestonk overnight. And if that was true, surely the rest of the story must be true! Jumbeelia reached out with the other hand. And then her feet followed her hands …

Down she climbed. ‘Boff, boff, boff!’ Down, down, down through the clouds. Down, down, down to the land of the iggly plops. And when she was out of the clouds she could see it spread out below her, a patchwork of iggly green fields, with darker green blobs

which must be woods, and threads of cotton which must be roads.

Of course, things always looked iggly from a distance. Maybe when she reached the ground everything would be the same size as in Groil.

But no! Here she was at the very bottom of the bimplestonk. She unclasped her hands and stepped out on to grass as short and fine as giant eyelashes. ‘Iggly strimp!’ she cried.

And then she noticed something much more wonderful. A few strides away, nibbling at the strimp, were some woolly creatures the size of mice. But they weren’t mice, of course – they must be sheep.

‘Iggly blebbers!’

Jumbeelia took her collecting bag off her back. It wasn’t a very big bag but it had several pockets. She picked up one of the blebbers. It wriggled and bleated as she put it gently into one of the pockets. She put in a few tufts of strimp too, hoping that the blebber would settle down and eat them.

Excitement bubbled up inside her. Where there were blebbers there were bound to be plops.

She made her way across a few fields, stepping over the ankle-high hedges and splashing through a pond as shallow as a puddle.

She strode along a lane and came to a pillar box.

‘Iggly pobo!’ She picked it up and thrust it into a pocket of the bag.

She turned a corner and saw a telephone box.

‘Iggly frangle!’ she cried as it went into another pocket.

Round the next corner was something even better – a cluster of iggly houses. She couldn’t see any plops, but in the nearest garden was a swinging seat covered in cushions.

‘Iggly squodgies!’ Into the bag they went. They would make a nice soft floor for the iggly plops. Surely,

surely

she would find some iggly plops soon.

But the other gardens were disappointingly empty, and though she peered in through the windows of the houses and saw lots of sweet iggly furniture there was not an iggly plop to be seen.

Jumbeelia began to worry that Mij would have woken up from her afternoon nap and be missing her. Maybe she should go home and come back another day. After all, she had plenty of other iggly things to play with – the pobo, the frangle, the squodgies and, best of all, the beely woolly blebber. The blebber had stopped bleating and she could hear it munching the iggly strimp. She couldn’t wait to offer it some proper giant-size strimp.

She was about to turn around when she noticed another house on its own about half a mile down the lane.

Ten strides and she was there. The front garden was empty, but when she saw what was in the back garden she gave an excited skip which set the blebber bleating all over again.

A machine was sitting in the middle of the lawn. ‘Iggly strimpchogger,’ she whispered in delight.

But even more exciting were the three creatures she could see – one of them in the seat of the strimpchogger, the other two nearby, bent over an iggly cardboard box.

Jumbeelia counted to herself: ‘Wunk, twunk, thrink iggly plops!’

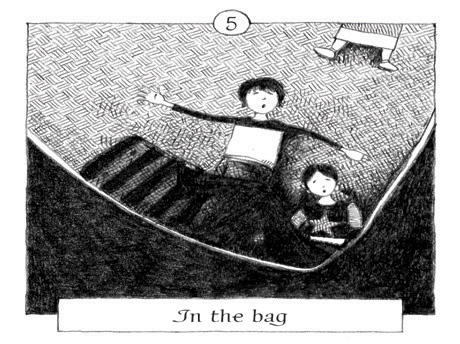

In the bag

‘W

HERE ARE WE

?’ Stephen’s voice sounded shaky and his face was white.

Colette looked round at the blue canvas walls of their prison. She shuddered, remembering the fat pink tentacles that had put her there.

‘I think we’re in a giant’s bag,’ she whispered back.

‘Don’t talk rubbish – giants don’t exist.’

But the next second they heard a deafening voice.

‘Beely iggly plop,’ it said, and the tentacles appeared

above them, with Poppy in their grip.

Poppy was laughing. ‘Big girl do it ’gain,’ she said as the giant hand released her. She seemed to think this was some new kind of glorious fairground ride.

‘It’s not a girl, it’s a giant, silly,’ Stephen snapped at her. ‘It’s probably going to eat us.’

But Poppy just repeated, ‘Big girl,’ and started bouncing on the cushions which covered the floor of the bag.

And then the canvas ceiling came down.

‘All dark,’ complained Poppy.

Colette felt sick with fear, but she managed to find her voice, and shouted, ‘Stop! Let us out! Let us

out

!’

‘It can’t understand you. Didn’t you hear it? It speaks a different language.’ Stephen sounded angry, as if the whole thing was her fault.

A tremendous jolt threw them up into the air and down again. As the three of them rolled helplessly about on the cushions, Poppy giggled again. But Colette and Stephen were silent. They both knew what was happening. The giant was on the move.

‘Mum! Dad! Help!’ yelled Colette, but without much hope.

