The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (48 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Between 724 and 763, the Khazars convert to Judaism, the clan of the Umayyad loses the caliphate, and the new Abbasid caliphs let go of the west

T

HE CALIPH

Y

AZID

II, who had kept the Umayyad empire from bankruptcy, died after four short years with the frontier lands in turmoil. His brother Hisham took over his post and began to bring iron-handed order to the turbulent empire: sending strike forces into Khorasan and Armenia to fight against the rebelling converts, and sending armies against the northern Khazars as well.

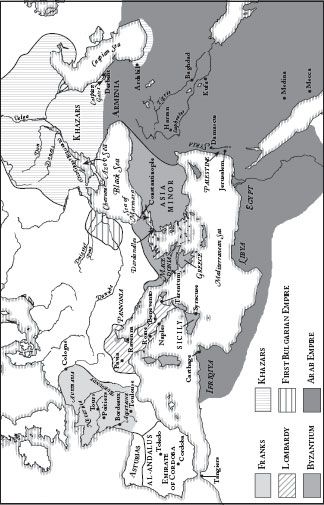

A triangle of power had emerged in the lands east of the Adriatic. The Byzantine emperor occupied one point of the triangle, the caliph another. At the triangle’s tip stood the khan of the Khazars, Khan Bihar. He had been conquering his way steadily into the surrounding lands, and now his realm stretched from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea and far up to the north: a massive empire, one of the largest in the world. The Khazars had taken the city of Ardabil out of Arab hands; the Arabs answered by invading Khazar land along the Volga river; the two armies struggled for control of Derbent, the port city that lay on the Caspian coast right between the two empires.

1

Meanwhile Khan Bihar made a brilliant alliance. In 732, his daughter Tzitzak agreed to be baptized as a Christian, took the name Irene, and married Constantine V of Constantinople.

Despite the alliance, the Khazars treasured their independence—something that was made perfectly clear by the khan’s decision, sometime around the middle of the century, that his people would convert to Judaism. There was no mystery about how the khan discovered Judaism; plenty of Jews had fled into Khazar land during Leo III’s attempts to convert them by force, and Jewish travellers and traders had undoubtedly made their way to Khazar cities long before. But we have to read between the lines to discover his motivations. A tenth-century account remarks that both the Byzantine emperor and the Arab caliph were “incensed” at the khan’s decision to convert, and a letter written slightly later by one of the Jewish kings of the Khazars elaborates:

The king of the Byzantines and the Arabs who had heard of [the khan] sent their envoys and ambassadors with great riches and many great presents to the King as well as some of their wise men with the object of converting him to their own religion. But the King…searched, inquired, and investigated carefully and brought [a priest, a rabbi, and a

qadi

(specialist in Islamic law)] together that they might argue about their respective religions…. They began to dispute with one another without arriving at any results until the King said to the Christian priest: “What do you think? Of the religion of the Jews and the Muslims, which is to be preferred?” The priest answered: “The religion of the Israelites is better than that of the Muslims.” The King then asked the

qadi

: “What do you say? Is the religion of the Israelites, or that of the Christians preferable?” The

qadi

answered: “The religion of the Israelites is preferable.” Upon this the King said: “If this is so, you both have admitted with your own mouths that the religion of the Israelites is better. Wherefore, trusting in the mercies of God and the power of the Almighty, I choose the religion of Israel, that is, the religion of Abraham.”

2

Perhaps more to the point, he did not choose the religion of either of his powerful neighbors; like Dhu Nuwas of Arabia, 250 years earlier, he found a path between.

B

Y

743, H

ISHAM HAD TAMED

the rebellions and invasions in the caliphate. But the victories came at great financial cost; and although Khorasan had been reduced back into order, the order was precarious at best.

