Two Miserable Presidents (13 page)

Read Two Miserable Presidents Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

I

f you think Jefferson Davis was depressed, wait till you hear about Abraham Lincoln.

f you think Jefferson Davis was depressed, wait till you hear about Abraham Lincoln.

A journalist named Noah Brooks was with Lincoln when a telegram arrived describing Hooker's defeat at Chancellorsville. As Lincoln read the paper, Brooks watched the president's face turn a sickly gray.

“Never, as long as I knew him, did he seem to be so broken, so dispirited, so ghostlike,” Brooks said.

Lincoln clasped his hands behind his back and started pacing back and forth, saying:

“My God! My God! What will the country say!

What will the country say!“

What will the country say!“

Abraham Lincoln

The country said a lotâsome of it too rude to print here. The basic idea was that Lincoln was messing up, he was losing the war. More and more people were calling for Lincoln to admit defeat and let the South have its independence. But Lincoln was as determined as ever to preserve the Union.

While trying to figure out exactly how to do that, Lincoln had to deal with the annoying day-to-day details of his job. Unlike today, anyone could walk right into the White House and ask to meet the president. Even in the middle of the war, tourists, honeymooners, and soldiers lined up to meet Lincoln and shake his hand. People came to show him inventions or ask for jobs in the government. One guy showed up asking to be made ambassador to Germany or France. When he was told those positions were taken, the man said, “Well, then, will you lend me five dollars?”

A teenage boy complained that he had been hired to deliver horses to Washington. He did the job, but his boss never paid him. Now he had no money to get home.

Lincoln:

What do you want me to do?

What do you want me to do?

Kid:

I want you to send me home.

I want you to send me home.

Lincoln:

I have no fund which I can apply to such a purpose.

I have no fund which I can apply to such a purpose.

Kid:

I don't know what to do.

I don't know what to do.

Lincoln:

I'll tell you what I would have done when I was a young fellow like you. I would have worked my own way back.

I'll tell you what I would have done when I was a young fellow like you. I would have worked my own way back.

Another man wanted to use Lincoln's name in an advertisement. The normally patient Lincoln finally exploded. “You have come to the wrong place,” he shouted. “There is the door!”

In June 1863 Lincoln got something much more serious to worry aboutâLee's army was in the North again.

F

ollowing up his victories in Virginia, General Lee decided to try another invasion of the North. He knew that Northerners were getting discouraged and tired of war. And he hoped that one more Southern victory would convince them to give up the fight.

ollowing up his victories in Virginia, General Lee decided to try another invasion of the North. He knew that Northerners were getting discouraged and tired of war. And he hoped that one more Southern victory would convince them to give up the fight.

This was a very real possibility, and Lincoln knew it. He did not want the fate of the nation resting in the shaky hands of “Fighting Joe” Hooker. So he changed generals again!

On the night of June 28, a Union general named George Meade was fast asleep in his tent. At about three a.m. Meade heard someone saying his name and he opened his eyes and saw an officer leaning over his cot.

“General, I'm afraid I've come to make trouble for you,” the man said.

I'm being arrested,

Meade thought.

I wonder why?

Then the man handed Meade a note that said: “You will receive with this the order of the President placing you in command of the Army of the Potomac.”

Meade thought.

I wonder why?

Then the man handed Meade a note that said: “You will receive with this the order of the President placing you in command of the Army of the Potomac.”

Meade didn't want the job. He actually tried to argue with the officer who brought the message, which was fairly pointless, since the guy was only delivering Lincoln's orders. Meade was taking over an army that had been badly whipped in its last few fights. And now General Lee's army was marching Northâanother major battle was coming any day.

Soon after Lee's army crossed into Northern territory, a Southern soldier named William Christian wrote a letter home. “My own darling wife,” wrote Christian. “We crossed the line day before yesterday and are resting today near a little one-horse town on the road to Gettysburg. Of course we will have to fight here, and when it comes it will be the biggest on record.”

He was right.

The Union army followed General Lee's soldiers into Pennsylvania, marching twenty miles a day under a scorching sun. Union men tossed away their extra clothesâit was just too hot to carry heavy backpacks.

As they splashed through streams, soldiers took off their dusty shirts and rinsed them quickly and hung them on the tops of their rifles to dry. They marched on with their shirts on their guns, flapping like flags in the summer wind.

T

he good news for Union soldiers was that they were finally back on Northern soilâfriendly territory, that is. Citizens came out to cheer and give them food. A nineteen-year-old soldier named Jesse Young remembered marching past a schoolhouse and watching boys and girls pour outside. Waving flowers and flags, the students greeted the weary soldiers with a popular Union song:

he good news for Union soldiers was that they were finally back on Northern soilâfriendly territory, that is. Citizens came out to cheer and give them food. A nineteen-year-old soldier named Jesse Young remembered marching past a schoolhouse and watching boys and girls pour outside. Waving flowers and flags, the students greeted the weary soldiers with a popular Union song:

“Yes, we'll rally round the flag, boys, we'll rally once again,

Shouting the battle cry of Freedom;

We'll rally from the hillside, we'll gather from the plain,

Shouting the battle cry of Freedom!”

