Throw Them All Out (19 page)

Read Throw Them All Out Online

Authors: Peter Schweizer

Disclosure statements may actually encourage conflicts of interest and embolden politicians who believe that since they report a certain transaction, it becomes okay to do it. Indeed, several studies by behavioral economists demonstrate that disclosures may make things worse, by producing "perverse incentives": once politicians sign a form, they may believe they are free and clear to do what they want.

19

***

So much for insider trading. What about broader conflicts of interest?

There are conflict-of-interest rules that apply to everyone in the executive and judicial branches of government, from the file clerk to the truck driver to judges to the secretary of defense. They are supposed to apply to the President too, and when it comes to personal finances, it does. But it is not illegal for a President to put fundraisers in charge of dispersing grants and loans to contributors and friends. Were a school superintendent to do this, he or she would be charged. But for a President? That's okay.

But these rules do not apply to legislators. They have their own. For the U.S. Senate, when it comes to raising conflict-of-interest concerns, the bar is set amazingly low: as long as a senator can prove that

at least one other person

besides himself benefits from a particular decision, he can pretty much use taxpayer money to enhance his own financial interests. The House rules are even worse. There is no such requirement.

20

What this means on a practical level is that politicians can and often do use taxpayer money to help their own businesses and enhance the value of their own real estate. They can procure federal funds to develop a site where they own a sizable chunk of real estate. As long as it also benefits a neighbor, this is entirely acceptable. A member of Congress can secure federal transportation money and extend a light rail transit system right in front of her own commercial building and it is acceptable. Were a corporate executive to do this with corporate funds, she would more than likely be in trouble.

If you work anywhere in Americaâa corporation, the government, or the nonprofit sectorâthere are whistleblower laws to protect you if you report financial crimes. In 1989, federal ethics rules protected whistleblowers from retaliation if they exposed financial corruption in government. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 extended those same protections to corporate America and nonprofit organizations. If you see your boss engaging in insider trading or fraud, you can report him to the authorities and you will be protected from retaliation. But Congress conveniently exempted itself from those requirements. Its members are effectively the only group of powerful people in America who can retaliate against whistleblowers who expose their financial crimes.

Â

Another example: extortion, a crime defined as a person getting or attempting to get money, property, or services from someone through coercion. That coercion may include the threat to harm someone, physically or otherwise.

When ordinary Americans engage in extortion, they get arrested. Consider the case of a Bradenton, Florida, businessman who owned a tanning spa. One customer claimed that she was burned by his tanning lamps, and she sued him. The case was settled by his insurance company. The businessman was upset, however, and after the settlement he sent a letter to her two attorneys demanding $5,000 from them or else he would send complaint letters to local and state agencies, the state bar association, and the attorney general's office. The attorneys called the police. The businessman was arrested for attempting to "extort money" from the lawyers.

21

Politicians have the power to extract wealth and favors based on their ability to help or harm people. While not as explicit as the extortion by the tanning spa owner, congressional extortion goes on regularly in Washington. When they want campaign contributions or preferential treatment, members of Congress may threaten businesses or individuals with harmful legislation. There is a name for this type of coercion: "juicer bills" or "milker bills," designed to "juice" and "milk" campaign contributions and favors from businesses and industries. Professor Fred McChesney, who teaches law at Northwestern University, says this is nothing short of "political extortion." Politicians threaten to tax something or regulate something in order to extract a campaign contribution, or even for personal financial gain.

22

How powerful is this weapon? The mere threat of adverse legislation can affect a company's stock price. Two academics looked at thirty cases in which businesses were threatened with political action and the threats were later retracted. The study found that those threats "significantly" affected the stock prices of companies.

23

Milker bills are often introduced in the area of taxes, says McChesney. Members of Congress threaten to impose a new tax and then withdraw the bill after campaign contributions flow in. Of course, the contributions were the point in the first place.

