The Washington Manual Internship Survival Guide (22 page)

Read The Washington Manual Internship Survival Guide Online

Authors: Thomas M. de Fer,Eric Knoche,Gina Larossa,Heather Sateia

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine

21

10 COMMANDMENTS OF CONSULTATION

Guiding principles for effective medicine consults were first suggested by Lee Goldman and colleagues in a paper published in the

Archives of Internal Medicine

in September 1983—they remain highly relevant today. The so-called 10 commandments for effective consultations are presented.

1. Determine the question being asked.

As a guiding principle, and when taking the initial phone call from the requesting service, always determine the specific medicine-related question he or she wants answered. This will be helpful, especially in situations in which the patient has an extensive and complicated previous medical history. Thus, a typical consultation note should begin by stating a specific problem, such as “Called to see this 78-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes and hypertension for perioperative glucose control ….”

2. Establish urgency.

Always determine if the consult is emergent, urgent, or elective.

3. Look for yourself.

Seldom do the answers to the consultation question lie in the chart; more often than not, independent data gathering is required, including reviewing prior admissions. Often the patient requires further testing. In many cases, the data review combined with a complete history and physical exam from an internal medicine perspective will establish the diagnosis.

4. Be as brief as appropriate.

It is not necessary to repeat in detail the data already in the primary team’s note; obviously as much new data independently gathered should be recorded.

5. Be specific.

Try to be goal oriented and keep the discussion and differential diagnosis concise. When recommending drugs, always include dose, frequency, and route.

6. Provide contingency plans.

Try to anticipate potential problems (e.g., if using escalating doses of a ß-blocker for rapid atrial fibrillation, make sure that regular BP checks are instituted). Staff (nursing/ancillary) on other floors are not used to treating medicine patients.

7. Honor thy turf.

Remember to answer the questions you were asked; it is not appropriate to engage the patient in a detailed discussion of whether surgery is indicated or likely to succeed. In situations in which you are asked by the patient about the surgical procedure, defer to the primary team rather than speculating on the technical aspects of the surgery.

8. Teach, with tact.

Share your insights and expertise without condescension.

9. Talk is cheap, and effective.

Communicate your recommendations directly to the requesting physician. There is no substitute for direct personal contact. Next month the shoe may be on the other foot, and the same resident may be coming to evaluate a surgical abdomen on one of your medicine admissions.

10. Follow up.

Suggestions are more likely to be translated into orders when the consultant continues to follow up.

PREOPERATIVE CARDIOVASCULAR RISK ASSESSMENT

•

Preoperative evaluation and intraoperative management are aimed at eliminating or treating risk factors to reduce the risk of cardiac events (MI, unstable angina, CHF, arrhythmia, and death).

•

Risk assessment guidelines have been published by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force (

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/116/17/e418.full.pdf

, last accessed June 22, 2012). History, physical examination, and ECG are important components of a thorough clinical assessment and help determine the extent of diagnostic testing required.

•

Patients who have mild CAD on cardiac cath or successful revascularization and have no new clinical symptoms probably have a similar risk for events as patients without CAD.

•

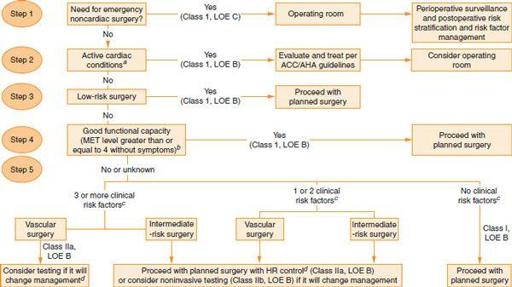

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association algorithm for preoperative cardiac risk assessment is detailed in

Figure 21-1

.

Figure 21-1.

ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: executive summary. (From Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery). Circulation. October 2007;116:e418-e499, with permission.)

a

Unstable coronary syndromes, decompensated CHF, significant arrhythmias, and severe valvular disease.

b

Walking at 4 mph on level ground, climbing stairs, climbing hills, riding a bicycle at 8 mph, golfing, bowling, throwing a baseball/football, carrying 25 lb (groceries from the store to the car), crubbing the floor, raking leaves, mowing the lawn.

c

Stable CAD, compensated or prior CHF, DM, CKD, and cerebrovascular disease.

d

Consider perioperative beta blockade. LOE, level of evidence; MET, metabolic equivalent.

•

β-blockers

: While multiple smaller studies support the use of perioperative β-blockade, the POISE trial, while confirming a decrease in cardiac events with aggressive β-blockade, showed an increase in overall mortality and stroke (

Lancet

2008;371:1839). The ACC/AHA recommendations were released before the POISE trial was published. Currently, it seems reasonable to treat high-risk patients (multiple clinical risk factors or with CAD), especially those undergoing vascular surgery (

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/120/21/e169.full.pdf

, last accessed June 21, 2012). β-blockers should be started as early as possible prior to surgery, with careful titration to a target resting heart rate of 50 to 60 bpm. Patients already taking ß-blockers should be continued on their medication.

•

ACE inhibitors should be considered for patients with systolic heart failure.

•

Patients taking calcium channel blockers should continue this medication throughout the perioperative period.