Shouting the battle cry of Freedom;

We'll rally from the hillside, we'll gather from the plain,

Shouting the battle cry of Freedom!”

“Many strong men wept as they looked on the scene,” Young said.

Southern soldiers got a different greetingâusually curious stares or cold silence. General Lee did have some fans in the North, though. One woman asked for his autograph. Another asked for a lock of his hair. “General Lee said that he really had none to spare,” a Southern officer remembered.

Lee's army continued north, capturing supplies, and some soldiers too. James Hodam's regiment captured a very young Union drummer boy. Drummer boys had the important job of sending signals to soldiers by beating rhythms on their drums. Some were twelve or even younger.

Hodam and the boy had this conversation:

Hodam:

Hello, my little Yank. Where are you going?

Hello, my little Yank. Where are you going?

Drummer

Boy: Oh, I am a prisoner and am going to Richmond.

Boy: Oh, I am a prisoner and am going to Richmond.

Hodam:

Look here, you are too little to be a prisoner. So pitch that

drum into that fence-corner, throw off your coat, get behind those bushes, and go home as fast as you can.

Look here, you are too little to be a prisoner. So pitch that

drum into that fence-corner, throw off your coat, get behind those bushes, and go home as fast as you can.

Drummer Boy:

Mister, don't you want me for a prisoner?

Mister, don't you want me for a prisoner?

Hodam:

No

.

No

.

Drummer Boy:

Can I go where I please?

Can I go where I please?

Hodam: Yes.

Drummer Boy:

Then you bet

Then you bet

I am going home to Mother!

The kid tossed away his drum and army coat and dove into the bushes by the side of the road. “I sincerely hope he reached home and Mother,” Hodam said.

Let's hope so. The biggest battle ever fought on American soil was about to begin.

B

ut before it does, we've got to check in on the action in the westâevents out there were also speeding toward a major turning point.

ut before it does, we've got to check in on the action in the westâevents out there were also speeding toward a major turning point.

The scene of the showdown was the Mississippi River. The South still controlled a 140-mile section of the river running through Mississippi and Louisiana. And they were desperate to keep it. If the North gained control of the entire Mississippi River, the Confederacy's land would be sliced in two.

Slicing the Confederacy in two was exactly what General Ulysses S. Grant had in mind. His main problem was the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, located on steep hills three hundred feet above the Mississippi River. As long as the Confederates held this spot, they could keep control of at least part of the river. Vicksburg, said Jefferson

Davis, “held the South's two halves together.”

Davis, “held the South's two halves together.”

Grant spent the early months of 1863 trying, and failing, to attack Vicksburg. Actually, his army couldn't even get thereâit kept getting stuck in the muddy forests and overgrown swamps around the city. Impatient Northern newspapers were again demanding that Grant be fired.

“I think Grant has hardly a friend left, except myself,” Lincoln said. “I propose to stand by him.”

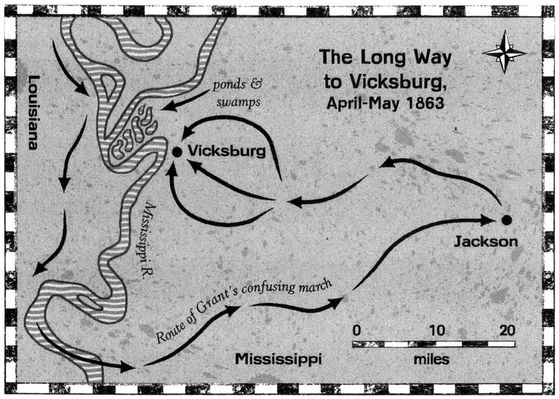

Lincoln never regretted that decision. Grant showed that he had something in common with Robert E. Leeâhe would take big risks to achieve big goals. In April he marched 40,000 men far to the south of Vicksburg, crossed the river, and headed into Mississippi with only the food his men could carry on their backs.

“I was now in the enemy's country, with a vast river and the stronghold* of Vicksburg between me and my base of supplies. But I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy.”

Ulysses S. Grant

There were about 30,000 Confederate soldiers defending Vicksburg. Instead of heading straight for them, Grant confused everyone (including a very nervous Abe Lincoln) by leading his army east, away from Vicksburg. Moving quickly, keeping Confederate generals guessing, Grant's army zigzagged 180 miles over the next few weeks, winning battles and destroying railroads. Then Grant swung around and headed for Vicksburgâand his plan suddenly became clear. He had been beating or chasing away Confederate forces all over the state. Now the Confederate soldiers in Vicksburg were all alone, cut off from outside help.

