Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (126 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

We Had Security Issues

After picking up Kevin’s brother, Sean, who lives downtown, and driving for what seemed like four hours to find a grocery store to stock up on tailgate brats and beers for the pregame celebration, we drove into the lots at Chavez Ravine, paid nearly half a year’s salary to park the road trip mobile, and licked our chops at the tailgating nirvana that certainly lay before us.

“With all this parking, there must be every kind of tailgate sport imaginable,” Josh predicted.

“Roller-skiing,” Kevin shouted.

“Pool diving!” Sean answered back.

“Naked mud wrestling!” Josh shouted, prompting Kevin and Sean to exchange a confused glance.

After we parked, Josh pulled the hibachi out of the trunk. Kevin laid open the cooler, which was filled to the brim with beers and ice, and we set up our chairs. It was 11 a.m. and the game didn’t begin until 1:35 p.m. We had

more than two and a half hours of blue tailgating heaven before us.

Or so we thought.

Not three minutes after cracking our first beer, a police officer pulled up behind us, pinning the road trip car into its spot with its heavy bumper. Two officers stepped out of the cruiser who bore a striking resemblance to Judge Reinhold and the bald cop from the movie

Beverly Hills Cop.

“Gentlemen, how are we this morning?” said Reinhold.

“All right, Hamilton,” said Kevin.

“What do you think you’re doing with the beer?”

“Drinking it,” said Sean. “You want us to throw a couple of brats on for you?”

“No, sir,” said Bald Cop.

“Ah, a ribs man,” said Josh, dumping briquettes into the hibachi. “I’ll put you each down for a couple.”

“Gentlemen,” said Reinhold sternly, “I’m afraid we have ourselves a situation here.”

“A situation,” said Josh trembling, dropping the bag of briquettes. “What kind of situation? Kevin, what does he mean by

situation?

”

“I mean there’s no tailgating at Dodger Stadium,” said bald cop.

“Really?” said Sean.

“Really,” said Reinhold.

“But that’s such a waste of all this great parking,” said Kevin.

“Be that as it may,” said Bald Cop, “You all need to come with us to the police holding facility inside the stadium.”

“But we didn’t know,” said Sean. “These guys are from out of town.”

Sports in the City

Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum

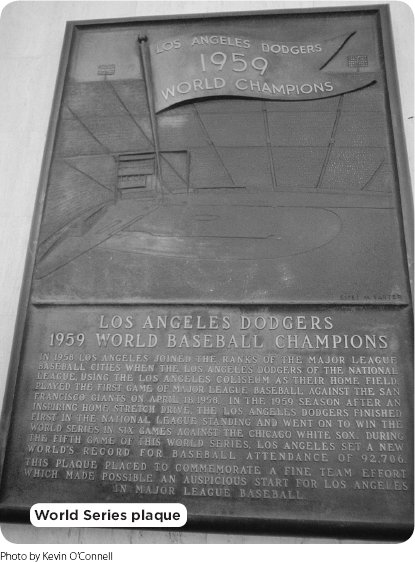

We received better access to this facility than we did to Dodger Stadium. The coliseum has been home to two Olympics and hosted the first World Series in L.A. history. The familiar arched entryway is adorned with statues of male and female athletes, as well as large bronze plaques commemorating the many great events held there. Still, it was an ugly place for baseball.

“I’m sorry about that gentlemen, but rules are rules.”

“Shoot,” said Josh. “We’re going to jail.” And he began to put the bricks back into the bag one-by-one as quickly as his hands would move.

“Listen officer,” said Sean, working some of his best LA charm. “It was an innocent mistake. Could we pay some sort of fine, or something?”

“We haven’t had more than a sip,” said Kevin.

Reinhold looked us over carefully. There were no empty beer cans anywhere around the car. “I suppose if you dumped the open containers, we could let you off with a citation.”

“A citation!” Josh said, raising his voice.

“That sounds perfect,” said Kevin, dumping his own beer onto the black top and dumping Josh’s out as well. When the cans were empty, Kevin said, “By the way, officer. Where could we set up our tailgate?”

