Two Miserable Presidents (14 page)

Read Two Miserable Presidents Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

N

ow back to Pennsylvania for the battle of Gettysburg.

ow back to Pennsylvania for the battle of Gettysburg.

The whole thing got started when Southern soldiers heard that there was a large supply of shoes in the nearby town of Gettysburg.

Thousands of Lee's men were desperate for a new pair of shoes. One barefoot Confederate named John Hancock had tried to make his own sandals out of raw cowhide. He found the results disappointing. “They flop up and down, they stink very bad, and I have to keep a brush in my hand to keep the flies off of them.” he said.

Thousands of Lee's men were desperate for a new pair of shoes. One barefoot Confederate named John Hancock had tried to make his own sandals out of raw cowhide. He found the results disappointing. “They flop up and down, they stink very bad, and I have to keep a brush in my hand to keep the flies off of them.” he said.

On June 30, the Confederate general Henry Heth found his commander, A.P. Hill, and said, “If there is no objection, I will take my division tomorrow and go to Gettysburg and get those shoes.”

“None in the world,” Hill replied.

So Heth's men set out to find those shoes.

T

he next day, fifteen-year-old Tillie Pierce was sitting in class at the Young Ladies Seminary of Gettysburg. She and the other students were working on their literature lessons when the teacher suddenly announced: “Children, run home as quickly as you can!”

he next day, fifteen-year-old Tillie Pierce was sitting in class at the Young Ladies Seminary of Gettysburg. She and the other students were working on their literature lessons when the teacher suddenly announced: “Children, run home as quickly as you can!”

Everyone jumped up and raced out the door. “Some of the girls did not reach their homes before the rebels were in the streets,” Tillie said. “I had scarcely reached the front door, when, on looking up the street, I saw some of the men on horseback. I scrambled in, slammed shut the door, and hastening to the sitting room, peeped out between the shutters.”

The Confederate soldiers did not find any shoes in Gettysburg. They did, however, run into a few thousand Union soldiers. No one planned to have a battle here. But when the enemies bumped into each other in town, the men simply did what they had been doing for the past two yearsâthey started fighting, and fighting hard. And that's how the biggest battle of the war began.

When the shooting started, one local farmer looked nervously out at his field. He saw his cow chomping grass on what was about to

become a battlefield. “Tell Lee to hold on just a little,” he shouted to Southern soldiers, “until I get my cow in out of the pasture.” And he ran off to get his cow.

become a battlefield. “Tell Lee to hold on just a little,” he shouted to Southern soldiers, “until I get my cow in out of the pasture.” And he ran off to get his cow.

John Burns, another local resident, sat in his house, listening to the gunshots growing louder and louder. This seventy-year-old veteran of the War of 1812 took his ancient musket down from the wall and started cleaning it. His wife wanted to know what he was doing.

“I thought some of the boys might want the old gun,” he said.

Then a group of Union soldiers marched past his house, and Burns jumped up and headed for the door.

“Burns, where are you going?” his wife asked.

“I am going out to see what is going on.”

And next thing you know, John Burns, wearing his War of 1812 army jacket, was marching into battle with the boys of the Seventh Wisconsin. As they headed into combat, the soldiers gave Burns a new rifle. They offered him an ammunition box, but he said he liked to keep his bullets in his pants pocket.

“I can get my hands in here quicker than in a box. I'm not used to them new-fangled things.”

Burns was wounded three times, and when his regiment was driven back he was left lying on the ground. Hours later some kind Confederate soldiers found him and carried him home.

John Burns

M

eanwhile, a wild day of fighting was raging all over Gettysburg. Neither army had a plan. Robert E. Lee and George Meade were still on their way to town, and neither commander really knew what was going on. But remember, soldiers on both sides had been expecting a big battle. So they figured this must be it. As a Polishborn Union officer named Wlodzimierz Krzyzanowski (his men called him “Kriz”) explained: “The fate of the nation was at stake. I felt it, the leaders felt it, the army felt it, and we fought like lions.”

eanwhile, a wild day of fighting was raging all over Gettysburg. Neither army had a plan. Robert E. Lee and George Meade were still on their way to town, and neither commander really knew what was going on. But remember, soldiers on both sides had been expecting a big battle. So they figured this must be it. As a Polishborn Union officer named Wlodzimierz Krzyzanowski (his men called him “Kriz”) explained: “The fate of the nation was at stake. I felt it, the leaders felt it, the army felt it, and we fought like lions.”

As more and more soldiers from both armies reached town, the battle got bigger and bigger. It actually got so loud that people in Pittsburgh, 150 miles away, heard the explosions.

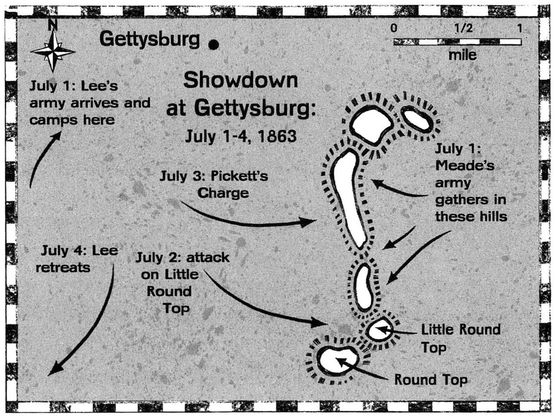

General Lee arrived in Gettysburg that afternoon and studied the situation through his binoculars. He was pleased to see that his army was driving Union forces out of the town

Instead of panicking, though, as they had done in a few previous battles, Union soldiers were gathering in large numbers on the hills just south of town. This was largely thanks to a cool-headed Union general named Winfield Hancock, who took charge on those hills and kept his men calm. “I think this is the strongest position by nature on which to fight a battle that I ever saw,” Hancock said.

