Two Miserable Presidents (17 page)

Read Two Miserable Presidents Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

B

ut this was a wild and massive war, and sometimes bad news and good news came at the same time. If Abe Lincoln had picked up a Boston newspaper called

The Commonwealth

on July 10, 1863, he would have read a story that began with this remarkable sentence: “Colonel Montgomery and his gallant band of 300 black soldiers, under the guidance of a black woman, dashed into the enemy's country, struck a bold and effective blow ⦠without losing a man or receiving a scratch.”

ut this was a wild and massive war, and sometimes bad news and good news came at the same time. If Abe Lincoln had picked up a Boston newspaper called

The Commonwealth

on July 10, 1863, he would have read a story that began with this remarkable sentence: “Colonel Montgomery and his gallant band of 300 black soldiers, under the guidance of a black woman, dashed into the enemy's country, struck a bold and effective blow ⦠without losing a man or receiving a scratch.”

The black woman in question was Harriet Tubman, the former Underground Railroad heroâknown to her admirers as “General Tubman.”

When the Civil War began, Tubman went to work for the Union army as a cook and nurse. She didn't stop there. While working with the army in South Carolina, Tubman boldly slipped into Confederate

territory, gathering information from slaves she met and studying the local geography. Then she came up with a plan.

territory, gathering information from slaves she met and studying the local geography. Then she came up with a plan.

On the night of June 2, 1863, three Union gunships cruised up the Combahee River. Aboard the ships were the black soldiers of the Second South Carolina Regiment. Guiding the lead boat was Harriet Tubman.

Tubman knew exactly where to find warehouses piled high with cotton and rice. Union soldiers jumped off the boats, setting fire to the warehouses and taking the opportunity to torch the homes of plantation owners as well. At the same time, entire families of escaping slaves raced to the riverbank and leaped to freedom on the Union boats. “I never saw such a sight,” Tubman said.

“Women would come with twins hanging around their necks ⦠bags on their shoulders, baskets on their heads, and young ones tagging along behind, all loaded; pigs squealing, chickens screaming, young ones squealing.

Harriet Tubman

Tubman's Combahee River raid was a smashing success. Union soldiers destroyed tons of supplies that the South badly needed. And about 750 men, women, and children escaped from slavery on nearby plantations. More than one hundred of the men quickly joined the Union army.

The only flaw in her plan, Tubman later said, was her choice in clothing. In the rush to escape, people (and animals) kept stepping on and ripping the end of her dress. “I made up my mind then I would never wear a long dress on another expedition of the kind,” Tubman said.

W

hile escaped slaves were joining the Union army in the South, African Americans in the North were also signing up to fight. In early 1863 the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts became the first African American regiment raised in the North.

hile escaped slaves were joining the Union army in the South, African Americans in the North were also signing up to fight. In early 1863 the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts became the first African American regiment raised in the North.

“Every black man and woman feels a special interest in the success of this regiment,” declared a newspaper called the Anglo-African. The abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass certainly had a special interestâhis sons Lewis and Charles enlisted in the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts.

The soldiers of this new regiment made national headlines in July 1863 when they led an attack on Fort Wagner, a strong Confederate fort on an island in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. Here's what happened.

Just before dark on July 18, the men of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts began marching through the sand leading up to Fort Wagner's walls and guns. The beach was narrow, and some of the soldiers were splashing through ocean water up to their waists. Then the fort's guns exploded with what Lewis Douglass described as “a perfect hail” of bullets and bombs. “Men fell all around me,” Douglass remembered. “How I got out of that fight alive I cannot tell.”

The Union soldiers charged the last hundred yards up to the fort's walls. When twenty-three-year-old Sergeant William Carney reached the wall, he saw the soldier who was carrying the American

flag go down. Carney grabbed the flag and pounced up the sloping fort wall. He was soon shot in the leg, but he stayed up there, waving the stars and stripes. “In this position I remained quite a while,” he said.

flag go down. Carney grabbed the flag and pounced up the sloping fort wall. He was soon shot in the leg, but he stayed up there, waving the stars and stripes. “In this position I remained quite a while,” he said.

When the surviving members of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts were finally forced to retreat, Carney was hit four more timesâin the chest, the right arm, and again in the right leg, and a final bullet grazed his head. Somehow still holding the flag, Carney called to his fellow fighters: “Let us go back to the fort!”

“And the officer in charge said, âSergeant, you have done enough; you are badly wounded â¦' when I replied, âI have only done my duty, the old flag never touched the ground.'”

William Carney

For his actions at Fort Wagner, Carney became the first African American to be awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation's highest military honor.

The skill and bravery of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts finally silenced the people who were still claiming that African Americans would not make good soldiers. And black men continued joining the

armyâmore than 200,000 served in the Union forces by the end of the war.

armyâmore than 200,000 served in the Union forces by the end of the war.

“This year has brought about many changes that at the beginning were or would have been thought impossible,” wrote Christopher Fleetwood at the end of 1863. “The close of the year finds me a soldier for the cause of my race. May God bless the cause, and enable me in the coming year to forward it on.”

