The Incredible Human Journey (45 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

At the end of the Pleistocene, between 30,000 and 20,000 years ago, the Moravian landscape would at times have been partly

wooded, mainly with conifers, but also with oak, beech and yew. These species make it sound as if the climate was rather

more pleasant than it actually was; even when there were trees around, snails indicate very cold temperatures, more like subarctic

tundra. The climate was fluctuating, and there were even colder, drier periods when the landscape would have been transformed

into a treeless steppe.

1

‘It’s difficult to find a present-day analogy,’ said Jiri. ‘Siberia has a zonality of its own today – it’s different in the

south and the north – but it’s possible to imagine what it would have been like here. Mean annual temperatures were very low. But although the winters were much colder than today, some of the summers could have

been quite hot.’

Whereas Aurignacian sites often occupied higher ground, the Gravettian sites of Austria, Moravia and southern Poland are clustered

along the mid-slopes of river valleys. The hilltops would have been too cold. The large mammals hunted by the Gravettians

would have passed through the valleys, and so the camps were well positioned to intercept the herds.

1

‘We can imagine a forested landscape below, and the slopes covered by steppe, but again with some conifers. The sites control

the valley, and the game was in that valley. This is the place where we can imagine mammoth herds.’

These Gravettian sites seemed to represent more than just temporary hunting camps: they appear to have been occupied through

the year. The intensity of the occupation layers, the richness of artefacts – including things which were both delicate and

time-consuming to make, the stability of the house structures – all point to a less nomadic and more sedentary existence.

‘These big sites were almost long-term settlements,’ explained Jiri, as we stood looking down over the vineyard and the gently

rolling ridges. ‘But at the same time people were quite mobile. So probably they combined the two: some people stayed at the

campsite – here – and others went off to find raw materials and to hunt.’

It reminded me of the Evenki, with their villages and satellite hunting camps.

‘It always depends on local conditions,’ said Jiri. ‘Because normally, of course, hunter-gatherers are mobile people, but

there were time periods and specific environments and strategies that enabled more sedentary ways of life.’

The new culture that swept across Europe seems indeed to have been a movement of people and genes – and not just ideas (see

map on page 207). Analysis of European mtDNA has revealed two lineages: the haplogroup H (the most common in Europe) and pre-V,

which appear to have originated in the east, around the Caucasus Mountains, between the Black and the Caspian seas, and spread

across Europe between 30,000 and 20,000 years ago.

11

,

12

,

13

But just as this second wave of Europeans spread from east to west, Europe was becoming colder. As the LGM approached and

the ice sheets descended, northern Europe – as well as northern Siberia – was all but abandoned. Even the cold-adapted, fur-clad,

reindeer-hunting Gravettians couldn’t survive in those truly Arctic conditions. Archaeology and genetics – European mtDNA

and Y chromosome lineages – record the contraction of the population into refugia in the south-west corner of Europe.

Sheltering from the Cold: Abri Castanet, France

So it was that I made my way to south-west Europe – to the Périgord region, practically synonymous with the Dordogne

département

, whose caves and rockshelters contain an incredible record of Ice Age life.

Heading north from Toulouse, I drove through up through wooded gorges so typical of the Dordogne, where the large rivers running

west from the Massif Central to the Atlantic have etched the limestone bedrock. I eventually hit the Vézère Valley and followed

it west, reaching the town of Les Eyzies, famous for its many rockshelters. The valley was wide and plunging, framed by limestone

cliffs which were incised with a deep, horizontal groove. These grooves in the cliffs – high enough to stand up in – were

used as rockshelters by modern humans, or, as these ancestors are known in France, in honour of the first fossil found, Cro-Magnon

man.

I continued along the Vézère Valley, through the small hamlet of Le Moustier – famous as the place where Mousterian tools

were first discovered, though in my journey I had now left the Neanderthals behind. Turning off the main river valley and following a road leading up one of its tributaries, through the village of Sergeac,

and into a narrow wooded valley, the Vallon de Castel-Merle, I eventually reached the site of Abri (rockshelter) Castanet.

As I pulled up, American archaeologist Randall White emerged to greet me.

‘When does the occupation here date to?’ I asked him.

‘We have good radiocarbon dates of 33,000 years ago,’ Randall replied.

As an early Aurignacian site, Abri Castanet represents evidence of that first wave of modern human colonisers into western

France. At that time, during the Würm interstadial of 40,000 to 30,000 years ago, the climate would certainly have been cold,

though not fully glacial.

1

During early Aurignacian times, the valleys of the Vézère and its tributaries would have been covered in grassy steppe, with

woodland on south-facing slopes and in sheltered valleys.

‘We know the people were living here at Castanet in mid-winter,’ said Randall, ‘when it was probably about 35 degrees below

zero outside.’

That sounded cold enough – almost as cold as it had been in Olenek – but Randall thought that people would have been able

to keep warm in the deep rockshelters.

‘There are holes in the rock where we think they were running lines to drop animal skins down to close off the interior space,’

explained Randall. ‘And then are fireplaces inside. I think they’re making their world a fairly comfortable place.’

A team of American students were busy trowelling away in the rockshelter. They had come down into the Ice Age floor surface,

where, among natural stones pressed into the ground, there were stone tools and flakes lying around. There was a dense black

layer in one part of the rockshelter – the remains of an ancient hearth. As sediment was excavated, it was bagged up and carefully

wet-sieved. The sievings were retained and dried, then Randall and his team painstakingly picked through the material, looking

for minute fragments of flint and bone. There were clues here as to how the Aurignacians had survived the long, hard winters.