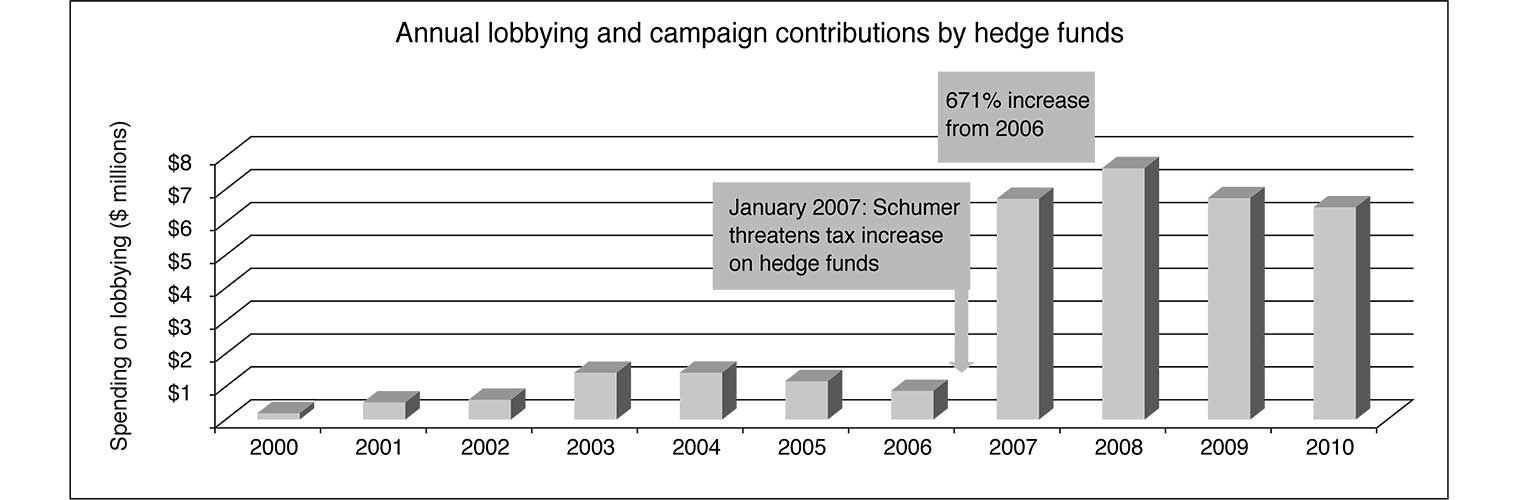

In the summer of 2006, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid announced that he wanted a tax hike on hedge funds. At the time those funds were taxed at the capital gains rate of 15%. Reid declared that Democrats would put at the top of their agenda taxing hedge fund profits as regular income rather than as capital gains, meaning rates of 25% or higher. So they began working on legislation.

In late January 2007, shortly after the Democrats had captured both houses of Congress, Senator Charles Schumer sat down to dinner with a number of top hedge fund managers at Bottega del Vino in Manhattan. The net worth of the managers at the table totaled more than $100 billion. As the

New York Times

recounted, hedge funds up to this point had spent very little money on lobbying and campaign contributions. They were quite content to be left alone by Washington. But Schumer, who headed the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, wanted to change that. And with the threat of a tax increase, suddenly the hedge funds became very generous. According to the Federal Election Commission, over the course of the next eighteen months, hedge funds dumped nearly $12 million into campaign accountsâwith 83% of the money going to Democrats. John Paulson, one of the most successful hedge fund managers, held fundraisers for the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee. James Simons, a hedge fund manager who made $1.7 billion in 2006 alone, donated $28,500 to the DSCC, and Schumer raked in $150,000 for his campaign chest. Bain Capital and Thomas H. Lee Partners, both Boston-based investment houses with hedge funds, gave generously to Senator John Kerry.

PAY UP, OR ELSE

Â

Â

The political class also profited indirectly, because the hedge funds hired lobbyists, often the friends and former aides of politicians, to fight the bill. The Blackstone Group, which manages a huge hedge fund, had previously spent $250,000 a year on lobbying. Now Blackstone hired a number of Democratic Party lobbyists, including Schumer's former staff counsel, and spent more than $5 million on lobbying in 2007 alone. The Managed Funds Association, a lobbying group for hedge funds, also hired Democratic Party lobbyists, including a firm that employed Schumer's former aide for banking issues. Overall, dozens of former Democratic congressional staffers were hired with lucrative contracts to fight the bill.

Then, in the late fall of 2007, Senator Reid and his colleagues suddenly changed their tune. The Senate schedule, it seemed, was just too crowded to deal with the issue. The threat of a tax increase for hedge funds was withdrawn.

Politicians are so good at throwing their weight around that the banking industry had to lobby for legislation that would prohibit banks from lending to congressional candidates during election time. Why would they do that? Presumably out of fear that politicians would pressure them for special deals.

In our system of government, the legislative branch polices itself and the President is allowed to skirt conflict of interest laws because, well, he's the president. It is time for that to change.