Northern newspapers stopped calling Grant a drunken loser. Now he was a hero, even a genius. Lincoln joined the praise, calling Grant “a very determined little fellow.”

By the end of May, Grant's army had Vicksburg surrounded. “A cat could not have crept out of Vicksburg without being discovered,” said one Confederate soldier. There were still 30,000 Confederate

troops in town, though. And they were not about to let Grant come in. Colonel James L. Autry declared: “Mississippians don't know, and refuse to learn, how to surrender to an enemy.”

troops in town, though. And they were not about to let Grant come in. Colonel James L. Autry declared: “Mississippians don't know, and refuse to learn, how to surrender to an enemy.”

Grant decided to teach them.

H

e got some help from the Union army's first African American soldiers. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation opened the door for African Americans to enlist in the United States Army. And thousands raced to volunteer.

e got some help from the Union army's first African American soldiers. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation opened the door for African Americans to enlist in the United States Army. And thousands raced to volunteer.

When a Union general called for black volunteers in New Orleans, a hundred African American shop owners immediately closed their doors and rushed to join the army. These men became part of the First Louisiana Native Guard, the first black regiment in the Union army. The regiment's highest-ranking black officer was Captain André Cailloux, a thirty-eight-year-old cigar factory owner and boxer. One of the youngest volunteers was sixteen-year-old John Crowder, who said he joined the army for two reasons: to serve his country, and to earn money to help his mother.

African American volunteers faced serious prejudice in the army. They were even paid less than white volunteersâstarting pay was ten dollars a month for black soldiers, thirteen dollars for white soldiers. (Black soldiers protested this injustice and were finally granted equal pay in 1864.) Many white military leaders and politicians openly doubted that African Americans would succeed as combat soldiers. “Will they fight?” was a question printed in newspapers all over the country.

These new soldiers realized they would be facing more than enemy bullets and bombs. Fair or not, they would be fighting on behalf of all black Americans. In a letter to the Union general Nathaniel Banks, a

group of Louisiana volunteers boldly accepted this challenge: “If the world doubts our fighting,” they wrote, “give us a chance and we will show them what we can do.”

group of Louisiana volunteers boldly accepted this challenge: “If the world doubts our fighting,” they wrote, “give us a chance and we will show them what we can do.”

The soldiers got their chance when Union generals decided to attack the Confederate fort at Port Hudson, Louisiana. Along with Vicksburg, this was the last fort on the Mississippi River still in Southern hands. Captain André Cailloux and his men were assigned a leading role in the attack. When he was given the dangerous job of carrying one of the First Louisiana's battle flags, a soldier named, Anselmo Planciancios was ready:

“I will bring back these colors in honor, or report to God the reason why.”

Anselmo Planciancios

As soon as the charge toward Port Hudson began, André Cailloux was shot through the left arm. He held his sword high in his right hand and shouted, “Follow me!”âand charged at the guns again.

“They charged and re-charged and didn't know what retreat meant,” said a white soldier who fought at Port Hudson.

But the Confederate fort was just too strong. Cailloux was shot again and killed. Planciancios was hit in the head and died instantly. The attack ended in failure as darkness fell.

Though the black soldiers had not captured Port Hudson, their bravery and skill changed minds all over the country. “They fought

splendidly,” reported General Nathaniel Banks.

splendidly,” reported General Nathaniel Banks.

Black soldiers soon saw more action when they were attacked at Milliken's Bend, a Union supply post on the Mississippi River. In brutal hand-to-hand fighting with bayonets and rifle butts and fists, they helped defeat the Confederate attack.

Grant was impressedâand convinced he could rely on African American soldiers. And the recent action helped him tighten his grip around the throats of Port Hudson and Vicksburg. Both places started running out of food. A Confederate officer at Port Hudson remembered eating the army mules (“quite tender and juicy”), and then getting even more desperate:

“Rats, of which there were plenty about ⦠were also caught by many officers and men and were found to be quite a luxuryâsuperior, in the opinion of those who eat them, to spring chicken.”

Rats may have tasted good, but they wouldn't last forever.

Other books

Beautiful Monster: The Hunt (Book 2) by Jeanne Bannon

Second Hand (Tucker Springs) by Heidi Cullinan, Marie Sexton

The Coffin Quilt by Ann Rinaldi

The Oil Tycoon and Her Sexy Sheikh by Ros Clarke

The Power of the Legendary Greek by Catherine George

Memories of a Marriage by Louis Begley

Mated (The Sandaki Book 1) by Gwendolyn Cease

Take Me in Tahoe by Shelli Stevens

Rival Demons by Sarra Cannon

Demon's Daughter (Demon Outlaws) by Altenburg, Paula