The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (51 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

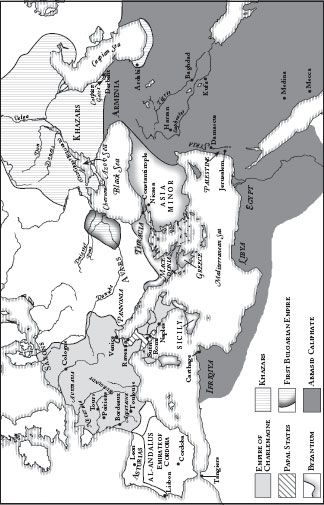

Between 775 and 802, the empress Irene seizes power in Constantinople, while Charlemagne conquers his neighbors for Christ’s kingdom and allows himself to be crowned as emperor

I

N THREE DECADES

on the Byzantine throne, Constantine V had presided over the ongoing quarrels between icon-lovers and icon-haters; he had seen the end of the Umayyad caliphate and the beginning of the Abbasid rule; he had watched Byzantine rule in Italy fail, and Rome finally slip from the grasp of Constantinople; he had heard news of the crowning of Pippin the Younger as the first Carolingian king and the rise of Charlemagne’s power. He had married a Khazar wife and been troubled by the raids of Avars and the invasions of Arab armies.

In 775, the thirty-fourth year of his reign, he began to plan a war against the First Bulgarian Empire.

The Bulgarians had been more or less allies of Byzantium since Tervel and his men had helped Leo III lift the siege of Constantinople, back in 718. But Constantine V’s habit of settling captive peoples (mostly from his battles with the Arabs) in Thracia, crowding the Bulgarian borders, had annoyed the Bulgarian khans.

In retaliation, Bulgarian troops had begun to raid Byzantine land. Constantine V decided that the Bulgarians needed to be put in their place. But in September, as he was preparing to start out on his anti-Bulgarian campaign, he fell ill with what Theophanes describes as an “overpowering inflammation” in his legs that caused severe fever. He died on the fourteenth day of the month, screaming that he was burning alive.

1

For a time, the plan to invade Bulgaria dropped into oblivion. Constantine V was succeeded by his half-Khazar son Leo IV, who abandoned the Bulgarian project in order to secure his throne. He had five half-brothers, the sons of his father’s third marriage, who were threats to his power, and immediately after taking the throne he was forced to exile two of them when he discovered that they were at the center of a conspiracy to remove him from the throne. Then he began to plan an attack against the Arabs in Syria, which he saw as more urgent than the Bulgarian campaign.

2

He never sent his troops into war, though; he died in 780 after only five years on the throne, and his nine-year-old son became the emperor Constantine VI. The little boy’s mother served as his regent. Her name was Irene, like her Khazar mother-in-law, but she was from an old Athenian family.

The youth of the emperor and the regency of a woman in Constantinople struck the new Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi, son of al-Mansur, as a fatal weakness in the empire. He launched a new offensive into Asia Minor and drove the Byzantine defenders away in record time, sweeping all the way to the Bosphorus Strait and setting up a camp at the port city of Chrysopolis, right across the water from Constantinople.

3

This was embarrassing for the regent Irene, who had to pay him an enormous ransom and agree to a yearly tribute in order to get him to withdraw. Perhaps feeling the need for a strong alliance to back her up, in 782 she sent two messengers all the way across to the kingdom of the Franks, and asked Charlemagne to betroth one of his daughters to the eleven-year-old emperor.

Charlemagne could easily think of himself, at this point, as equal in stature to the regent of Constantinople. He controlled the lands of the Franks and Italians, and he was creating a dynasty; he had crowned his third son Pippin

*

as king of Italy, his fourth son Louis the Pious as king of the Frankish territory Aquitaine, and he ruled over them as an emperor rules over vassal kings. His second son, Charles the Younger, had been designated to inherit the job of king of the Franks. Charlemagne had taken on the responsibility of protecting and defining the Papal States (the pope’s land now stretched from Rome in a band across Italy, encompassing Rome, Sutri, and the old Byzantine lands once governed from Ravenna), which made him defender of the Christian faith.

