The Grand Ole Opry (23 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

MAN OF THE YEAR

C

ountry music was slow coming to records because the manufacturers believed that even if “hillbillies” bought records, they

really wanted pop or classical music rather than their own music. Similarly, radio stations didn’t think “hillbillies” would

support their advertisers until the Opry helped to prove them wrong. And country music was equally slow coming to television

because the signal didn’t reach rural areas . . . and because the sponsors didn’t think that “hillbillies” would buy their

products.

Network television started in 1949, and by 1954 more than half of American homes had a television set. WSM launched its television

station in 1950 and produced a country music show for local consumption, but country music didn’t come to network television

until 1955. And the first networked country show wasn’t the Grand Ole Opry.

Jean Shepard sings for the camera on the Purina Opry show, produced by WSM-TV for ABC.

After Red Foley left the Opry in 1953, he was approached by KWTO in Springfield, Missouri, to host a new radio barn dance,

the

Ozark Jubilee.

From the beginning, the plan was to take the

Jubilee

to television, and on January 25, 1955, it went out on the ABC-TV network. Its success encouraged ABC to schedule three other

television shows,

The Pee Wee King Show, The Eddy Arnold Show,

and the

Grand Ole Opry.

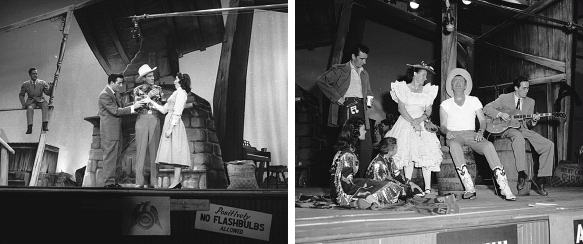

left: Little Jimmy Dickens observes Tony Bennett, Ernest Tubb, and June Carter.

right: Buddy Ebsen with Minnie Pearl, Carl Smith, Chet Atkins, and the Collins Kids, Lorrie and Larry.

Purina sponsored the Opry on ABC-TV, but rather than film the Saturday night radio show, Purina insisted upon staged sets

with merry-go-rounds, hay bales, and noncountry guests such as Tony Bennett, Buddy Ebsen, and opera singer Marguerite Piazza.

The Purina Opry show went out in the 1955–56 season, but didn’t return, while the

Ozark Jubilee

remained on ABC-TV until 1960. In a high-stakes game, the Opry had lost ground early on.

In the fall of 1954, the Opry had missed another opportunity. Less than three months after his first record was released,

Elvis Presley played a guest spot on the Opry, and could have been signed to the show. Like many rock ’n’ roll singers, he’d

grown up listening to the Grand Ole Opry.

Elvis Presley’s first single, “That’s All Right”/“Blue Moon of Kentucky,” was released in July 1954, and became enough of

a sensation in and around Memphis for his record company, Sun Records, to pull a few strings and get him a guest spot on Hank

Snow’s portion of the Grand Ole Opry. “Blue Moon of Kentucky” was a song that Bill Monroe had written and recorded in 1946,

and Elvis was worried that his rockabilly version would annoy the legendarily irascible Monroe.

BILL MONROE:

He come up to the Grand Ole Opry one time and come in the dressin’ room where I was at. He apologized for the way he had changed

“Blue Moon of Kentucky.” I told him, “Well, if it give you your start, it’s all right with me.”

BUDDY KILLEN,

Opry bassist:

I noticed a young man standing off to the side. He looked fearful and lost, shaking and pacing with his guitar on his back.

“Hi,” I said, “I’m Buddy Killen. I play bass on the Opry.” “Hi,” he sort of mumbled, “I’m Elvis Presley. If Sam Phillips would

let me leave, I’d git out of here. These people are gonna hate me.” Phillips was his record producer and the owner of Sun

Records. “You’ll do fine,” I assured him, and hoped he would.

SCOTTY MOORE,

Elvis’s guitarist:

They wouldn’t let us do but one song, and that had to be “Blue Moon of Kentucky” because it was a country song. The audience

reaction was very slight. They applauded. They didn’t go wild. There wasn’t any booing or hissing. Just polite applause. It

wasn’t as bad as people have written it up to be. After we did the song and went offstage, Jim Denny, according to Elvis,

made the comment, “You better keep driving the truck.”

BUDDY KILLEN:

There was no earthshaking response. He didn’t bring the house down and there was no encore. Years later, there was a motion

picture supposedly portraying the event. In the film, Jim Denny suggested that Elvis not give up his day job. The truth of

the matter is that Denny did nothing of the kind.

Before long, the checks for “Blue Moon of Kentucky” made their way to Monroe. “They was powerful checks,” said Monroe. “Powerful

checks.”

Two weeks after his Opry tryout, Elvis joined the Opry’s major rival, the

Louisiana Hayride

in Shreveport, and used the show as a springboard to success. In July 1955, he toured Florida with Hank Snow. By then, Eddy

Arnold’s former manager, Colonel Parker, was managing Snow through a jointly owned company. Using Snow’s name to impress Elvis

and his parents, Parker booked Elvis and eventually took over his management, edging Snow out of the picture in the process.

