The Grand Ole Opry (25 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

GRANT TURNER:

Judge Hay was still there. He was in charge of answering fan mail. [His official title was Audience Relations.] Someone had

written a song, someone wondered what kind of mandolin Bill Monroe played, or what was Cousin Wilbur’s last name. Did Uncle

Dave Macon eat country ham three times a day? And he conducted auditions on Tuesday mornings around ten o’clock. The Judge

would bow his head as if in deep thought, remove his glasses and put pressure on his nose with his thumb and forefinger. Finally,

he would lift his head and look the singer full in the face. He’d say, “Friend, I want to thank you for coming by today. We

have a full roster of singers just now, so let me ask you to go back home.” But Stonewall Jackson was one Opry star that was

hired in this way. I remember him standing in the corner of the studio with no microphone, and singing for the Judge.

The Grand Ole Opry cast, 1956, with Judge Hay in front.

Stonewall had been farming in Moultrie, Georgia, and drove his farm truck to Nashville wearing his workday clothes. He had

never performed on radio or recorded, and had no idea of what it usually took to get on the Grand Ole Opry. Driving up Franklin

Road, he saw Acuff-Rose Publications and took a room across the street at the York Motel.

WESLEY ROSE:

One afternoon, we heard some guitar pickin’ and singin’ across the street in the motel. Then this guy came over and played

songs for us. It was Stonewall Jackson. He was glad we liked the songs, but he said, “Mister Rose, I came here for just one

purpose: to get on the Grand Ole Opry. Can you get me an audition?” I told him, “You can’t get on the Opry unless you’re on

a record label. That’s a rule.” “Mister Rose,” he answered. “You get me an audition, I’ll end up on the Opry.” He was so young

and so country and so appealing. I said, “I’ll try, but don’t get your heart broke if they don’t take you.” It couldn’t happen

again in a million years. Back when we tried to get Hank Williams on the Opry, we had to work on it for three months, and

he had hits at the time. Stonewall never had any records, but he just went down and knocked ’em out.

STONEWALL JACKSON:

The first phone call I ever got in Nashville was from Wes Rose. He’d got me an audition at the Opry. I went down and auditioned

with Judge Hay the next morning at nine o’clock.

What happened next was both a fairy tale come true . . . and a bitter wake-up call for a young entertainer fresh off the farm.

D. KILPATRICK,

letter to WSM management, December 10, 1958:

On October 19, 1956, Judge Hay requested that I personally audition Stonewall Jackson. The audition was around three p.m.

and Stonewall was immediately employed on a temporary basis. I left for dinner around 5:30 p.m., and upon returning I observed

a man named John Kelly talking to Stonewall in the entrance room of Studio B. It came to my attention that Stonewall signed

a management contract with Kelly whereby Kelly would receive one third of Stonewall’s gross income and revenue. On November

2, I had Stonewall and John Kelly in my office to explain that such a contract was prohibitive and not to the best interest

of the artist or the Grand Ole Opry. I told Kelly that we didn’t want to build an artist who was currently making little or

no money, then to have the artist become a money-maker and be frustrated and bitter as a result of such a commitment made

at an early stage of his career. This has happened to other Opry artists. If there ever was a greenhorn, it was Stonewall,

but his natural simplicity and his extreme desire to sing, plus his ability to render a song charmed both Judge Hay and I.

After much discussion, Kelly agreed to release Stonewall from his contract. Jim Denny stated to me that Kelly had caused him

considerable trouble when he, Denny, was head of WSM’s Artist Service. Denny stated that he had personally threatened to run

Kelly out of town.

STONEWALL JACKSON:

I was wearin’ patched khaki farm clothes and a beat-up hat. Ernest Tubb introduced me. He said, “Here’s a brand-new guy, just

got in town from Georgia in his pickup truck. We hear that he sings a good country song, and we’re all gonna be rooting for

him. Here’s a brand-new singer, you’ve never heard tell of him before. Here’s Stonewall Jackson from down in Moultrie, Georgia.”

Ernest could build you up. He could make you look like a star by the time you hit the stage. The other artists were snickering.

They thought the Opry had hired a new comedian, so they were ready to put the laugh on. I thought, “Man, this ain’t workin’

so good. It’s now or never,” so I just lit into it. I sang that sucker as good as I could sing, and the band got into it.

Everybody got quiet. Ernest had to bring me back out four times. I felt accepted then.

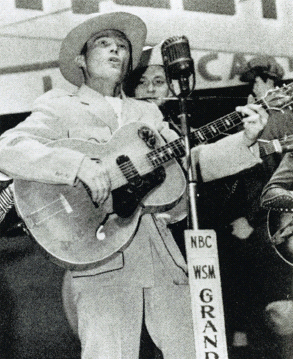

An early Stonewall Jackson appearance.

Kilpatrick was on safer ground approaching Porter Wagoner at the Ozark Jubilee. Porter tried to position himself so that he

could work both shows, but Kilpatrick forced the issue, and in March 1957, Porter moved to Nashville to join the Opry. Kilpatrick

also hired Wilma Lee and Stoney Cooper from the Wheeling, West Virginia, Jam-boree. Other new hirees during the 1950s included

Don Gibson, Billy Grammer, the Wilburns, Hank Locklin, Bill Anderson, Skeeter Davis, and George Hamilton IV.

