The Incredible Human Journey (44 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

‘But I think it’s a long, drawn-out process [across Europe]; there’s not one event that causes their extinction.’

In contrast to the traditional view of Neanderthals as cold-adapted people of Ice Age Europe, Clive Finlayson viewed them

as warm-loving humans, who survived late in Gibraltar because Mediterranean conditions lasted longer there. Even in winter,

days were long, and the range of environments around the coast of Gibraltar allowed people with a diversified subsistence

to survive in rough times – at least until the Heinrich 2 Event. In contrast, Clive saw the

modern humans

as the more cold-adapted bunch of people. He may be right. Although Neanderthals are stocky and short-limbed – suggesting

they were biologically better adapted to cold climates than rangy, long-limbed modern humans, they may not have had the cultural

adaptations to beat the chill of the Ice Age. And their physical adaptations may even have held them back. Contrastingly,

if modern humans were physiologically more vulnerable to cold, this may have spurred them on to develop advanced clothing

– which later meant that they had the wherewithal to survive through the LGM.

7

Certainly, at around 25,000 years ago, we see a new culture emerging in Europe, apparently brought in by a second wave of

modern humans from the north-east: people who appeared to have been quite comfortable in temperatures that are more reminiscent

of Siberia today.

A Cultural Revolution: Dolní Vìstonice, Czech Republic

The period between 30,000 and 20,000 years ago was one of global climatic instability, leading up to the LGM.

1

During this time, a new culture and technology spread across Europe – the Gravettian, named after the site of La Gravette

in the Dordogne, where the characteristic stone points of this technology were first recognised.

This culture appears to have started in north-eastern Europe about 33,000 years ago, with sites like Kostenki, on the Don

River. It comes along as the world was cooling down, in the run-up to the peak of the last Ice Age, and many archaeologists

see the Gravettian as an adaptation to colder, periglacial environments. Perhaps not surprisingly, then, although this culture

is a European phenomenon, there are similarities with the middle Upper Palaeolithic culture of Siberia. The Gravettian is

the ‘technology of the steppes’: these people were reindeer and mammoth hunters, who thrived in cold climates, and spread

into Europe as the temperature dropped off.

Innovations in the Gravettian include better shelters – such as the 25,000-year-old semi-subterranean dwelling at Gagarino

on the Don. The hearth in this Ice Age house contained burnt bone: it appears that the Gravettians were turning to alternative sources

of fuel. Stone lamps appear in the archaeological record, and, at Kostenki, lamps seem to have been made from the heads of

mammoth thigh bones. Just as in Siberia at this time, eyed needles indicate that people were capable of making clothes. The Gravettians also seem to have invented cold storage – digging pits (using mammoth-tusk mattocks) which may have been used

to store meat or bones for fuel. The hunting technology of the Gravettians included a range of innovations: bevelled stone

points, ivory boomerangs and even woven nets – perhaps for hunting small game. Compared with the Aurignacian, stone blades

were narrower and lighter, often retouched into very sharp points. Some assemblages include tanged or shouldered points.

2

There also appear to have been changes in society. Massive, complex occupation sites have been found that suggest people were

‘getting together’ on a large scale. Whether these are gatherings for communal hunts, feasts or other social occasions is

unclear, but this certainly implies that social networks were enlarging and society was getting more complex for these Ice

Age hunter-gatherers. 3 Perhaps the most intriguing material evidence passed down to us from the Gravettian, though, are objects

that have no obvious function: the so-called ‘Venus figurines’.

I headed to the Czech Republic, taking the train to Brno, then heading south to the small town of Dolní Vìstonice (pronounced

‘dolny vyestonitseh’), close to where one of these mysterious female figures was found. There I met up with Jiri (pronounced

‘Yurjy’) Svoboda at the museum in Dolní Vìstonice. Upstairs in the museum, he brought out shallow boxes full of the finds

from the archaeological site. There were numerous animals carved from mammoth ivory, including a tiny, beautifully observed

head of a lion. There were also strange bone spatulas, about the length and shape of shoehorns, but flat.

