The Grand Ole Opry (22 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

left: The stately Andrew Jackson Hotel turned into party central during the Disc Jockey Conventions.

right: Disc jockeys could make or break an artist’s career, and the annual conventions gave artists the opportunity to make

an impression—in person and with humorous publicity stunts.

Uncle Dave left mementoes to the entire Opry cast, and gave one of his banjos to Roy Acuff’s Dobro player, Bashful Brother

Oswald. The night he died, Hank Williams sang “Farther Along” in his memory. Hank’s tribute to Uncle Dave Macon was only the

second time he’d appeared on the show that year.

Webb Pierce Disc Jockey Convention badge.

LEFTY FRIZZELL,

country star:

[Hank] and me was on the road. I had “Always Late” and “Mom and Dad’s Waltz” and “I Want to Be with You Always” on the charts.

Hank said, “Lefty, what you need is the Grand Ole Opry.” I said, “Hell, I just got a telegram from [music publisher] Hill

& Range on having number one and number two, and I got maybe two more in there, and you say I need the Grand Ole Opry?” He

said, “You got a hell of an argument.”

For years, Hank’s goal had been to reach the Grand Ole Opry, but after less than three years he came to the conclusion that

the Opry needed him more than he needed it. He began to skip the Saturday night Opry and Opry-sponsored shows. The Opry planned

to use Hank’s popularity as leverage to secure a prime-time country music show on NBC-TV, but Hank became increasingly uninterested

in the Opry’s plans for him. His music was also sometimes not in line with the wholesome image of the Opry. When he performed

“My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It” on the show, he had to change “ain’t got no beer” to “ain’t got no milk.” The mutual antagonism

came to a head in August 1952.

ERNEST TUBB:

I came in one Friday to get my mail and I heard Jim Denny on the telephone. He said, “Hank that’s it. You gotta prove to me.

You call me in December, and I’ll let you know about coming back to the Opry next year.” When Jim hung up the telephone, he

had tears in his eyes. He said, “I had to do it. I had to let Hank go.” When I was in the parking lot, I ran into Mr. Craig.

He knew, and he said, “What do you think, Ernest?” I said, “Well, I hate it, but I saw tears in Jim’s eyes, and I know it

was the hardest thing he ever had to do. He told me he was going to try and get Hank to straighten up.” Mr. Craig said, “I’m

sure Jim means well, but it may work the other way. It may kill him.” I was feeling the same way.

JOHNNIE WRIGHT

of Johnnie and Jack, Opry stars:

I was with Hank when he got fired. Jim Denny told him he was going to have to let him go. He had a check coming, about three

hundred dollars. He said, “You cain’t fire me ’cause I already quit.” Jim asked Hank if anyone was there with him, and Hank

said “Johnnie Wright’s here.” He said, “Tell Johnnie I want to talk to him.” I got on the phone and Jim said, “Johnnie, he’s

got a check up here. You come by and pick it up.” My brother-in-law had a Chrysler limousine and Hank had his trailer with

Drifting Cowboys written on the side. We put all his belongings in the trailer and his reclining chair in the back of the

limousine and put him in there. We got Hank in the car and went up to WSM. Roy Acuff was in Jim Denny’s office. Roy said,

“Have you got Hank out there?” I said, “Yeah.” Owen Bradley said, “Let’s go out and see him, Roy.” They went out and I picked

up his check. Then we took off to Montgomery. We went out Broadway, and there was a liquor store out there at 16th and Broad,

and Hank said, “Johnnie, pull in there and get me some whiskey.” So I pulled in and got him a fifth and cashed his three-hundred-dollar

check. The guy that owned the liquor store said, “Is Hank out there?” I said, “Yeah,” so the guy came out and spoke to him.

We took him to his mother’s house. We pulled his clothes off, put him to bed and talked to his mother ’til he woke up. Hank

acted like he didn’t care he’d been canned.

Hank had come to the Opry from the

Louisiana Hayride

in Shreveport, and in August 1952 he returned to the

Hayride,

but just four months later, he was dead. Opry artists played at his funeral, and the show reclaimed him in death.

HORACE LOGAN,

emcee of the

Louisiana Hayride:

Acuff was talking about “Hank’s friends from the Grand Ole Opry . . .” Jim Denny was sat in front of me. He turned around

and said to me, “If Hank could raise up in his coffin, he’d look up toward the stage and say, ‘I told you dumb sons of bitches

I could draw more dead than you could alive.’ ”

Roy Acuff, Red Foley, Carl Smith and Webb Pierce sing at Hank Williams’s funeral.

On January 4, 2003, Hank Williams Jr. and his son, Hank Williams III, performed on the Opry, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary

of Hank Williams’s death. Hank Jr. introduced the son of Rufus Payne, an African American street musician who’d taught Hank

Sr.