3

When Hisham died of diphtheria, the Umayyad caliphate too began to die. He was succeeded by his nephew Walid II, an alcoholic poet who was murdered by his cousin in less than a year; the cousin, Yazid III, lasted for six months and then grew ill. Just before his death, he named his brother Ibrahim to be his heir, but before Ibrahim could consolidate his power, the general Marwan swept down from Armenia with his army behind him, drove out the opposition (Ibrahim, prudently, surrendered and joined Marwan’s men), and in 744 had himself declared caliph, as Marwan II, in the mosque at Damascus. He then moved the capital of the Umayyad caliphate to Harran, closer to his old Armenian territory.

4

He almost succeeded in pulling the empire back together; it had not been under bad leadership for very long, and he had Hisham’s twenty years of order to build on. But Constantine V now took the opportunity to attack. While Marwan was still struggling for internal control, Constantine V invaded Syria and inflicted a serious defeat on the Arab navy in a sea battle in 747.

The defeats fueled the internal opposition to Marwan’s rule. Marwan, like his predecessors, was Umayyad. Since the death of Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali back in 661, the caliphate had stayed within the Banu Umayya, the clan of Muhammad’s old companion Uthman. The Umayyad caliphs had ruled as Arabs over an Arab empire. For nearly a century the strongest glue holding the Islamic conquests together had been Arabic culture: the Arabic language, Arab officials in high positions, a bureaucracy supported by the reimposed head tax on non-Arabs. The worship of Allah was, of course, inextricably entwined with Arabic language and Arabic culture. But the Umayyad caliphs were, in the last analysis, politicians more than prophets, soldiers more than worshippers.

So when political and military fortunes turned against them, their hold on power fragmented. “In the nine decades since the death of Ali,” writes historian Hugh Kennedy, “it had become accepted by many discontented Muslims that the problems of the community would never be solved until the lead was taken by a member of the Holy Family”—a member of Muhammad’s own clan.

5

In the same year as the great naval defeat, Marwan faced both an uprising in Syria and another rebellion in Khorasan. Some of the rebels wanted a descendent of Ali to occupy the caliphate; since Ali’s death, a strong subcurrent within Islam had insisted that only a man of Ali’s blood could properly carry on as his successor (the followers of this current, who also believed that a successor of Ali would be spiritually and supernaturally fitted to rule, were known as Shi’at Ali, the “Party of Ali”). Others, willing to cast their net wider, argued that the caliphate should simply go to a member of Muhammad’s clan, the Banu Hashim: they were known, generally, as Hashimites.

6

The revolt in Khorasan soon spread through the entire province, taking it out of Marwan’s control. In late 749, the Hashimites gathered in Kufa and elected a member of Muhammad’s clan, Abu al-Abbas, as their caliph. Abu al-Abbas could trace his lineage back to Muhammad’s uncle, but his election was not unanimous. The Shi’a rebels had still hoped for a descendent of Ali’s and refused to support him. But even without Shi’a support, Abu al-Abbas was able to gather a sizable rebel army behind him.

Marwan II mustered over a hundred thousand men and marched from his capital of Harran towards Khorasan, meeting Abu al-Abbas and his supporters just east of the Tigris in early 750. The rebel army was fighting for a cause; Marwan’s soldiers were largely unwilling recruits, and the Umayyad force was driven back and then scattered. Marwan himself was forced to flee. He went first into Syria and then south into Palestine, and then farther south into Egypt, attempting to raise another fighting force.

Meanwhile Abu al-Abbas sent out scores of men on horseback, their mission to find and kill the remaining Umayyads. Hisham’s grandson and the heir apparent to the caliphate, the twenty-year-old Abd ar-Rahman, was living in Damascus with his family. When word of the defeat reached him, he fled eastward with his brother and a Greek servant, apparently hoping to hide in some small unremarkable village in the old Persian lands. Al-Abbas’s men caught them on the banks of the Euphrates; Abd ar-Rahman flung himself into the water and began to swim, but his brother hesitated. The soldiers of al-Abbas beheaded him on the spot and left his body unburied on the shore.