‘What on earth’, I asked Jiri, ‘are these?’

‘If you go to ethnography, you can find a whole variety of uses for pieces like that. You might use it for cutting snow, for

example. Eskimos have tools like that. But I have also seen a similar tool in Tierra del Fuego for taking bark from trees.

And the Maoris of New Zealand have similar pieces as prestigious, symbolic weapons. Unfortunately it’s very difficult to

find any use-wear on the edges, so we can only guess.’

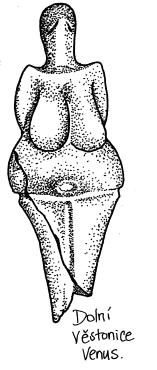

And then Jiri brought out the Dolní Vìstonice ‘Venus’. She was a strange little figure, just over 10cm tall, made from fired

clay. She was very stylised, with an odd, almost neckless head; the face was a mere suggestion, with two slanting grooves

for ‘eyes’. She had globular, pendulous breasts, and wide hips. Her legs were separated by a groove, and another groove ran

around her hips, as though indicating some kind of girdle. On her back, pairs of diagonal grooves marked out her lower ribs.

Compared with the stick-thin and often clothed female figurines I had seen in the Hermitage, from the Siberian site of Mal’ta,

this ‘Venus’ was more rounded and buxom, and splendidly naked.

I asked Jiri what he thought she represented. He was cautious: the real meaning of these mysterious prehistoric objects is

lost, and we can really only guess what they symbolised. Was she a deity? Did she represent some kind of archetypal female,

or did she perhaps combine male and female sexuality in one? Jiri covered up her upper half, and the legs of the figurine,

with that deep groove between them, could certainly be taken to represent a vulva. Then he covered up the legs, and her head

and breasts were transformed into male genitalia.

‘So perhaps she is a combination of the two symbols: male and female.’

‘Do you think she could be a deity, a goddess?’ I asked.

Jiri laughed. ‘Well, maybe a deity. But it depends on how you define that. I think there is some kind of personification,

some symbolism here, that is depicted in the shape of a female body. There is certainly some meaning, but it’s very difficult to know exactly what.’

There were other objects in the collection from Dolní Vìstonice that seemed to represent sexuality in some way, including

a small ivory stick with a pair of protruding bulges – which could be seen as breasts or testicles. Jiri certainly saw some

connection between the archaeological signs of widening social networks and the development of symbolism represented by objects

like the ‘Venus’.

1

Whatever the Dolní Vìstonice ‘Venus’ meant to the society who made her, she was special in another way – because she was made

of clay. She is among the first ceramic objects in the world – and one of some 10,000 pieces from Dolní Vìstonice and the

nearby site of Pavlov. At 26,000 years old, these ceramic objects pre-date any evidence of utilitarian pottery, i.e. ceramic containers, by some

14,000 years.

4

Many of the fired clay pieces were just irregular pellets, but among them were works of art – more than seventy, nearly complete,

clay animals, and the Venus figurine. But there were also thousands of fragments of figurines, many of which had been found

in what seemed to be purpose-built kilns up the hill from the occupation area. Analysis of the kilns suggested that they produced

temperatures of up to 700 degrees C. The preponderance of ceramic fragments has led some archaeologists to formulate a rather

bizarre theory: that the figurine-makers were pyromaniacs, deliberately exploding their creations in kilns – and the smashed

figurines were the relics of a strange prehistoric form of performance art. Pottery specialists argued that the pattern of

breaks in the clay fragments was commensurate with heat-fracturing, but I remain quite sceptical about the deliberate explosion

theory. We were looking at the earliest ceramics in the world – presumably there was a fair amount of experimenting going

on – so was it really that surprising that many of the pottery creations had exploded? And it seems reasonable to imagine that successfully fired figurines would have been removed from the kilns, while leaving

behind fragments of exploded pieces. Not only that, but the exploded fragments could feasibly have been incorporated into

the structure of the kilns; this is something that has been seen, admittedly thousands and thousands of years later, in clay

pipe kilns, where broken pipes are included in the kiln.

