The Knight in History (8 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

The slaughter that followed was reported in every contemporary chronicle, western European, Greek, Jewish, and Muslim. Raymond d’Aguilers wrote that dismembered bodies lay in the houses and streets, trampled by knights and men-at-arms, and exaggerated that “in the Temple of Solomon…Crusaders rode in blood to the knees and bridles of their horses.”

80

According to Fulcher, “They did not spare the women and children.”

81

Writing a century later, Archbishop William of Tyre declared that “the victors themselves were struck with horror and disgust,”

82

but contemporary writers record no such reaction. Rather, they excused the slaughter as “poetic justice [for] pagans who blasphemed God” (Raymond d’Aguilers).

83

Many other instances of shocking brutality on the part of the Crusaders are recorded: the mutilation of Slav prisoners,

84

the slaughter of captives at Antioch and Albara, the torture of “hapless Muslims” at Ma’arrat al-Nu’man,

85

the mounting of heads on posts

86

or even use of them as missiles,

87

and the dismemberment of bodies in search for swallowed gold pieces.

88

The chroniclers notwithstanding, the barbarous behavior of the Crusading knights was not inspired wholly by the fact that the enemy were pagans. Massacre and torture were common enough in warfare in Europe and continued to be in the centuries to come. Brutality was an inescapable aspect of medieval soldiering, for knights as for others.

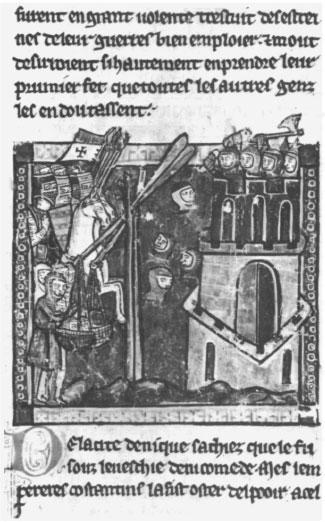

CRUSADERS BOMBARD NICAEA WITH HEADS OF DEAD ENEMIES. (LES HISTOIRES D’OUTREMER,

BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE, MS. FR. 2630, F. 22V

)

Whatever the relationship of religious fanaticism to the savagery, it did not repress the knightly proclivity for turning war into sport. At Antioch, Raymond extolled “the bravado of the army whose knights actually sang warlike songs so joyously that they seemed to look upon the approaching battle as if it were a sport.”

89

Before the battle with Kerbogha, the Crusading leaders proposed to the Turks that the issue be settled by a combat between picked companies from each side, but the Turks refused.

90

Though the prospect of acquiring land had been held out to the knights and though during the expedition many were apparently planning on settlement (they “got out of bed at midnight,” says a chronicler, to seize villas in the plains of the Jordan),

91

only a handful actually stayed in the Holy Land. Even these remained for the most part not as settlers or landlords but as garrison soldiers. While a few of the Crusade’s leaders—Godfrey of Bouillon, Bohemund and Tancred d’Hauteville, Baldwin of Boulogne—assumed titles of royalty and for a time lorded it over subject populations, nearly all the knights who had survived the fighting and the rigors of the expedition returned home. This was in marked contrast to the members of the other two major military expeditions of the time, the Norman conquests of England and Sicily. Syria and Palestine apparently had little appeal as permanent homes for the men of Europe.

The history of the later Crusades is essentially that of efforts to sustain and reinforce the garrisons left behind, a history in which a major role was played by the Military Orders: the Templars, the Hospitalers, and the Teutonic Knights, whose story will be told in another chapter.

Modern historians have pronounced a generally negative verdict on the Crusades. The cultural osmosis between Islam and the West, once credited to the Crusades, is now perceived as taking place mainly through other points of contact, chiefly in Italy, Sicily, and Spain. Viewed strictly from the perspective of the knightly class, however, the great adventure had profound and beneficial effects (whatever the fates of individual Crusaders). It provided a needed safety valve for surplus sons, such as the two Hongres who went on the First Crusade and the grandson of Humbert Le Hongre who perished on the Second. Crusading broadened the horizons of the rustic knight whose world had consisted of the village, the neighboring castle, and an occasional

chevauchée

or pilgrimage. Not only was he exposed to new scenes and ideas, but he mixed with knights and lords of other regions of France and of Europe. In the later Crusades he even met kings and emperors. This mingling of the European elite helped to counteract the feudal political fragmentation and was a factor in the development of national feeling. At the same time, the knights acquired a taste for travel and for luxury that enriched their life-style.

Most important, the Crusades, and above all the First Crusade, gave an immense impetus to the Christianization of knighthood, the idea of chivalry that had been fostered by the Peace of God and the Truce of God. One who had fought in the Holy Land wore the imaginary badge of the

militia Christi

, Christ’s soldiery, in the eyes of the twelfth century surely the insignia of true knighthood.

The Troubadours and the Literature of Knighthood

“…

THE ONE I DESIGNATE WITH MY FINGER—” POINTING TO A SPIRIT IN FRONT—“WAS A BETTER CRAFTSMAN OF THE MOTHER TONGUE. IN THE POETRY OF LOVE AND PROSE OF ROMANCES HE SURPASSED THEM ALL

.”