I

n the fall of 1863, Abraham Lincoln got his own chance to talk about the cause for which he was fighting. A cemetery dedicated to the Union soldiers who had died in the battle of Gettysburg was about to be opened, and Lincoln was invited say a few words at the opening ceremony. So he took a train to Gettysburg and said a few wordsâand they turned out to be some of the most famous words in American history.

n the fall of 1863, Abraham Lincoln got his own chance to talk about the cause for which he was fighting. A cemetery dedicated to the Union soldiers who had died in the battle of Gettysburg was about to be opened, and Lincoln was invited say a few words at the opening ceremony. So he took a train to Gettysburg and said a few wordsâand they turned out to be some of the most famous words in American history.

In the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln spoke of the big goals the Union was fighting for, like democracy and freedom andâwell, let's just listen to the speech.

“Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before usâthat from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotionâthat we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vainâthat this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address lasted just two minutes. A photographer was racing to set up his camera (which took a long time in those days). By the time he was ready, Lincoln had finished speaking and was back in his chair. After sitting down, Lincoln turned to his bodyguard Ward Lamon. “Lamon,” he said, “that speech â¦

is a flat failure and the people are disappointed.” Many newspapers agreed, calling Lincoln's words “silly” and “flat” and “dull.”

is a flat failure and the people are disappointed.” Many newspapers agreed, calling Lincoln's words “silly” and “flat” and “dull.”

But over the years people have come to appreciate the power and beauty of the Gettysburg Address. In ten carefully crafted sentences, Lincoln presented a bold dream for the future of the United Statesâand for people everywhere. Union soldiers, he said, were fighting for the ideals of freedom and democracy. By winning this war, the Union would prove that democratic government could work. And as a result, freedom would continue to expand, both at home and all over the world.

The night after his speech, Lincoln rode the train back to Washington. Too tired for conversation, he stretched out across several seats with a wet towel over his face. He had explained as clearly as he could what he believed the Union was fighting for. But he had no idea if the Union could actually win.

T

here were more than 10,000 large and small battles in the Civil War. Now we will review all of them.

here were more than 10,000 large and small battles in the Civil War. Now we will review all of them.

Well, maybe not. But we do need to check in on two big fights from late 1863âbattles that helped answer Lincoln's question about whether or not the Union could win this war.

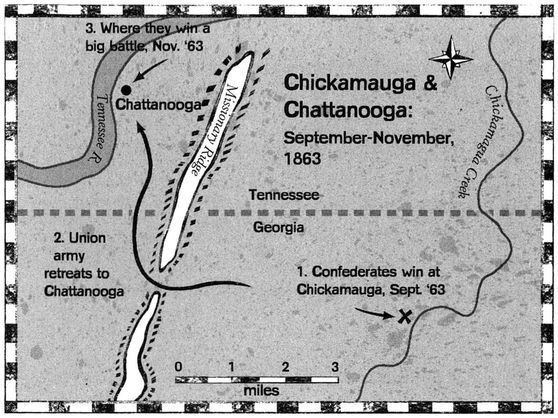

Let's begin at Chickamauga Creek in Georgia. In September about 60,000 Confederate soldiers led by General Braxton Bragg attacked 60,000 Union soldiers under General William Rosecrans. Bragg's forces smashed through the Union lines, sending thousands of Union troopsâincluding General Rosecransâsprinting from the battlefield.

“They have fought their last man, and he is running!” shouted the Confederate general James Longstreet.

Not all the Union soldiers were running away, though. The Union general George Thomas kept thousands of men on the battlefield, fighting until dark. One of the Union “men” who stayed and fought was a twelve-year-old drummer boy named Johnny Clem.

Two years earlier, Johnny had left his home in Ohio and tried to join the Third Ohio Regiment. But the commander, Johnny remembered, “said he wasn't enlisting infants.” Johnny kept trying, and was finally taken on as a drummer boy by a Michigan regiment.

“He was an expert drummer,” said Johnny's sister. “And being a bright, cheery child, soon made his way into the affections of officers and soldiers.”

Johnny may have been “cheery,” but when a bomb destroyed his drum at the battle of Shiloh, he got pretty angry.

“I did not like to stand and be shot at without shooting back.”

So the soldiers gave Johnny his own rifleâfirst sawing off the end of the barrel to make it lighter. And he had this gun with him at the battle of Chickamauga. At one point in the battle, a Confederate officer rode up to him and shouted: “Surrender, you little Yankee!”

Johnny shot the man off his horse and escaped.

The two-day battle of Chickamauga turned into the second-bloodiest battle of the warâsecond only to Gettysburg. Southern soldiers fought their way to a victory that improved the mood of the entire Confederacy. John Jones, who worked for the Confederate government in Richmond, noticed an immediate change on the faces of people in the streets. “This announcement has lifted a heavy load from the spirits of our people,” Jones wrote in his diary. “The effects of this great victory will be electrical.”

Johnny Clem

General Rosecrans's army, meanwhile, retreated north to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Southern forces began surrounding the city.

Other books

Narcissus and Goldmund by Hermann Hesse

The Tailor's Girl by McIntosh, Fiona

Breakwater by Carla Neggers

Murder by Serpents (Five Star First Edition Mystery) by Graham, Barbara

The Second Lady Southvale by SANDRA HEATH

End of an Era by Robert J Sawyer

Biker Chick by Dakota Knight

Satisfaction Guaranteed by Charlene Teglia

Drone Command by Mike Maden

Eternity Swamp by T. C. Tereschak