Hank Williams wasn’t the only star who conflicted with the Opry’s zealously guarded “family values” ideals. Red Foley’s private

life gave the Opry as much concern as Hank Williams’s no-shows. His wife, Eva, died of a reported heart attack on No-vember

17, 1951, although her death was widely rumored to be suicide brought on by Foley’s infidelities and drinking.

The following April, Foley was sued for one hundred thousand dollars by the husband of singer Sally Sweet, charging alienation

of affection. That same month, Foley made headlines again.

The

Tennessean,

May 1, 1952:

Clyde “Red” Foley, folk singer who was unconscious in Vanderbilt Hospital from an overdose of sedative was described by his

physician as recovering in very good fashion. The physician, Dr. Crawford Adams, said the nationally known Grand Ole Opry

star suffered acute depression with anxiety state resulting from the death of his wife last November and the filing of an

alienation of affection suit against him. It was understood that Foley took a large dose of sleeping tablets at his home on

Bear Road at approximately 9:30 a.m. Monday.

Eva Foley, with Red (left), and their three daughters, including Shirley (third from left), who later eloped with Pat Boone.

He then called someone at Vanderbilt, presumably his physician, and related what he’d done. An ambulance was summoned. The

alienation suit was filed April 16 by Frank B. Kelton, husband of an attractive television singer known professionally as

Sally Sweet, charging that she had been lured and enticed away from him by a certain well-known radio star.

GORDON STOKER

of the Jordanaires, Opry gospel group:

He wanted to do better. He’d quit drinking, join a church, even talk about being a preacher. He really wanted to be a good

Christian, but just didn’t have the inner strength. He once said something that’s become quite a cliché now, but back then

was the first time I’d ever heard it. He said, “I’m my own worst enemy.”

In April 1953, Foley stepped down as host of the Prince Albert Opry, but his behavior grew increasingly erratic. An unpublished

memo in the

Nashville Banner

files from city editor Eddie Jones shows how close to the edge Foley had gone.

Red Foley’s three daughters have left home and have voluntarily placed themselves under full custody of Ernie Newton. Newton

is a bass player on the Opry and apparently a clean straight operator. The story I got was that the children were fed up with

Foley’s new wife, Sally Sweet, and contacted a lawyer and gave him sufficient grounds. Foley is in New York today and due

back in Nashville the middle of next week, after which he says he is going to California to live.

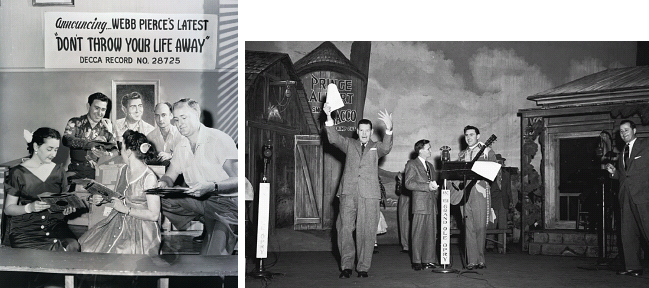

left: Webb Pierce with fans and his manager Hubert Long (right).

right: Webb Pierce on the Opry stage with reporter Charlie Lamb. Announcer Grant Turner encourages the audience to applaud,

while Jack Stapp stands to the right.

left: Marty Robbins.

right: The lore of the Old West always intrigued and inspired Marty Robbins. His father was a Polish immigrant, but he always

identified with his maternal grandfather, who’d been a Texas Ranger.

Hank Williams and Red Foley were gone, but the Opry was still attracting the top up-and-coming stars. Hank had brought Ray

Price onto the show shortly before he left, and Jack Stapp and Jim Denny recruited Webb Pierce, Faron Young, and Johnnie &

Jack from the

Louisiana Hayride,

together with Johnnie’s wife, Kitty Wells.

And out in Phoenix, Harry Stone discovered Marty Robbins and alerted the Opry. Like Jimmy Dickens and George Morgan, Marty

had no hits, in fact no records, but the Opry took Harry Stone’s word and gave him a guest spot on the Prince Albert show

in June 1951. Marty didn’t disappoint, and Opry made him a full member in January 1953. It was hard to get on the Opry without

a hit, but it would never be impossible.

Acquisition of younger singers like Webb Pierce, Marty Robbins, and Ray Price meant that the Grand Ole Opry still had something

for every generation. Singers who would soon revolutionize country and pop music, like Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, and Jerry

Lee Lewis, were listening dutifully every Saturday night. The show was still relentlessly fast-paced and still represented

the pinnacle of the business, but the years immediately ahead would bring fresh challenges.