•

Continuation of preoperative antihypertensive treatment throughout the perioperative period is critical, particularly if the patient is on clonidine (risk of rebound hypertension). Consider switching the patient to IV or transdermal formulations of medications if the patient will be NPO for an extended period of time.

DERMATOLOGY

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

•

Emergency: call a dermatology consult immediately!

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is the most severe variant of a disease spectrum that consists of bullous erythema multiforme (EM) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS).

•

Pertinent information: Drug history.

Drugs are nearly always the cause;

TEN typically occurs within the first 8 weeks of therapy. The most common offenders are sulfonamides, anticonvulsants, penicillin, NSAIDs, antiretroviral medications, and allopurinol. Fewer than 5% of patients report no history of medication use.

•

Typical symptoms: Prodrome of high fever, cough, sore throat, burning eyes and malaise 1 to 3 days before the onset of skin involvement.

•

Physical exam: High fever, painful erythema of skin, blisters and/or erosions, mucosal erosions, and conjunctival erythema. Involvement of two or more mucosal surfaces is necessary for diagnosis. The skin eruption is usually painful, a key to making the diagnosis.

•

Workup: CBC, CMP, CXR (in the setting of respiratory distress), skin biopsy.

•

Diagnosis: physical exam findings and skin biopsy.

•

Degree of skin involvement: SJS <10%, SJS-TEN overlap 10% to 30%, TEN >30%.

•

Treatment:

•

Stop suspect drug(s) as well as all other nonessential medications.

• Transfer to burn unit/ICU.

• IV fluids, NG tube.

• Sterile protocol, antiseptic solution, and nonadherent dressings.

• Antibiotics only if high suspicion for sepsis.

• Consider

systemic steroids and/or IVIG

. Their use is decided on a case-by-case basis.

• Ophthalmology consult.

• OB/GYN consult for vaginal involvement; urology consult for urethral involvement.

•

Clinical pearls: Hepatitis occurs in 10%. Most patients have anemia and lymphopenia. Neutropenia is associated with poor prognosis. Hypothermia is more indicative of sepsis than fever. Patients with HIV, systemic lupus, or a bone marrow transplant have a higher risk of developing TEN.

•

Prognosis: TEN has a mortality rate of 30% to 40% and is most often secondary to sepsis, renal failure due to hypovolemic shock, or ARDS.

Toxic Shock Syndrome

•

Emergency: call an ID consult immediately!

•

Pertinent information: Age of patient, immunocompromised status, menstrual history, recent surgeries, diabetes, chronic cardiac or pulmonary disease.

•

History: Painful erythematous skin eruption, sudden onset of high fever, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, sore throat, confusion, headache, myalgias, and hypotension.

•

Physical exam: Fever >102°F; erythematous rash initially appearing on trunk, spreading to arms and legs and involving palms and soles, progressing to diffuse erythema and edema. Involves the oral mucosa. In 10 to 12 days there is desquamation of the top layer of the epidermis (not full thickness as in TEN).

•

Workup: Blood cultures, CBC (leukocytosis), CMP (hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, elevated LFTs), ECG (arrhythmias), CXR. To consider: serologic testing for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, leptospirosis, measles, hepatitis B surface antigen, antinuclear antibody, VDRL, monospot antibody, rapid strep test, LP (should be normal).

•

Diagnosis: Clinical (fever, typical rash, hypotension, multi-organ involvement).

•

Treatment:

•

Remove any infected foreign bodies.

•

Empiric IV antibiotics effective against

Streptococcus

and

Staphylococcus

:

clindamycin 900 mg IV plus IV vancomycin; tailor therapy when culture results available.

• Aggressive IV fluids.

•

Consider IVIG.

• Monitor for hypotension/shock.

• Oxygen therapy.

•

Clinical pearls: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome has a similar clinical picture; however, it occurs in immunocompromised adults.

Staphylococcus aureus

is the most common cause of TSS; however, exotoxin-producing streptococci can cause a similar clinical picture associated with higher mortality. Clindamycin suppresses synthesis of the TSS toxin (TSST-1), while ß-lactamase–resistant antibiotics may increase synthesis of TSST-1 and therefore should be included in the antibiotic regimen.

Necrotizing Fasciitis

•

Emergency: call a surgeon now!

•

Pertinent information: Recent surgical or traumatic wound.

•

Typical signs and symptoms: Involved area becomes erythematous, indurated, and severely painful. Within hours it can become dusky blue to black, indicating necrosis. Crepitus may be present due to subcutaneous gas formation.

•

Workup and diagnosis: Blood cultures, CK, plain radiography for soft tissue gas, and non-contrast CT if clinical diagnosis not obvious or to delineate depth of infection.

•

Treatment:

•

Wide surgical debridement

and tissue culture.

• Initial

empiric IV antibiotics

effective against streptococci, anaerobes, MRSA, and gram-negative bacilli. Include clindamycin in regimen.

•

Clinical pearls: Time is essential, call for surgical help immediately! Mortality rate is as high as 25%.

Pemphigus Vulgaris (PV) and Bullous Pemphigoid (BP)

•

Urgent dermatology consult.

•

Pertinent info: Flaccid or tense bullae, percentage of body surface area involved, mucosal involvement.