He was the most powerful king in the west, and also the king with the strongest sense of Christian mission in his empire-building. An alliance between the Carolingians and the Byzantine emperors would create not only a united front against the Arabs, but an empire of the spirit: a western mirror for the eastern empire, a Christian counterpart to the ever-advancing Islamic kingdom.

Charlemagne also had plenty of daughters to make useful alliances with (and a lot of sons; in his long life, he had four wives, six additional consorts, and twenty children), and he agreed to marry his third-oldest daughter, Rotrude, to Constantine VI. The little girl was eight years old, so the betrothal took place in name only while both children remained with their parents.

4

Theoretically, the marriage could have become reality when Rotrude reached adolescence—which, in the eighth century, was fairly loosely defined. Certainly when Constantine VI turned sixteen, in 787, he could have asked for the thirteen-year-old Rotrude to be sent to him. But instead, his mother Irene broke off the engagement. Her position was more secure now, and she no longer needed an alliance with the Frankish king. In fact, Charlemagne’s growing power threatened the remaining enclaves of Byzantine-loyal land on the Italian peninsula.

The broken engagement was an insult to Charlemagne, who had been growing not just in power but also in his role as Christian king. The days of the mayor of the palace, reluctant to lay full hold of royal power, were long past. Charlemagne had gathered around him a royal circle of scholars and clerics who were filling in the gaps from his early education (he had received from his father much more military training than book-learning and had never learned to write); they not only discussed with him the finer points of theology, philosophy, and grammar, but also called him “King David,” after the Old Testament monarch who was handpicked by God to lead the chosen people.

*

Under the guidance of his personal tutor Alcuin, a British churchman whom Charlemagne had recruited to teach his sons, the king of the Franks developed a stronger and stronger sense of mission. His conquests were, in his own eyes, forceful evangelism: bringing the Gospel to stubborn unbelievers who needed to be saved not just from their sins but from their own unwillingness to hear.

5

Earlier in the decade, he had concluded a campaign against the Saxons with exactly this sort of persuasion. The Saxon resistance to his rule and the Saxon toll on his army had so angered him that, in 782, he had ordered forty-five hundred Saxon prisoners to be massacred. Their leader Widukind had escaped, but after three years on the run he had finally been forced to surrender. As part of his surrender, Widukind had to agree to Christian baptism; and afterward Charlemagne decreed that any “unbaptized Saxon who conceals himself among his people and refuses to seek baptism, but rather chooses to remain a pagan shall die.” A Saxon who stole from a church, or did violence to a priest, or indulged himself in the old Saxon rites instead of Christian worship, would be put to death. And any Saxon who did not observe Lent properly would be executed.

6

Alcuin objected. “Abate a little of your threatening,” he told the king, “and do not force them by public compulsion until faith has thoroughly grown in their hearts.”

7

Charlemagne considered the argument and agreed, revoking the death penalty. This did not change his sense of duty. He was bringing not merely salvation, but right doctrine and practice, to the western world.

Irene of Byzantium did not see Charlemagne as the king of the Christian west. As far as she was concerned,

she

held the highest God-sanctioned authority in the known world. After she broke Constantine VI’s engagement, she refused to yield the throne to her son even though he was old enough to rule in his own name. She named herself not just regent, but empress; and on that authority, she summoned a church council—the Second Council of Nicaea—to reverse all of the icon-condemning pronouncements made during the reigns of Leo III and his successors.

8

Irene struggled for three years to reign as empress, but too many of the men in Constantinople resented her usurpation, and in 790 the army forced her to hand over authority to Constantine VI. Unfortunately, the rightful emperor turned out to be weak, sadistic, and incompetent. In 791, he set out on the Bulgarian campaign that his grandfather had planned, and was twice defeated by the Bulgarian khan Kardam: “He joined battle without calculation or order,” Theophanes writes, “and was severely defeated. He fled back to the city after losing many men.” The imperial guard, deciding that it had made a mistake, began to plan a revolt that would put Constantine VI’s uncle Nikephorus—one of the half-brothers who had been involved in the conspiracy against Constantine’s own father—on the throne instead.