Colonel Parker and Hank Snow hired a publicist, Mae Boren Axton, who wrote songs as a sideline. In October 1955, Mae brought

her songs to Nashville in search of a music publisher. The publisher usually tries to place songs with artists, but Mae already

had an artist in mind for one song.

MAE AXTON:

I went to one well-known publisher, and said, “I’ve got a song here that will sell a million.” One of his associates just

laughed. That night at the Grand Ole Opry, I saw Jack Stapp. He said, “Mae, you never have offered me a song. Why?” “I’ve

got one for you now, it’s ‘Heartbreak Hotel,’ ” I replied. “I’ll take it,” Jack answered. He’s a busy man at the Opry, as

you know. I came back in November for the Opry-sponsored disc jockeys’ convention. I saw Elvis in the Andrew Jackson Hotel

lobby. I told him, “Elvis, I got a song you are going to listen to right now.” He said, “I can’t do it, I’ve got to go to

a meeting.” But I insisted. We went to my room and played the song. He said, “Hot dog, Mae, play that again.”

Still on Sun Records, Elvis was in Nashville at WSM’s Disc Jockey Convention to showcase his act for RCA. Just a few days

after the convention, RCA purchased his contract, and “Heartbreak Hotel” became his first RCA single . . . and first nationwide

hit. The Opry made a point of signing the next major star on Sun Records, Johnny Cash.

Elvis at the 1955 Disc Jockey Convention.

left: Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Two, Marshall Grant and Luther Perkins.

right: Johnny Cash signs autographs backstage at the Opry.

BEN A. GREEN,

in the

Nashville Banner,

July 14, 1956:

Tension gripped the big Ryman Auditorium stage as young Johnny Cash stepped forward to “achieve his life’s ambition,” and

sing on the Grand Ole Opry. You could feel the charged atmosphere—some folks in the wings held their breath. All of the Opry

people were pulling for this newest member of their family to score big with the 3,800 folks looking on and millions more

listening in from coast to coast. He had a quiver in his voice, but it wasn’t stage fright. The haunting words of “I Walk

the Line” began to swell through the building, and a veritable tornado of applause rolled back. The boy had struck home. One

onlooker told us, “He’ll be every bit as good as Elvis Presley. Probably better, and he’ll last a whole lot longer. He has

sincerity, tone, and he carries to the rafters.” Johnny Cash, just 11 months into his career, is one of the youngest stars

ever to reach the Grand Ole Opry. What was his reaction? “I am grateful, happy, and humble,” he said. “It’s the ambition of

every hillbilly singer to reach the Opry in his lifetime.”

JOHNNY CASH:

I remember something Ernest Tubb told me in 1956 the first time I met him. It was a big-deal night. I’d just encored on the

Grand Ole Opry, and now I was meeting Ernest Tubb live and in person. He looked at me and he said in that grand, gravely voice

I’d been hearing on the radio, “Just remember, son, the higher up the ladder you go, the brighter your ass shines.”

DOLLY PARTON:

I waited for him in the Ryman parking lot. A man stepped out of the stage door and walked over to us. There was only me and

Johnny Cash. I had never seen a man with such presence. Tall, lanky, and sexy with that trademark voice that cut through me

like butter. Now I knew what star quality was. I was just a thirteen-year-old girl from the Smokies, but I would have gladly

given it up for Mr. Cash right there in the parking lot. I found myself blurting out, “Oh, Mister Cash, I’ve just got to sing

on the Grand Ole Opry.” I know he must have heard that all the time, but he looked at me as if he was thinking, You know this

kid is really serious.

In spite of the addition of Johnny Cash to the Opry roster, Elvis’s continued success presented the Opry with the biggest

challenge it had faced in its thirty-year history.

WESLEY ROSE

of Acuff-Rose Publications:

“It was a very dangerous time. In all the years I’ve been in the business I’d say it was the most critical time for country

music. Elvis Presley broke out. They were playing him on all stations. By playing rock artists on country stations, the country

listeners began to tune out, and then the country programs began to disappear. We had six hundred stations playing country

music, and it got down to around eighty-five stations.”

Compounding the Opry’s problems, there was a crisis within management. Edwin Craig and Jack DeWitt saw WSM’s employees starting

sideline businesses that relied to a great extent on their employment at WSM. Jim Denny and Jack Stapp owned music publishing

companies, and three WSM engineers owned Castle Recording Laboratories. Under pressure from WSM, Jack Stapp gave up ownership

of Tree Music, for a while at least. The engineers were offered roles at WSM-TV if they gave up the studio, and they accepted.

Jim Denny was offered a pay raise and the job of formally managing the Opry if he gave up Cedarwood Music, and the situation

came to a head on September 26, 1956.