The Washington Manual Internship Survival Guide (19 page)

Read The Washington Manual Internship Survival Guide Online

Authors: Thomas M. de Fer,Eric Knoche,Gina Larossa,Heather Sateia

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine

The chest X-ray is by far the most common radiograph you will order and need to interpret. When reading a chest X-ray, like any radiograph, the most important consideration is to be systematic. Be sure to check the name and date on the image and compare with old images whenever possible.

Technique

•

Is the exposure correct? Underexposure can cause you to see things that aren’t there, while overexposure can cause pathology to disappear. You should be able to faintly see the intervertebral disc spaces through the cardiac silhouette.

•

Is the patient properly positioned? The spinous processes and trachea should be midline. The clavicular heads should be equidistant from the spinous processes. Rotated films distort the appearance of the cardiac silhouette and hila.

•

Is the frontal image posterior-anterior (PA) or anterior-posterior (AP)? AP images are often obtained in emergent situations or when the patient cannot stand. A two-view (PA and lateral) examination is optimal if the patient can tolerate it. A normal cardiac silhouette will appear larger on an AP exam due to its proximity to the X-ray source.

•

Was the image taken at full inspiration? Small lung volumes can produce vascular crowding and apparent mediastinal widening and atelectasis.

Lines and tubes

•

If the patient is intubated, check the position of the endotracheal tube (should be a minimum of 2 cm above the carina with 3 to 5 cm optimal).

•

Central venous catheters should follow expected venous courses and should generally terminate in the superior vena cava, near the level of the carina along the right aspect of the mediastinum. The end of the catheter should travel along the long axis of the superior vena cava (vertically).

•

Nasogastric and enteric feeding tubes may be partially visualized. Ensure they do not coil in the esophagus or extend outward into the lung due to endobronchial placement.

Airway

•

The trachea should be midline and not deviated.

•

The trachea will deviate away from the side of a pneumothorax if there is tension physiology. In cases of volume loss such as lobar collapse, it will deviate toward the affected side.

Bones

Systematically look at the sternum, ribs, clavicles, spine, and shoulders for fractures, osteolytic or osteoblastic lesions, and arthritic changes.

Diaphragm

•

The sides of the diaphragm should be equal and slightly rounded. The right side may be slightly higher. Elevation of one side may suggest paralysis, loss of lung volume on that side, diaphragmatic eventration, or diaphragmatic tear (in the setting of trauma).

•

Look for blunting of the costophrenic angles suggesting small pleural effusions, best seen on the lateral view.

•

Flat hemidiaphragms are indicative of hyperexpansion, often seen in emphysema.

•

Check for free air under the diaphragm on an upright radiograph, which can be seen with bowel perforation. If you think you’ve detected free intraperitoneal air, let your resident know right away.

Soft Tissues

Examine the soft tissues for symmetry, subcutaneous air, edema, and breast tissue.

Heart and Mediastinum

•

Maximal heart width greater than half of the chest width suggests cardiomegaly or pericardial effusion.

•

The aortic knob should be distinct.

•

Mediastinal widening may indicate thoracic aortic dissection or aneurysm, lymphadenopathy, or mass. In obese patients, it may be related to mediastinal fat deposition.

•

Mediastinal and tracheal deviation can be seen with a tension pneumothorax. As above, the trachea will deviate away from the side of the pneumothorax if tension physiology is present.

•

Use lateral images to confirm findings on frontal images and look for retrocardiac pathology, such as lower lobe pneumonias or hiatal hernias.

Hilar Structures

•

The left hilum is usually 2 to 3 cm higher than the right. They are generally of equal size.

•

Enlarged hila suggest lymphadenopathy or pulmonary artery enlargement. Use the lateral image to help differentiate.

Lung Markings

•

Look for normal lung markings all the way out to the chest wall to rule out pneumothorax. If lung markings are not seen to the periphery, look for a thin white visceral pleural line.

Be sure not to miss this! If you think you’ve detected a pneumothorax, let your resident know right away.

•

Normal lung markings taper as they travel out to the periphery and are smaller in the upper lungs. Lung markings in the upper lung fields that are as large as or larger than those in the lower lung (“cephalization”) suggest pulmonary edema.

•

Kerley’s B lines (small linear densities perpendicular to the pleural surface often best seen in the lung bases) are seen in congestive heart failure.

•

Hyperlucent lungs with increased retrosternal clear space on the lateral image are seen in emphysema.

•

Examine the lungs for areas of consolidation and nodules.

•

Obscuration of all or part of the heart border (silhouette sign) implies that a lesion is contiguous with or abuts the heart border and likely lies within the right middle lobe or lingula.

•

A small pleural effusion is suggested by blunting of the costophrenic angle, best seen on the lateral image. Larger effusions obscure the

shadow of the diaphragm and produce an upward-curving shadow along the chest wall. A straight horizontal air-fluid level indicates a concurrent pneumothorax (“hydropneumothorax”).

•

Lateral decubitus films can be done to ensure that the effusion is free flowing and large enough to attempt thoracentesis (usually > 1 cm on lateral film). The side of the effusion should be down.

PLAIN ABDOMINAL FILMS

Ordered quite frequently, plain abdominal films (“KUB” or “obstructive series”) are usually a first-line screening study and subsequent studies may be needed to clarify or identify pathology. An obstructive series consists of a frontal image and left lateral decubitus or upright image and should be ordered when evaluating for perforation or small bowel obstruction. Again, a systematic approach is key.