“Anywhere but here,” said Bald Cop, looking up from his writing of a very steep ticket and pointing to the fence.

Once the cop ripped the ticket from his pad, Kevin looked it over and said, “I guess we’ll be sitting in the bleachers when we get to Petco.”

As the cops left, we continued packing everything back into the road trip mobile.

“Well,” said Josh, “what do we do now? Waste all this beautiful tailgating sun, or waste our money parking?”

“Don’t worry gentlemen,” said Sean. “I think I have a way to preserve both.” We finished packing up the car and pulled it to the very last spot in the lot, but still inside the gates. Then we carried our hibachi, cooler, and lawn chairs directly outside the gate and set up on the sidewalk. Across the street from us, in plain view, stood the LA Police Academy.

When the hibachi heated up, Kevin tossed some cased meat on and said, “I love the smell of brats, especially in front of the Police Academy … smells like … Victory.”

Josh was flummoxed. “You mean we can tailgate here, in front of the LA Police Academy,

*

but not inside the stadium parking lot?” Josh asked. “I’ll never understand the West Coast.”

SEATTLE MARINERS,

SEATTLE MARINERS,SAFECO FIELD

A Shining Jewel in the Emerald City

S

EATTLE

, W

ASHINGTON

680 MILES TO SAN FRANCISCO

960 MILES TO LOS ANGELES

1,330 MILES TO DENVER

1,385 MILES TO MINNEAPOLIS

G

rowing up in Western Washington, Kevin, along with the rest of the region’s fans, had no hometown hardball team to call his own. After losing the Seattle Pilots after a single season to some used car dealer from Milwaukee by the name of Bud Selig, all hope for a regional franchise appeared lost. Then, magically, in 1977 his prayers were answered when Major League Baseball added Seattle and Toronto to the American League. Like all baseball fans in the Pacific Northwest, Kevin was elated. Seattle would have its own team, and it was an expansion team, which meant it wouldn’t be breaking the hearts of countless fans of another city, the way Bud Selig had done to so many when he stole the Pilots. But there was a catch. Along with the Seattle Seahawks of the NFL, the Mariners intended to play their home games at the Kingdome. Indoor baseball? Though it wasn’t ideal, Kevin tried his best to embrace it, since it was certainly a far superior alternative to having no baseball to watch at all.

The Mariners truly were awful from the start. It took them fifteen seasons to post a winning record, and their uniforms rivaled the Astros and Padres for worst in baseball. Perhaps the funniest thing of all about the hapless M’s—who couldn’t seem to get much of anything right—was their home stadium, the Kingdome, named after King County, in which Seattle resides. While the venue was enjoyed as a place to escape the rainy fall and winter weather during football season, and while Kevin saw the Monsters of Rock tour there in 1988 and, perhaps, most importantly the Seattle SuperSonics (formerly of the NBA) win the city’s only major championship there, the game of baseball suffered in the dome.

Grass, as we all should know, doesn’t grow well without sunlight, so the Kingdome sported artificial turf that looked about as real as the grass in the Brady Bunch’s backyard, covered by a concrete roof that looked like a gigantic orange juicer. Still, Kevin stuck by his hometown team. Like millions of other Seattleites, he never gave up hope that outdoor baseball might return to the Pacific Northwest, even as Mariners ownership threatened to move the team out of the city during the early 1990s.

Many point to the Mariners’ playoff run of 1995—now commonly referred to as “the season that saved baseball in Seattle,” as having played a major role in bringing about the baseball renaissance in the city. The M’s inspired playoff run also did well by hardball fans all around the Majors who were frustrated by the strike-shortened seasons of 1994 and 1995. Some would say that the Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa battle for home run supremacy was what brought fans back. But the fact is that both of those men, rightly or wrongly, have the taint of performance-enhancing drugs on their records, and when people remember that battle that seemed so epic at the time, in truth, it leaves them feeling ripped off.