9

Like his father, Constantine VI discovered the plot. Unlike his father, he did not show mercy by exiling the conspirators. Instead he had all five of his uncles arrested and brought to court. He blinded Nikephorus (who probably had not even been centrally involved in the conspiracy) and, in an act of completely gratuitous cruelty, cut the tongues out of the other four brothers.

Then he blundered back into conflict with the Bulgarians. This time, the khan Kardam threatened to invade Thracia unless Constantine VI paid him tribute. “The Emperor put horse-turds into a towel,” Theophanes writes, “and sent him this message, ‘I have sent you such tribute as is appropriate for you.’” After insulting Kardam, he lost his nerve; when the Bulgarian khan approached at the head of his army, Constantine VI went out to meet him and agreed to send him tribute after all.

10

This was too much for the army, and Irene was able to talk the officials and chief officers at court into a plot against her son. On a June morning in 797, Constantine VI was leaving the Hippodrome after watching a horse race when he saw palace guards approaching him. He knew at once that they were coming to overpower him; he ran through the streets of the city, down to the port, and escaped on board one of his warships. But his companions on board were in the pay of his mother. They brought him back to the city, led him into the palace, and shut him in the imperial chamber where he had been born: the Purple Room, reserved for the lying-in of empresses. “By the will of his mother and her advisors,” Theophanes tells us, “at around the ninth hour he was terribly and incurably blinded with the intention of killing him…. In this way his mother Irene took power.”

11

A

S FAR AS

C

HARLEMAGNE

was concerned, the throne of Constantinople was now empty. Irene was a woman, and she had no legitimate claim to the Byzantine throne. Also Charlemagne, with his passion for correct doctrine, found Irene’s support for icons unacceptable. Although the pope had assured him that icons were not “graven images,” he was not convinced; he even put together a theological committee of his own to study the report of the Second Council of Nicaea and write a rebuttal. (The rebuttal, called the

Libri Carolini

, was sent to Rome, where the pope apparently ignored it.) In his eyes, Irene was not only female and a usurper, but also an idol-worshipper.

12

At the same time, Charlemagne was receiving constant proofs of his own high status among the kingdoms of the west. In 798, the ruler of Asturias, the Christian kingdom in the mountains north of al-Andalus, sent him a formal embassy that requested his recognition for the legitimacy of the king. Since its beginnings in 718 as a tiny and poverty-stricken realm of resistance to Muslim rule, Asturias had grown; the Asturian king Alfonso II now ruled over a realm that included the neighboring city of Leon and the land along the coast all the way down to the city of Lisbon. Alfonso II wanted recognition from Charlemagne, the greatest Christian king of the west, for the legitimacy of his own throne. Charlemagne, never doubting that such an assurance was in his power, gave it.

The following year, he was asked to carry out an even more imperial duty. Pope Leo III, who had occupied the papal throne in Rome since 795, had run into trouble. He was not terribly popular in Rome, either because he was not an aristocrat or because he was immoral and dishonest; no proof for the latter accusations survives, so it is difficult to trace the roots of the enmity. For whatever reason, the hostility swelled in Rome until, in 799, a band of his enemies attacked him in the middle of a sacred procession and tried to cut out his eyes and tongue.

13

Unlike the unfortunate Nikephorus, who had received the same treatment over in Constantinople, Leo III managed to escape with cuts on his face, but with his eyes and tongue intact. He fled to Charlemagne and asked the king to help him drive his enemies from the city.

At Leo’s consecration as pope, Charlemagne had promised to defend him. “My task, assisted by the divine piety, is everywhere to defend the Church of Christ,” he had written to Leo, “abroad, by arms, against pagan incursions and the devastations of such as break faith; at home, by protecting the Church in the spreading of the Catholic faith.” He had not envisioned defending the church at home with arms, which was what Leo needed; and the situation was complicated by the fact that most of his Frankish officials believed that the charges were true.

14