Two Miserable Presidents (19 page)

Read Two Miserable Presidents Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

What is it like to march into your own nightmare? Union soldiers found out in May 1864, as they moved south into the dark and tangled Virginia forest known as the Wilderness. The year before in this place they had been whipped in the battle of Chancellorsville. Now they were marching past the remains of soldiers killed in that fight: twisted skeletons and white skulls that seemed to be staring up at them. Union soldiers knew they were about to face another big battle in these spooky woodsâand they had a bad, bad feeling about it.

I

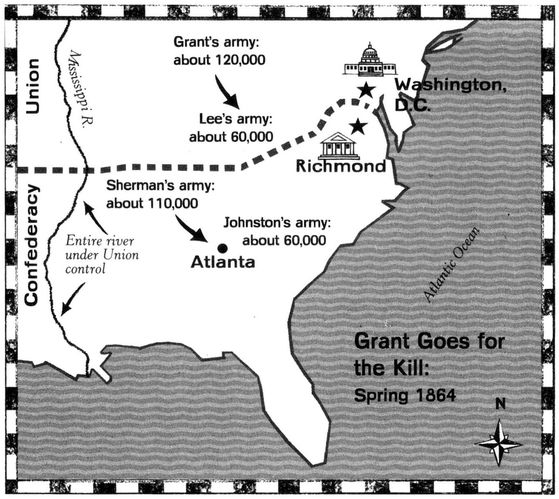

n the spring of 1864 there were two main Confederate armies. One was in Virginia, under the command of Robert E. Lee. The other, in Georgia, was led by Joseph Johnston. Grant decided to attack both of these armies at the same time.

n the spring of 1864 there were two main Confederate armies. One was in Virginia, under the command of Robert E. Lee. The other, in Georgia, was led by Joseph Johnston. Grant decided to attack both of these armies at the same time.

The Union general William Tecumseh Sherman described Grant's plan like this:

“He was to go for Lee and I was to go for Joe Johnston. That was his plan.”

William Tecumseh Sherman

Okay, so it wasn't a fancy plan. But Grant knew that he and Sherman had twice as many soldiers as Lee and Johnston. Grant's strategy was to use this advantage to “hammer continuously against the armed force of the enemy.” He was convinced that the larger Union forces could pound their way to victory.

But could Union forces win a big victory before the presidential election in November? If not, Lincoln was going to loseâand the South would gain its independence.

The future of the United States would be decided on the battlefield in the next few months.

T

hat explains why Grant stuffed so many cigars into the pockets of his pants and jacket before leaving his tent each morningâchewâing and smoking cigars helped him handle the terrible pressure he was under.

hat explains why Grant stuffed so many cigars into the pockets of his pants and jacket before leaving his tent each morningâchewâing and smoking cigars helped him handle the terrible pressure he was under.

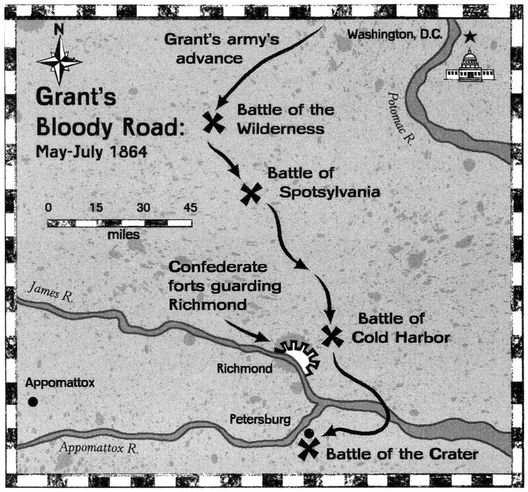

Grant began his part of the plan by leading his army south into Virginia in early May 1864. While Union troops were tripping through the heavily wooded Wilderness, Lee's army attacked. This sparked one of the war's most confusing battlesâand that's saying something.

“No one could see the fight fifty feet from him,” said the Union soldier Warren Goss. “It was a blind and bloody hunt to the death.”

Men on both sides were ordered to charge at the enemy. Slight problem: no one could see the enemy through the twisted bushes and vines and trees. The only way to find the enemy was to stumble forward and crash into him. After being shot in the leg and captured, one Texas soldier shouted, “You Yanks don't call this a battle, do you? Our two armies ain't nothing but howling mobs!”

Thorns ripped soldiers' clothes and sliced their skin as they drove each other through the woods. Exploding bombs set trees on fire, and the wind blew smoke and unbearable heat back and forth across the battlefield. “The men fought the enemy and the flames at the same time,” Warren Goss remembered. “Their hair and beards were singed and their faces blistered.”

Grant spent most of the battle of the Wilderness sitting on a log, listening to reports from his officers and puffing cigars so furiously that his head disappeared in a cloud of yellow smoke. He went through twenty cigars in one day (a personal record), and with good reasonâlike every other Union general who had marched into Virginia, Grant was taking a whipping from Robert E. Lee. Grant's forces suffered more than 17,000 casualties in the Wilderness, compared to about 8,000 for Lee's army.

Grant was off to a terrible start.

W

hen the Wilderness fighting ended, Grant walked into his tent and collapsed face-first on his cot. Some witnesses said he burst into tears. Others said he just took a nap. Either way, by the time he came back outside, he had made a major decision.

hen the Wilderness fighting ended, Grant walked into his tent and collapsed face-first on his cot. Some witnesses said he burst into tears. Others said he just took a nap. Either way, by the time he came back outside, he had made a major decision.