7

But Abd ar-Rahman made it to the opposite shore, as did his Greek servant. The two men kept on the move. Apparently they changed course, because they soon arrived in Egypt and then traveled on west through Ifriqiya; Egypt was not safe. Marwan, in Egypt trying to find an army, was caught sleeping in an Egyptian church in August. Deserted by most of his followers, he threw himself against the band of Abbasid soldiers and was murdered in front of the door. His head was sent back to al-Abbas, who by this time had earned the nickname

al-Saffah

, “The Slaughterer.”

8

Al-Abbas, ruling from Kufa as the new center of his caliphate, did his share to make the new Abbasid caliphate secure. He promised that all remaining members of the Umayyad family would be granted amnesty and given back their family property if they would come and swear allegiance to him. A contemporary chronicler tells us what happened: ninety unwary men and women showed up and were seated at a welcome banquet, but before they could eat, al-Abbas’s guards surrounded the banquet hall and killed every single one.

9

T

HE NEW

A

BBASID CALIPH

had to deal with attacks on both the far east and far west of his land.

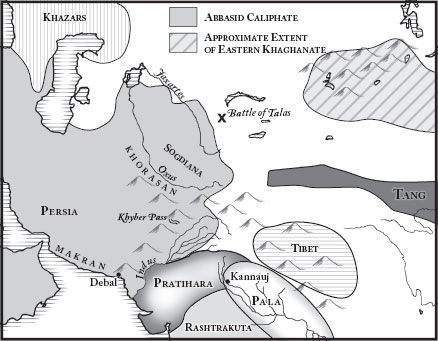

The first threat came from the east. For some years, the Tang general Gao Xianzhi, serving the Brilliant Emperor Tang Xuanzong, had been leading a slow progression across the Asian plateau, pushing his way almost all the way to the eastern reaches of the Islamic empire in Sogdiana, just east of the Oxus river. The Umayyad caliphs, increasingly weak and disorganized, had not been able to halt this advance. Now an Abbasid army of a hundred thousand men marched eastward to meet the threat.

Gao Xianzhi had travelled light and far, and his force of thirty thousand was no match for the opposition. At the Battle of Talas in 751, the Abbasids defeated the Tang force, ending the Tang attempt to take control of central Asia. Gao’s forces were nearly wiped out, only a few thousand left alive. Without enough men to launch a counterattack, Gao Xianzhi turned for home.

“The Slaughterer” died in 754, and his brother al-Mansur succeeded him as caliph. Al-Abbas had ruled from Kufa, but al-Mansur moved the capital to the village of Baghdad. It was a strategic location to build the empire’s wealth: “Here’s the Tigris, with nothing between us and China, and on it arrives all that the sea can bring,” he told his officers, “and there is the Euphrates on which can arrive everything from Syria and the surrounding areas.” He began to build, transforming the tiny town into an imperial capital.

10

48.1: The Battle of Talas

The move suggests a new eastward focus, and when another problem arose on the western edge of the caliphate, al-Mansur did not try very hard to solve it. In 756, the fugitive Umayyad heir Abd ar-Rahman had arrived in al-Andalus. He had made his way, over six long years, across North Africa to the edges of the last Umayyad province left in the Muslim world.

He sent a message to the Umayyad governor of al-Andalus, Yusuf al-Fihri, announcing that he had arrived to claim al-Andalus as his rightful territory. The message was not greeted with joy. After the Abbasids had seized power, Yusuf al-Fihri had gone right on governing as an independent Umayyad ruler. He was not pleased to discover that a man with a better claim to al-Andalus had appeared on the horizon, and he declined to hand the land over to Abd ar-Rahman.

The two men met in battle just outside Cordoba. Abd ar-Rahman was victorious; he defeated and beheaded Yusef al-Fihri and became the de facto caliph of al-Andalus. But he did not yet claim the title of caliph. Instead, he took the lesser title of “Emir of Cordoba”: prince, not king, but still the ruler of the first Muslim kingdom to be entirely independent of the caliphate.