‘The bottoms of our sieves are absolutely full of burned animal bone. A large percentage of the animal bone they’re bringing in from hunting is being consumed as fuel,’ explained Randall. But

bone fires would not have been straightforward. ‘Bone is a terribly difficult thing to burn. There’s relatively little wood charcoal here, but they seem to be adding wood to bone fires to keep the temperature above

a certain threshold. It must have been a constant focus of their attention, keeping these fires going. They’re collecting

dung for fuel as well. We take fire and heat for granted, but I don’t think they did at all.

‘This was a very diverse environment,’ Randall told me. ‘Reindeer dominate at Castanet, but we have the remains of nine large

herbivore species as well as a lot of birds and some fish. This was a pretty good environment for hunters and gatherers, even

though it was cold.’

The fauna roaming this landscape would have included reindeer, horse, bison, ibex, as well as animals more suited to forest

environments, like boar, roe and red deer.

2

Excavations at Abri Castanet had also turned up hundreds of stone beads. Most of the beads from Castanet were quite tiny,

the majority less than half a centimetre across. They were shaped like tiny baskets, and had been carved out of soapstone.

Without wet-sieving of the sediments from the rockshelter, to wash out the dirt from the holes in the beads, they would just

have looked like tiny stones and could easily have been disregarded.

‘It’s interesting to imagine people here, in winter, making all these thousands of beads. Probably done around these fireplaces,

like the way we do embroidery or knitting, like a craft. It occupied time on those long nights,’ mused Randall.

Like Nick Conard, Randall White was interested in what we could learn about Ice Age society from its art and ornaments – in

fact, particularly from personal ornaments, which he believed were much more than just trinkets: to him they were important

representations of belief, values and social identity.

3

While many facets of personal adornment – clothing, body painting and organic ornaments – don’t usually survive in the archaeological

record, those little stone beads had stood the test of time at Abri Castanet.

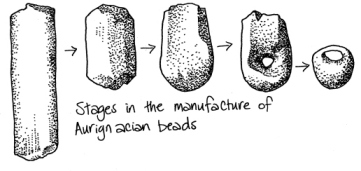

Randall and his team had discovered beads in various stages of manufacture, so it had been possible to work out how the beads

had been made: starting with a rod of stone, which was then scratched round and round until a bead blank could be snapped

off. The blank would be thinned and flattened at one end, then pierced by gouging on both sides, and finally trimmed down

into the classic basket shape. Although made of soapstone, the method – of taking a baton and dividing it into blanks, then

gouging out perforations – was similar to that in German Aurignacian sites, like Geissenklösterle, where ivory beads had been

made.

4

,

3

The beads had also been polished to a high lustre. Thousands of years before metals were discovered, these people were

clearly after the same qualities we enjoy in jewellery today.

There are no burials from the Aurignacian (did they bury their dead at all, or perhaps leave them out – like the Siberian

sky burials?) so it is difficult for archaeologists to determine how these beads were used. However, experimental work with beads combined

with electron microscopy suggests that the Aurignacian basket beads were sewn on to something – presumably clothing.

4

But why was Randall so fascinated by Stone Age beads?

‘Twenty years ago everybody laughed at me when I started working on beads. But it’s about what beads

say

about the societies that these people were making for themselves. The moment you can begin to construct identities by ornamenting yourself differently,

by clothing yourself differently, you can provide a more complicated and effective organisation within a group, but you can

also create identities across landscapes,’ he explained. ‘It may well be that the people in the Basque country felt themselves

to be part of the same cultural entity as the people here in France – it’s a very large area. Not many people would say that

Neanderthals had those sorts of societies. I think the ability to organise large numbers of people across large territories

would have been an enormous advantage, and I personally think that’s part of the reason why Neanderthals wilted away.’

As the Last Glacial Maximum approached, northern Europe became virtually uninhabited, with ice sheets and permafrost blighting

the ground. But in south-west Europe, modern humans clung on. The seasons there were moderated – as they are today – by proximity to the Atlantic: summers were cooler and, more significantly, winters were warmer than in central Europe. But although Iberia and southern France were south of the permafrost zone,

the ground was still often frozen. In the Vézère Valley, the frozen uplands would have become uninhabitable, but the protected

valleys still supported the hunters of the steppe. The Vallon de Castel-Merle and other valleys were not abandoned. It seemed remarkable.

But despite these harsh climatic conditions, the steppe-tundra grasslands of south-west Europe were fairly teeming with game.

Mellars describes south-western France as being almost like a ‘last-glacial Serengeti game reserve’.

5

Reindeer, horse and bison – all migratory, herd animals – remained common in southern France, along with ibex, chamois, red

and roe deer, saiga antelope, and the occasional mammoth and woolly rhino.

6

But perhaps this makes it sound too idyllic … ‘At the Last Glacial Maximum, the reindeer here reduce in size. Even for reindeer

this was an incredibly cold environment: even the animals were stressed,’ explained Randall. ‘I know that when I was growing

up in Canada, we had some winters in which we had five or six weeks when the temperature never got above zero. It starts to

act on your head. I can’t imagine what it must have been like spending three months in a rockshelter in those kinds of conditions.’

Those hunters were under considerable stress, but, necessity being the mother of invention, they changed their subsistence

patterns and broadened their food base: they were still hunting large animals like horse, reindeer and red deer, but there

was an increasing reliance on smaller mammals, fish and birds. This intensified subsistence was accompanied by a change

in technology: the hunters started to make finely chipped points with concave bases, characterising a whole new industry,

called the Solutrean.

1

,

7