Grant ordered his army to pack up and prepare to move. Here we go again, thought discouraged Union soldiers. Every year so far

they had marched into Virginia, fought Lee's army, lost, and retreated back to the North.

they had marched into Virginia, fought Lee's army, lost, and retreated back to the North.

But as this march began, the men noticed that they weren't heading north. They were marching farther south. They were continuing their drive toward Richmond.

“Our spirits rose,” said a Union soldier. “The men began to sing.”

A newspaper reporter asked Grant if he had any message for Abraham Lincoln. Yes, Grant said: “If you see the president, tell him, from me, that whatever happens there will be no turning back.”

R

obert E. Lee was not surprised. “General Grant will not retreat,” Lee predicted after the battle of the Wilderness. “He will move to Spotsylvania.”

obert E. Lee was not surprised. “General Grant will not retreat,” Lee predicted after the battle of the Wilderness. “He will move to Spotsylvania.”

Lee rushed his soldiers south to Spotsylvaniaâand got there just in time to prepare for another massive attack by Grant's army. At first Union soldiers started gaining ground. Lee rode to the front of his army and prepared to lead a charge himself.

But his men refused to budge. Southern soldiers would do anything for General Leeâexcept allow him to get shot.

“General Lee to the rear!” someone shouted.

Then all the soldiers, young men who had never given an order in their lives, were suddenly bossing around their commander. “General Lee to the rear!” they yelled. “General Lee to the rear!”

Lee replied: “If you will promise me to drive those people from our works, I will go back!”

The men cheered in agreement. Then they charged forward, and drove “those people” back.

The battle of Spotsylvania raged on day after day, and soldiers who had seen years of combat said it was the most terrifying battle yet. The two armies blasted and stabbed at each other from just a few feet away, while rain poured down and wounded men slowly sank into the bloody mud. “I never expect to be fully believed when I tell what I saw of the horrors at Spotsylvania,” said a Union officer.

After a week of these horrors, Grant called off the attack. Once again, he had lost far more men than Lee. And once again, he packed up and moved his army south. One more big attack, Grant thought, and he could smash his way through to Richmond. “Lee's army is really whipped,” Grant said.

He had never been more wrong in his life.

W

hile walking through camp on the night of June 2, a Union officer noticed something very strange:

hile walking through camp on the night of June 2, a Union officer noticed something very strange:

“The men were calmly writing their names and home addresses on slips of paper and pinning them on the backs of their coats, so that their bodies might be recognized and their fate made known to their families at home.”

Horace Porter

Grant's men were camped at a place called Cold Harbor. Their orders were to attack Lee's army before sunrise. Grant was confident this attack would succeedâbut his soldiers seemed to know better. They knew Lee was out there, ready and waiting for them.

One young soldier actually skipped ahead one day in his diary and wrote: “June 3, 1864. Cold Harbor. I was killed.”

The Union attack began at four-thirty the next morning. “We started with a yell,” said a Massachusetts soldier named Harvey Clark.

“To your guns, boysâthey're charging!” shouted Southern soldiers.

Harvey Clark was one of about 60,000 Union men charging right toward those gunsâand the entire army slammed face-first into what Clark described as a “solid sheet of fire.”

“It seemed more like a volcanic blast than a battle,” said another Union soldier.

Nearly 8,000 Union soldiers were shot, most of them in the first ten minutes of fighting. “The dead covered five acres of ground about as thickly as they could be laid,” a Confederate officer later said. Among the dead was the soldier who had predicted his own death in his diary the night before.

“I regret this assault more than any one I have ever ordered,” Grant told his officers that night.

He was even more depressed when he read what Northern newspapers were saying about him now. “They call me a butcher,” Grant grumbled.

S

o let's review: Grant's plan was a miserable, bloody disaster. Except for one small detail: it was working.

o let's review: Grant's plan was a miserable, bloody disaster. Except for one small detail: it was working.

Even after the slaughter at Cold Harbor, Grant continued fighting his way south. New soldiers arrived from the North, so Grant's army was still twice as large as Lee's. And by the end of June, Grant had Lee's army nearly surrounded in the town of Petersburg, just twenty-five miles from Richmond.

Meanwhile, down in Georgia, General William T. Sherman pushed Confederate forces all the way to the edge of Atlanta. Home to weapons factories and key railroad lines, Atlanta was a city the South simply could not afford to lose.

Now it was all a question of timing. As the summer sped past, Sherman tried to fight his way into Atlanta. And Grant was still stuck

outside of Petersburg. The Union needed a big victory, and the clock was ticking.

outside of Petersburg. The Union needed a big victory, and the clock was ticking.

Not that Southern soldiers were enjoying the summer. In Petersburg, Lee's soldiers were living in filthy trenches, in constant danger from Union bullets and bombs. Food shortages got so bad that the men were regularly given bags of rotting corn filled with squirming worms. One soldier remembered the men getting hunks of bacon that were “scaly” and “spotted” and gave off “a stinking smell when boiled. You could put a piece in your mouth and chew it for a long time, and the longer you chewed it the bigger it got. Then, by desperate effort, you would gulp it down.”

The South was running out of food. But the North was running out of time.

Other books

Shades of War by Dara Harper

The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ by Philip Pullman

Line of Scrimmage: A Secret Baby Sports Romance (Pass To Win Book 2) by Roxy Sinclaire

Whirlwind Love: Libby's Journey by Hendley, DiDi

Front Man by Bell, Adora

El origen de las especies by Charles Darwin

Henry VIII's Health in a Nutshell by Kyra Cornelius Kramer

Wake Up Now by Stephan Bodian

The Protected (Fbi Psychics) by Walker, Shiloh

Flower Girl Bride by Dana Corbit