Government is a trust, and the officers of the government are trustees, and the both, the trust and the trustees, are created for the benefit of the people.

âHENRY CLAY

Â

T

HERE'S A STORY

about a politician who returns from Washington to his home district to run for reelection. When his constituents learn that he is not yet a millionaire, they promptly vote him out of office. He

must

be stupid.

There seems to be only one sure-fire way to prevent the Permanent Political Class from getting drummed out of power: maintain extremely low standards. We have come to accept minor indiscretions, financial malfeasance, and profiteering on the taxpayer dime as regular occurrences. And as those indiscretions and crimes (for the rest of us) mount up and become more common, we become even more tolerant of them. The standards become lower still. To steal a phrase from the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (on a different subject), we have defined deviancy down in Washington. The quality of our leadership is so low because we expect so little.

The political class is able to exploit honest graft because they have been given a position of privilege and power, and they work very hard to persuade us that their well-being is necessary for our well-being. They work very hard to persuade us that they, and only they, are capable of "running" the country, or "managing" the economy. This, of course, is the classic appeal of the con: I may be a rogue, but I'm indispensable. George Washington Plunkitt made a similar appeal for Tammany Hall. Without the political machine in place, he warned, "it would mean chaos. It would be just like takin' a lot of dry-goods clerks and settin' them to run express trains."

1

At the root of the Permanent Political Class is a profound sense of arrogance. A good military commander should never consider himself to be irreplaceable, but many politicians in Washington believe precisely that of themselves. It is an ugly form of elitism, less overt than what we would see from the royalty of Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the Sun King could proclaim, "I am the state." The modern, subtler version of this arrogance is the politician's belief that if we restrict his ability to engage in legal graft, the nation will suffer, because we won't be able to attract bright people (like them!) to run the country.

Over the past forty years we have been governed by the best-educated political class in our history. Today, debts mount, the financial markets are in turmoil, the economy is in terrible shapeâand the Washington games continue. The problem is not a lack of smart people in Washington. There is no "smart gap." There is, however, a "character gap." Like the financial crisis on Wall Street, the root of the problem is not ignorance but arrogance.

The Permanent Political Class tells us: We need them. Only they can dissect the entrails of the latest bill or understand the complexities of financial reform. They are making so many sacrifices on our behalf, they say. They are smart and well educated and could be making a lot more money somewhere else, they claim. We should tolerate a little honest graft on the side, or the occasional financial indiscretion, like failing to report income on their tax returns.

Yet, of course, the political class is hardly the only group of people in the country making a sacrifice for public service. Our soldiers are underpaid. Those who enter West Point, the Air Force Academy, or Annapolis, or those who go through ROTC at a rigorous school, are just as smart. They certainly could be doing something else with their time. They choose the armed forces as an act of service; they are not looking to get rich as officers. Enlisted soldiers are not looking to cash in by joining the infantry. In the military they will never earn anything close to what they might earn in the private sector. And many of our best leaders over the last century or more have come out of our armed services. These are individuals who could have been running large corporations or institutions for far more money. Two-, three-, and four-star generals make less than a freshman member of Congress, even though they may be responsible for the safety and operation of more than 100,000 troops. If today we had a five-star general like Dwight Eisenhowerâand we don'tâhe would still be paid less than a freshman congressman.

2

And yet it is impossible to imagine that the military brass would ever argue that they deserve to make a little "on the side" as indirect compensation for their service.

Indeed, in the early 1980s, when the United States was in the midst of another (smaller) budgetary crisis, President Ronald Reagan released to the public letters he had received from American soldiers serving in Europe. They weren't griping about possible cuts. Just the opposite: they offered to take a pay cut if it would help the country. When was the last time you heard a member of the Permanent Political Class offer to do that?

When Gordon England was appointed to become deputy secretary of defense in 2006, members of the Senate committee that would hold hearings and vote on his confirmation had a simple and blunt request: You must give up the lucrative stocks and options you have in companies that do business with the Pentagon. Such divestment had been a requirement of the Senate Armed Services Committee of senior Pentagon appointees for decades, designed to eliminate any "military-industrial complex" conflict-of-interest concerns that might arise. The restriction was not limited to just missile manufacturers or companies that made bullets. "We're not allowed to buy Coca-Cola stock because military guys drink Coke," said England, "and we couldn't have stock in cereal companies because military guys eat cereal."

3