Lee watched all this through his binoculars as the sun went down. He could see that the Union army was now in a strong position. General James Longstreet, Lee's second-in-command, thought the Confederate army should leave town and find a different place to fight.

“No,” said Lee, “the enemy is there, and I am going to attack him there.”

“If he is there, it will be because he is anxious that we should attack him,” Longstreet argued. “A good reason, in my judgment, for not doing so.”

Lee respected Longstreet's opinion (he called Longstreet his “Old War Horse”). But Lee hadn't gotten this far by playing it safe. “They are there in position,” Lee said. “And I am going to whip them or they are going to whip me.”

The Union commander George Meade. finally showed up at about midnight. He met with Hancock and his other generals, who all told him the Union army was in a good spot for tomorrow's fight. “I am glad to hear you say so, gentlemen,” Meade said, “for it is too late to leave.”

Both armies tried to get some sleepâbut everyone was feeling the pressure. “This is the turning point,” one Union soldier said to his friend. “If Lee whips us here the Union is lost.”

T

he soldiers of the Twentieth Maine Regiment arrived in Gettysburg on the morning of July 2âand they were already exhausted. These men, mainly young fishermen and lumberjacks, had marched more than 125 miles in the past six days. But there was no time to rest.

he soldiers of the Twentieth Maine Regiment arrived in Gettysburg on the morning of July 2âand they were already exhausted. These men, mainly young fishermen and lumberjacks, had marched more than 125 miles in the past six days. But there was no time to rest.

As soon as they got to Gettysburg, the Twentieth Maine was placed on a rocky, wooded hill called Little Round Top. This was a super-important spot because it was the very left end of the entire Union line. If Union soldiers lost control of this spot, Confederate forces could storm around the end of the Union army and surround itâthen capture or kill the whole Union force.

This is exactly what Lee was hoping to do. He ordered a massive attack on the left edge of the Union army.

When the firing started, Colonel Strong Vincent shouted some last-second orders to Joshua Chamberlain, commander of the Twentieth Maine, “This is the left of the Union line. You understand. You are to hold this ground at all costs!”

A year before Chamberlain had been a college professor in Maine. Now he had a very different jobâhe and his men were to die on this spot rather than retreat or surrender.

Bombs started crashing into the trees on Little Round Top, sending thick branches spinning through the air. Joshua Chamberlain decided his two brothers were standing too close to him. “Boys, I don't like this,” he told Tom and John Chamberlain. “Another such shot might make it hard for Mother.” The brothers spread out.

Down at the bottom of the hill, Colonel William Oates, commander of the Fifteenth Alabama, was giving his men a moment of rest. These young farmers were just as tired as the Maine menâthey

had marched twenty-eight miles in the past twelve hours. “Some of my men fainted from the heat, exhaustion, and thirst,” Oates remembered. And now it was their job to charge up Little Round Top.

had marched twenty-eight miles in the past twelve hours. “Some of my men fainted from the heat, exhaustion, and thirst,” Oates remembered. And now it was their job to charge up Little Round Top.

Oates sent a few soldiers off to fill the men's empty canteens. But while waiting for the water, the regiment was ordered to attack immediately. The men desperately needed something to drinkâbut orders were orders. They started up the hill.

“Look! Look!” shouted the men of the Twentieth Maine when they saw the Alabama soldiers coming up through the trees. This was the start of a ferocious fight in which the soldiers slammed together and drove each other up and down the hill.

“How can I describe the scenes that followed?” wondered Theodore Gerrish of Maine. “Cries, shouts, cheers, groans, prayers, curses, bursting shells, whizzing rifle bullets and clanging steel ⦠. The lines at times were so near each other that the hostile gun barrels almost touched.”

Both commanders were surrounded by wild fighting and confusion. “At times I saw around me more of the enemy than of my own men,” remembered Chamberlain. “My dead and wounded ⦠literally covered the ground,” Oates said. “The blood stood in puddles in some places on the rocks.” Still, he kept leading charge after charge up the hill.

Chamberlain's men were firing so furiously, they ran out of bullets. They grabbed bullets from the wounded and dead, and then ran out of those too. They knew another attack was coming at any minute, and they couldn't just sit there waiting with no ammunitionâbut they couldn't leave. Chamberlain had an idea. “As a last, desperate resort, I ordered a charge,” he said.

“Bayonet!” Chamberlain shouted.

The Maine men attached their bayonets to the ends of their rifles. They jumped up, and with what Theodore Gerrish described as “one wild yell,” started running down the hill. “We struck them with a fearful shock,” Gerrish said.

The bloodied and exhausted survivors of the Fifteenth Alabama retreated down the hill. The left end of the Union line was safe.

“There never were harder fighters than the Twentieth Maine men and their gallant Colonel. His skill ⦠and the great bravery of his men saved Little Round Top and the Army of the Potomac.”

William C. Oates

If the men of the Twentieth Maine had lost Little Round Top, the whole history of the warâand the whole history of the United Statesâmight have been different. And for the rest of their lives, the veterans of the Fifteenth Alabama insisted that they would have taken Little Round Top, if only they had been allowed to have a drink of water before going into battle.

Other books

The Last Legacy (Season 1): Episodes 1-10 by Lavati, Taylor

Wolf at the Door by Sadie Hart

Response by Paul Volponi

Follow (Social Media #1) by Ja Huss

Baby Love by Joyce Maynard

WanttoGoPrivate by M.A. Ellis

Dark Star by Roslyn Holcomb

Shiv Crew by Laken Cane

A Case for Love by Kaye Dacus