Bones

•

Examine the bones first or else you’ll forget.

•

Begin with the spine, then ribs, pelvis, and upper femurs. Look for arthritis, fractures, and osteolytic or osteoblastic lesions.

Lines and Tubes

•

Nasogastric/orogastric tubes should terminate in the left upper quadrant, with the proximal-most side port past the gastroesophageal junction.

•

Enteric feeding tubes should course past the stomach into the right abdomen and then cross back over the midline to the left (following the course of the duodenum) to terminate in the jejunum.

Soft Tissues

•

Systematically study the soft tissues looking for evidence of masses or calcifications. Calcifications can be seen over the gallbladder, renal shadows, ureteral courses; in the right lower quadrant (appendicolith); or overlying the uterus (fibroids). Phleboliths (vascular calcifications) are commonly seen in the pelvis and usually have a lucent center.

•

Be sure to carefully look for free air under the diaphragm (upright film) or next to the liver edge (left lateral decubitus film).

Free air is indicative of bowel perforation. If you see this, let your resident know immediately!

Gastrointestinal Structures

•

Look for the gastric bubble. A large air-distended stomach suggests some form of obstruction or dysfunction.

•

Observe the bowel gas pattern. A small amount of air is generally seen in the colon, while the small bowel is generally devoid of air. Fecal material is often visible in the colon although large amounts may be seen in constipation.

•

The colon may become distended (colon diameter >6 cm or cecum >9 cm) in colonic obstruction or ileus. Unless the distension is severe, the haustral markings are maintained. Large bowel markings are differentiated from small bowel markings by wider spacing and incomplete crossing of the lumen. When the ileocecal valve is incompetent, large bowel obstruction may also cause gaseous distension of the small bowel.

•

Distension of the small bowel (>3 cm in diameter) may be seen in mechanical obstruction or ileus. Small bowel striations are much more numerous, completely cross the lumen, and may become effaced with dilatation.

•

With mechanical obstruction, there is distension proximal to the obstruction and clearing of air distally. The appearance of ileus is much less distinct. There is discontinuous air in the small and usually large bowel. The degree of distension is also less remarkable.

•

Air-fluid levels unfortunately do not always distinguish mechanical obstruction from ileus, as they may be seen in both conditions.

PREPARATION FOR PROCEDURES

General Points

•

Perform plain radiographs prior to contrast studies. Perform iodinated contrast studies prior to barium studies. Barium can cause metallic streak artifact on CT, which obscures findings to the point that it may preclude the exam until the barium is cleared from the bowel.

•

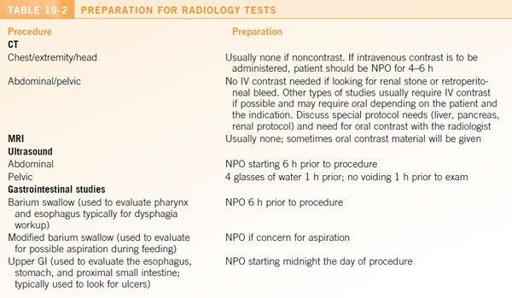

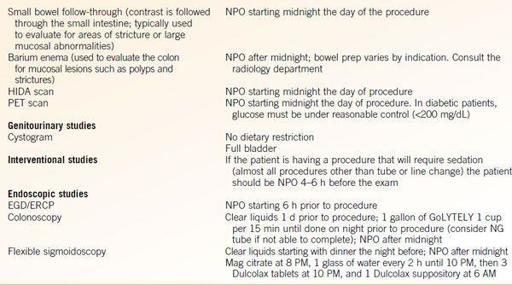

Consult your radiology department if you have questions about what study to order or to confirm preparation for procedures. Some preparations are institution specific (see

Table 19-2

).

•

Studies requiring no preparation include chest and abdominal radiographs, C-spine series, transthoracic echo, as well as those listed below.

•

Studies requiring the patient to be NPO include CT scans with contrast, abdominal ultrasound, gastrointestinal studies, HIDA scan, PET scan, and those listed below.

•

Remember to restart the diet postprocedure or if procedure is canceled.

Contrast Reactions

•

Everyone feels a sense of warmth or flushing and many patients experience nausea and/or vomiting during contrast administration— these are not allergies.

•

For known contrast sensitivity (e.g., hives, rash), consider prednisone, 50 mg PO q6h × 4 doses prior to the exam. The last dose should be administered 1 hour prior to the administration of contrast. Diphenhydramine, 50 mg PO, can also be added, 1 hour prior to contrast. Specific protocols vary by institution.

•

Although only nonionic contrast is used for CT (check your institution for confirmation), if your patient has had a major event with previous contrast administration (e.g., shock or airway compromise), discuss this with the radiologist prior to ordering a test. Patients who have had life-threatening reactions in the past should not receive intravenous contrast again, even with premedication. Allergic reactions generally do not occur with PO contrast.

•

The contrast used in MR examinations is a gadolinium preparation, not iodinated contrast. There is cross-reactivity in some patients, so those with severe contrast reaction to nonionic intravenous CT contrast should receive premedication for gadolinium contrast as well. See above for premedication regimen. Those with only mild sensitivity generally do not require premedication.

•

There is a relationship between gadolinium administration and nephrogenic systemic sclerosis in the setting of impaired renal function. Patients with creatinine clearance <30 and acute renal failure and/or those on dialysis are at higher risk. Consult with your radiologist about preparatory regimens, reduction in the gadolinium load, or performing the study without contrast.