Not so with the Mariners and their inspiring playoff run of 1995. In the afterglow of that magical year, plans were made to leave the Kingdome to football and monster truck rallies, and for the Mariners to build a new future for themselves. A future where the team would continue its recently found competitive ways. A future with uniforms that didn’t look like they should be worn on Halloween. And, perhaps most exciting of all to hardball fans in the Northwest, a future where the game would be played in a baseball-only park that the team’s growing fan base could be proud of. A park that would combine the charm of the classic older parks with all of the latest amenities—beneath a ginormous retractable roof big enough to land the space shuttle under.

By all counts, “the Safe” has delivered this promised future in spades. When Kevin first laid eyes on Safeco’s green grass and rust-colored dirt, and looked up to see the Seattle skyline set against a perfect blue horizon, he wept with joy. Literally, he cried.

Josh:

But you cried at the end of

Toy Story 3

, too.

Kevin:

Every toy had a purpose again. It was beautiful and symbolic.

Making Safeco a reality was no small task given the local economic climate in the mid-1990s and voters of the Pacific Northwest routinely voicing their displeasure with the idea of using public money to support private industry. A bill to increase the sales tax by .01 percent was voted down by King County voters in September 1995. However, city and county officials recognized that the small margin of defeat of the proposition meant a good number of folks would likely vote against them in upcoming elections. If the Mariners left town under these officials’ collective watch because a new ballpark could not be secured, well, proverbial political hay could be made of it. Or maybe all these elected officials quickly became loyal Mariner fans overnight. We’re not sure which. At any rate, not long after, a financing package for Safeco Field was adopted that included hotel, rental car, and restaurant tax increases, ballpark admissions taxes, the selling of Mariner license plates, and scratch-ticket lottery games. One lottery game was called “My-Oh-My,” named for a catchphrase of the late Dave Niehaus, the Mariners’ colorful commentator. After this financial stake was driven into the ground, the Safeco Insurance Company shelled out $40 million for the naming rights to the park.

Josh:

I bet you bought a zillion of those Niehaus scratch-offs.

Kevin:

Sure, I did. I had to support the team.

More than thirty thousand fans came out to cheer on Ken Griffey Jr. as he slapped on a pair of work gloves and partook in Safeco’s ceremonial groundbreaking on March 8, 1997. From groundbreaking until the ballpark officially opened for play more than two years later, a webcam provided fans with continuous coverage of Safeco’s construction site.

Safeco’s most distinctive feature is without doubt its remarkable retractable roof. It provides, in our opinion, the penultimate example of a how a retractable roofed stadium should be built. From the street behind Safeco, the roof of the building looks postindustrial. While from the street out front, the Safe’s brick facade provides a classic ballpark feel. But unlike other retractable roofs that have been built in baseball, Safeco’s roof covers but does not enclose the field, which allows wind to whip through, and preserves an open-air playing environment. The massive roof sections are supported by trusses on wheels, and actually rest on elevated tracks that were built much higher than they needed to be. The reason for all this is that it gives the feeling that baseball is being played beneath an enormous umbrella, rather than indoors. Whether the roof is open or closed, baseball at Safeco always feels as if it’s being played outside, which enhances the game-day experience over the Kingdome tremendously.

The roof’s three independently moving panels span nine acres, weigh twenty-two million pounds, and contain enough steel to build a fifty-five-story skyscraper. The lid is capable of withstanding seven feet of snow and seventy-mile-per-hour winds. During Safeco’s first few weeks there were frequently reported mechanical errors that caused the roof to open and close unexpectedly. These early kinks have since been ironed out. The roof’s arching support trusses are “in play,” provided the ball hits a truss in fair territory and comes down in fair territory. To date, this has yet to occur, but there have been two occasions where the trusses were hit by balls in foul territory, which makes some sense because they are much closer to the playing surface as they arch down toward the ground.

The roof is certainly an engineering marvel. In many ways it set the standard for what a retractable roof at a ballpark should be. But there were other technological implementations innovative to Safeco that have since been copied by other ballparks, too. The playing field

itself is capable of absorbing twenty-five inches of rain in twenty-four hours, thanks to a layering of sand, pea gravel, and genetically engineered grass, combined with underground heating and drainage systems.