A sudden swoop and a bump, and the jolting stopped. Their dark ceiling was off again, and light streamed in.

‘Maybe it’s going to put us back?’ said Colette.

‘Maybe it’s hungry,’ said Stephen.

The hand came down – but not to take them out.

‘It’s putting something in,’ said Colette.

‘Peggy line!’ said Poppy.

‘Iggly swisheroo!’ said the voice.

‘Can’t

anyone

round here speak English?’ said Stephen. ‘It’s a washing line.’

And so it was – quite a long one, complete with pegged-out clothes, towels and sheets. A sheet landed on top of Colette and by the time she had struggled free the bag was dark and the bumpy journey had begun again.

Poppy, delighted with this new and grown-up toy, started unpegging the clothes and hoarding the pegs in a corner of the bag.

‘Oh no, not you too,’ said Stephen in disgust. ‘Isn’t one collector in this family enough?’

Colette turned on him. ‘Do shut up,’ she said. ‘Can’t you

ever

stop complaining?’

‘Yes,’ said Stephen triumphantly. ‘I’ll stop complaining when you stop collecting.’

Colette could hardly believe this. Here they were, jogging along in the dark, inside a giant’s bag, and yet they were still squabbling.

Before she could think of a cutting retort, there was a terrifyingly loud noise right in her ear – a long, low grating kind of noise which seemed to come from within the bag itself. Colette found herself clutching Stephen despite their quarrel.

‘What was that?’ she said.

‘Baa Lamb,’ said Poppy.

‘This isn’t the time of year for lambs,’ said Stephen in his Mr Know-All voice. ‘Anyway, its bleat is too low-sounding. It’s a sheep.’

As if in agreement the low bleating was repeated. It was just behind one of the canvas walls.

‘Big girl got Baa Lamb,’ said Poppy stubbornly.

‘Big girl got great enormous sheep, you mean,’ said Stephen. ‘Probably for supper. Or maybe we’re

supper and the sheep is breakfast.’

Poppy started to cry then. Colette put an arm round her. ‘Well done, Stephen,’ she said.

‘I’m sorry. I’m sorry, Poppy,’ said Stephen, who hardly ever apologised. Colette noticed that his voice was shaking again. ‘I just wish I could get us out of here … I know! Give me one of those clothes pegs, Poppy.’

Poppy sniffed and handed him one. Stephen started picking away with it at a corner of the bag as they jolted along.

‘What are you doing?’ asked Colette.

‘I can feel a little hole here, where the stitching has come loose. If I can make it bigger maybe we can escape.’

‘But we’d get killed jumping.’

‘She might put the bag down again,’ said Stephen, still hacking away. ‘There – it’s big enough to look through, at least.’ He lay on his tummy and put his eye to the hole.

‘Oh no,’ he said.

‘What is it?’ asked Colette.

‘You’d better have a look.’

So Colette looked through the hole and was overcome with dizziness and fear.

‘Is it what I think it is?’ she said.

‘Yes. We’re going up a beanstalk.’

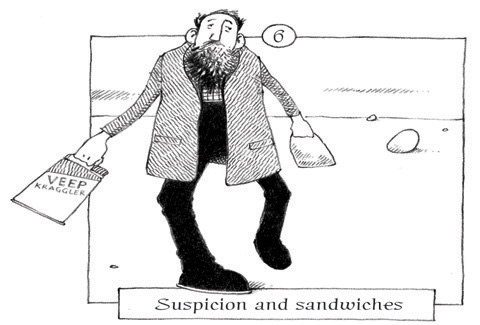

Suspicion and sandwiches

Arump o chay ee glay, glay,

Arump o chay ee glay.

Oy frikely frikely bimplestonk,

Eel kraggle oy flisterflay.

O

LD

T

HROG HOBBLED

along, reciting his favourite rhyme and swinging his can of weedkiller in one hand and his sandwich bag in the other. His voice was

faint and cracked, and he felt tired and cold. The mist was thicker than usual today, so thick that it might be difficult to make out a bimplestonk if one had eeped up during the month or so since he had last walked along this stretch of the edgeland.

It was time for his afternoon nap, Throg decided. He climbed over the wall, emerging out of the edgeland mist into a sunny field. It was good to warm his old bones, eat a sandwich and doze off for a few minutes, but he knew that his dreams would be troubled, as they always were. What if the bimplestonk appeared and the iggly plop invasion took place while he was asleep?

Throg woke with a start. Someone really

was

coming, he sensed it in his bones.

It was all right. It was just a girl, with a bag on her back. Throg recognised her as the daughter of one of the useless policemen who refused to take the iggly plop invasion seriously.

The girl was walking along the narrow road which ran from the edgeland towards the main town. What had she been doing all by herself so near the emptiness?

‘Wahoy!’ he called out to her in his thin old voice, but the girl didn’t seem to hear his greeting. She continued on her way, and Throg noticed that she had a huge grin on her face.