Some of the younger artists, like Johnny Cash and the Everly Brothers, quickly found it impossible to meet their Opry commitments.

They were on coast-to-coast tours and couldn’t afford to give up a lucrative Saturday night showdate to fly back to Nashville

at their own expense to appear on the Grand Ole Opry. The Opry was still the dream of every country music performer, but the

reality of membership led to persistent squabbles. Marty Robbins lashed out against the Opry’s restrictions and quit more

than once, but nevertheless saw the show’s value in building a career and returned.

New Opry star Don Gibson with Minnie Pearl.

BILL MAPLES,

journalist, 1958, in the

Tennessean:

Robbins was fired last Saturday after his performance on the Opry’s Prince Albert Show. A station official quoted Robbins

as saying he did not need the Opry. Robbins said he did not say this, but did criticize management. But Robbins and WSM patched

up their quarrel and Robbins joined the Grand Ole Opry again. In returning to the Opry, Robbins will not benefit so much financially

as he will from the prestige of the show and from its nationwide coverage by radio. Opry musicians are paid union scale which

is $30 for leaders and $15 for supporting musicians.

Skeeter Davis, who joined in 1959, became best known for her 1963 crossover hit, “The End of the World.”

When Marty Robbins topped the pop and country charts with “El Paso” the following year, the trouble resumed.

D. KILPATRICK

memo to Jack DeWitt, January 15, 1959:

Robbins’ demand that his vocal trio be used couldn’t have been worse. Our acts use four musicians and sometimes less, so we

can’t allow Robbins to use eight other than himself. Before Roy Acuff’s departure for Europe, Robbins personally berated Acuff

for consistently plugging the Opry and WSM on personal appearances. Robbins’ statement to Acuff was, “What the hell have they

done for you?”

As hard as Kilpatrick tried to stand his ground, he knew that his bargaining position wasn’t good. “Live” radio was fading

into memory, and, one by one, the other radio barn dances folded. The Old Dominion Barn Dance closed in 1957, and the WLS

National Barn Dance, together with the Ozark Jubilee and the Louisiana Hayride closed in 1960. Out in Cali-fornia, Home Town

Jamboree closed in 1959 and Town Hall Party in 1961. The Opry lost its Prince Albert network sponsorship in 1960, but hung

tough.

BILL ANDERSON:

The other shows didn’t have the commitment from above. Edwin Craig was still there and he wanted to keep the Opry alive. The

other thing that the Opry did, whether intentionally or not, was to be bigger than any individual star. Elvis was so big at

the Louisiana Hayride, but when he left, the Hayride died. The Hayride was not bigger than Elvis, but the Opry was bigger

than any of its stars.

Bill Anderson (seated) in his deejay days with (from left) Hawkshaw Hawkins; Hawkshaw’s wife, Jean Shepard; Stonewall Jackson;

and Marty Robbins.

BUD WENDELL,

WSM and Opry executive:

Some felt that the Opry was no longer meaningful to artists’ career longevity; that they were wasting their time to go with

it, so there was a lot of turmoil. But the Opry was strong enough to survive and continue, and to be more accommodating and

sensitive to artists’ careers. The Opry had been run in a somewhat autocratic fashion, because it had been the only game in

town: If you wanted to be a star you had to be on the Grand Ole Opry. So we went from that kind of posture to one that was

much more sensitive to the needs of the artists. We had to recognize that there were other, very significant media equally

as significant as the Opry in building a career; and we had to understand that Opry members could make a heckuva lot of money

instead of being there on a Saturday night. It was still an important piece, but it wasn’t the only way to get to the top.

For many years, you could not be a major star without being a member of the Opry. Finally, the Opry woke up and realized that

you could go around the Opry and become a superstar. So it had to kind of change its posture and change its relationships.

Record companies were moving to Nashville, and managers were moving here, publishing companies were moving here, and we were

trying to figure out how to reposition the Opry to keep it strong and make it attractive to artists of some stature to come

in and play and walk away from those big dates.

It wasn’t long before the Nashville music business realized that rock ’n’ roll

hadn’t

killed country music. In fact, rock ’n’ roll had opened up pop airplay to such an extent that a country record could get

played if it didn’t sound too country. In Hank Williams’s day, his songs had to be “covered” by pop artists if they were to

get on the pop charts. It wasn’t long before artists such as Jim Reeves, who’d been an Opry member since 1955, and Patsy Cline

stripped away their Southern accents along with hard country instruments like the steel guitar and fiddle. In came faultless

diction, the piano, vibraphone, electric guitar, chorus, and strings. Just as WSM announcer David Cobb stumbled upon the phrase

“Music City U.S.A.” to describe the industry moving to Nashville, so local magazine owner Char-lie Lamb coined the phrase

“Nashville Sound” to describe the changes that were overtaking country music.