Josh:

Kind of overkill, considering Safeco has a roof, don’t you think?

Kevin:

Perception is reality. And the perception that the game will never be cancelled, ever, rules at Safeco.

Interestingly enough for meteorologists and baseball geeks like us, even though Safeco’s umbrella protects its fans from the legendary rains, it does little to protect them from the cool winds that can come off Puget Sound. The left-field bleachers are particularly exposed on cold and windy days—which, let’s face it, in Seattle is about three-quarters of the summer. And the center-field bleachers only fare a bit better, getting a bit of wind blockage from the centerfield scoreboard.

A bit of irony for Seattle ball fans … Safeco opened not to too much rain, but too much sun. The open-air feel also allowed for the rays of the setting sun in the west over the Olympic Mountains (which are a beautiful backdrop from much of the park) to stream in and cause problems for hitters as it reflected off the batter’s eye. The Mariners were able to solve the problem early on by constructing a series of screens that protected the batter’s eye and the eyes of the corresponding batters. However, rosy fingered sunsets still tickle at the eyes of fans, in the orange and purple gloaming.

Most parks make their debut on Opening Day. But did we mention that this city and franchise don’t usually care much for convention? The Safe opened on July 15th, midway through the 1999 season, with a 3–2 Mariners loss to their supposed interleague rivals, the San Diego Padres. Once fully established in their new home, the Mariners captured consecutive American League West titles in 2000 and 2001 and tied the MLB record for the most wins in a season with a blistering 116 in 2001. Unfortunately, though, the M’s lost to the Yankees in the American League playoffs both years. The fact that the Mariners have never even been to the World Series—even while newer baseball arrivals like the Florida Marlins, Tampa Bay Rays, Arizona Diamondbacks, and Colorado Rockies have—actually staggers the mind.

Kevin:

Not even when we had A-Rod, Junior, Jay Buhner, Edgar Martinez, and Randy Johnson. Not to mention Lou Piniella managing. Sheesh.

Josh:

Your guys blew it!

Though it did little to enhance a ballgame, the Kingdome still holds more than its share of Mariners history, both for the good, and what has passed as standard operating procedure in Seattle baseball, the hapless. One part they got right was when they blew the place up. The demolition, on March 26, 2000, was streamed live on the Internet, allowing multitudes worldwide to watch the implosion of the “Concrete Goiter,” as it was not-so-affectionately called by some locals. The structure that was “built to last a thousand years” came down after twenty-three, and in just 16.8 seconds. Up until the time of its demolition, the Kingdome boasted the largest thin-shell concrete-domed roof in the world. No ball ever hit the roof, though players in batting practice constantly tried. On two occasions balls went up and never came down—in 1979 a ball hit by the Mariners’ Ruppert Jones, and in 1983 a ball hit by Milwaukee’s Ricky Nelson. Both got stuck in the sound system speakers and were ruled foul.

While the Jones and Nelson balls never fell to earth, fifteen-pound tiles from the roof did in 1994, necessitating repairs that sent the M’s on an extended road trip for the last month of the strike-shortened season.

Before achieving their first winning season in 1991, the Mariners had posted a sub-.500 record in each of their first fourteen campaigns. They were often considered a laughingstock around the league and the butt of jokes on late-night TV. During their many lean years, the Mariners, not unlike the Triple A team they acted like, had to be creative to get people to come to their stadium. In 1983 the USS

Mariner

was launched behind the left-field fence. The sloop was a gold-colored boat that would rise up and fire a cannon blast for Mariner wins and every time an M’s batter hit a home run. Another gimmick was the Bullpen Tug, which ferried relievers to the mound from the bullpens the Kingdome never had. Fence distances were measured in fathoms alongside the more traditional feet. And for home runs and wins, another Mariner innovation, indoor fireworks, exploded near the roof of the Dome.