5

Dolní Vìstonice is also famous for a strange burial, where three individuals were placed in the ground at the same time. There

were two male skeletons on either side of a skeleton whose sex was difficult to determine, but which was definitely pathological.

The skeletons lay in unusual positions – the individual on the left lay with his arms stretched down and out towards the

person in the middle, his hands lying over the pelvis of his grave mate, while the male skeleton on the right was buried face-down.

Red ochre covered the heads of all three, as well as the pubic area of the middle skeleton. Wolf and fox canines and ivory

beads were found around the heads of the three skeletons.

6

It seems that these three individuals were indeed buried together, at the same time, and this in itself is very unusual. It

is possible that they were related: certainly, they shared unusual anatomical traits, including absence of the right frontal

sinus (the space in the skull bone above the eyes), and impacted wisdom teeth.

7

But why did they end up in the same grave? They are all quite young: one was a teenager, the other two were in their early

twenties. Some archaeologists have suggested their youth indicates a particular adverse circumstance befalling the Gravettian

population of Dolní Vìstonice, but, from the other human remains at the site, death in early adulthood does not seem to have

been particularly unusual.

8

The deformed leg bones and spine of the middle skeleton have been variously ascribed to rickets, paralysis or congenital anomalies,

but it is difficult to be certain about what caused the bony abnormalities in this individual. Although only in their early

twenties, he (or she) had already developed osteoarthritis in the right shoulder. Despite the fact that this individual was

young when he or she died, there is no indication that the deformities caused this person’s death. What is certain, though,

is that this individual would have had a very obvious pathology; some archaeologists have argued that this could have been

part of the reason that he (or she) was accorded respect, and selected for what seems to have been a special burial.

6

There are certainly unique things about the Dolní Vìstonice burial – but there also aspects of it, in particular the use of

ochre and the ivory ornaments, that indicate it was part of a culture that stretched across Europe – and I mean

right

across Europe – in the Gravettian. Around the same time as the Dolní Vìstonice burial – about 27,000 years ago – a man was buried at Paviland Cave on the Gower

in South Wales, with ochre and ivory rods in his grave. And at Sunghir, some 200km north-east of Moscow, about 24,000 years

ago, a man and two children were buried along with ochre, fox pendants and thousands of ivory beads, apparently sewn on to

clothing.

9

Jiri Svoboda and I left the museum and drove up the road to the archaeological site of Dolní Vìstonice – which was now, like

most of undulating lower slopes of the Pavlov Hills, covered in grapevines. We climbed the hill to the top of the vineyard,

where Jiri pointed out the locations of the two main sites, on slightly raised ridges perpendicular to the slope.

‘To our left is the first site that was excavated in this area, in the twenties,’ Jiri explained. ‘There was a priest going

to Dolní Vìstonice church, from Pavlov, and he noticed, in the cut of the road, bones and charcoal coming out. When it was

excavated, that is where the Venus and the other clay figurines were found.’

The second site had been discovered during commercial quarrying in the mid-eighties.

10

Jiri pointed along the ridges to our right. ‘The triple burial was on the next one – at the site of Dolní Vìstonice 2. It

looks like people may have been burying their dead in the settlement, inside a hut. And probably other people didn’t go in

any more, and the hut collapsed, and that would be the burial.’

Jiri explained that Dolní Vìstonice was just one of a series of settlements along this escarpment, and he also placed it in

its wider geographical – and chronological – context. Where we were standing, on that hillside in Moravia, formed part of

a corridor that also led through southern Poland and lower Austria, a low-lying passage between the Carpathian Mountains in

the east and the Bohemian Massif in the west. It allowed fauna – including humans – to move from south-west to north-east

on the European plain.