—Dante,

Purgatorio

FIRST OF ALL, ARNAUT DANIEL, GREAT MASTER OF LOVE, WHO IN HIS OWN LAND STILL DOES HONOR WITH HIS STRANGE AND LOVELY SONG

.

—Petrarch,

Trionfi

I

F THE event of the eleventh century that had the greatest impact on the knight was the First Crusade, the most important influence of the twelfth century on the knightly class lay in a totally different direction: the outpouring of chivalric literature, above all, that of troubadour poetry. The troubadours were knights, as were their successors, the trouvères of northern France and the minnesingers of Germany. Their verses demonstrate an inventiveness and sophistication that is startling after the simplicity and rough piety of the chroniclers of the First Crusade. Living amid the civilized court and castle life of southern France, these knight-poets reached the height of their fame three generations after the Crusade, toward the end of the “Renaissance of the twelfth century,” with its great achievements in scholarship, law, science, philosophy, and historical writing.

Unlike the individually obscure Crusading warriors, the knightly troubadours left lasting records of their personalities in their verses, and in many cases considerably more is known of them. Arnaut Daniel, celebrated by Dante and Petrarch and translated by (among others) Ezra Pound, is one of those troubadours to have a

vida

, or biographical sketch, appended to the thirteenth-century manuscript of his poems.

“Arnaut Daniel was from the same region as Arnaut de Mareuil [another troubadour], from the bishopric of Périgord, from a castle called Ribérac, and he was a gentleman. He was accomplished in letters and loved to write songs. He abandoned his learning and became a jongleur, and adopted a fashion of composing in precious rhymes

(caras rimas)

, so that his songs were not easy to understand or learn. And he loved a noble lady of Gascony, wife of Lord Guillem de Buovilla, but the lady did not grant him the pleasure of love; so that he said:

‘I am Arnaut who gathers the wind

And hunts the hare with the ox

And swims against the incoming tide.’ ”

1

INITIAL FROM A MANUSCRIPT OF ARNAUT DANIEL’S POEMS SHOWS HIM IN A SCHOLAR’S CAP AND GOWN.

(BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE, MS. FR. 854, F. 65)

The castle of Ribérac (now demolished) stood on the banks of the river Dronne, fifty miles northwest of Bordeaux. Built by the counts of Périgord (the Talleyrands) in the tenth century, it was the seat of a viscount. We do not know Arnaut Daniel’s status in the castle, but the designation

gentils bom

shows that he was a son of a knight, possibly a lord. His accomplishment in “letters” suggests that he was a younger son intended for the clergy. Another troubadour described him as “Arnaut the scholar who is ruined by dice and backgammon, and goes about like a penitent, poor in clothes and money.”

2

He seems to have been a friend of troubadour-knight Bertran de Born (fl. 1175–1196), to whom he addressed a poem.

3

From his verses, we may conjecture that he attended the coronation of the French king Philip II in May 1180,

4

the beginning of his period of productivity, which lasted until 1210. A story, probably apocryphal, that accompanies his

vida

says that he participated in a poetic competition at the court of Richard Lionheart.

5

Such is the surviving information about the poet who “surpassed them all.”

6

The estimate of many modern critics agrees with that of Dante and Petrarch, that he was the most gifted of the host of knightly poets who enriched Western literature with their outpouring of “Provençal” poetry in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, stimulating similar literary movements in northern France, Spain, Germany, and Italy and permanently influencing the literary tradition of Europe.

Two elements distinguished the new poetry: it was written not in Latin but in the vernacular, the “mother tongue,” and its customary subject matter was romantic love. Love was hardly a new theme for poets, but the Romans treated it realistically (Catullus), heroically (Vergil), or satirically (Horatius and Propertius). The Latin poetry of the early Middle Ages usually dealt with more serious philosophical or religious subjects; when a lady was praised, it was as a patroness. Romantic love introduced a new theme, one that idealized both the love object and the emotion experienced by the lover.

7

The troubadours are usually referred to as “Provençal poets,” but the term is slightly misleading, since only a fraction were natives of the ancient Roman province east of the Rhone. All wrote in “Provençal,” the language of southern France, properly the

langue d’oc

, as opposed to the

langue d’oil

of northern France (

oc

and

oïl:

“yes”). A Romance language surviving only as a dialect, the

langue d’oc

is closer to modern Portuguese or Spanish than to French. Four hundred and sixty names of troubadours have been preserved. The origins of a little more than half are known; of these one quarter came from Provence and one quarter from neighboring Languedoc. The rest came mostly from Périgord, Gascony, Limousin, La Marche, Auvergne, Quercy, Poitou, Rouerge, Dauphiné, Vienne, Velay—in a word, from all over southern France, while a handful had their origins in northern Italy or in Spain.

8

“Troubadour”

(trobaire)

derives from the word for the poet’s activity,

trobar

, whose modern French cognate is

trouver

, to find; the troubadour was a “finder,” a discoverer, inventor, creator. He was a composer of songs; troubadour poetry was meant to be sung. As a member of the knightly class, he was distinguished from the lower-class jongleurs, who were basically entertainers, not poets. (A modern scholar speculates that the jongleur, at first a juggler, acrobat, or magician, at some point added music to his act.) The troubadour might sing his own works or employ a jongleur to perform them. Some troubadours mention their jongleurs in their verse, or even address songs to them.