Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (46 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Elevated vascular endothelial growth factor (VGEF) occurs in two-thirds of patients.

Treatment of the myeloma component in the usual way often helps the other manifestations. Local bone lesions often respond to radiotherapy. Progressive peripheral neuropathy to respiratory failure over years is the natural history.

Bone marrow (haematopoietic cell) transplantation

Bone marrow transplantation is being performed for an increasing number of indications. Patients are chronically ill and often available for examinations. Two groups of patients are treated in this way: those with a malignant condition (

Table 8.21

), who have their bone marrow destroyed by irradiation or chemotherapy given in marrow-toxic doses to treat a malignancy; and those with a defective bone marrow that is destroyed and then replaced (

Table 8.22

). Autologous transplants (when the patient’s own marrow or stem cells are stored and then reinfused) are now more common than allogenic transplants (when another person is used as the donor of marrow or stem cells).

Table 8.21

Malignant indications for bone marrow transplant

| CONDITION | AUTOLOGOUS | ALLOGENIC |

| Acute leukaemia | Yes (uncommon) | Yes |

| Chronic myeloid leukaemia | Yes (rare) | Yes (uncommon now except in TKI failure) |

| Lymphoma | Yes (common) | Yes |

| Hodgkin’s disease | Yes (common) | Yes |

| Carcinoma of the breast | No | No |

| Carcinoma of the testis | Yes | No |

| Multiple myeloma | Yes | Yes |

| Wilm’s tumour | Yes | No |

Table 8.22

Non-malignant indications for bone marrow transplant

| CONDITION | AUTOLOGOUS | ALLOGENIC |

| Aplastic anaemia | No | Yes |

| Sickle cell disease | No | Yes |

| Thalassaemia | No | Yes |

| Gaucher’s disease | No | Yes |

| Severe combined immunodeficiency | No | Yes |

| Fanconi’s anaemia | No | Yes |

| Autoimmune disease (RhA, Multiple sclerosis) | Yes | No |

The history

1.

Ask what the indication for the transplant was.

2.

Find out whether there has been a problem leading to the current admission to hospital (if the patient is an inpatient).

3.

Ask whether other treatment has been tried unsuccessfully. (For example, bone marrow transplant is often the treatment of choice for relapse after treatment for leukaemia or lymphoma.)

4.

Find out whether the bone marrow transplant was autologous or allogenic. How was the marrow ablated before transplant (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or both) and, if the transplant was autologous, how were the stem cells harvested (from peripheral blood or by bone marrow aspiration)?

5.

If the transplant was allogenic, does the patient know the donor? Only about 30% of people have an HLA-compatible relative. For the rest, a volunteer unrelated donor is used. HLA antigens are inherited together and rarely cross over. The patient may know how close the match was.

6.

Ask how long the patient was in hospital after transplantation. (Engraftment is usually quicker and complications fewer after autologous transplant.) Ask specifically about problems with infection in the early period and how complications were managed.

7.

Find out what effects this complicated illness and treatment have had on the patient’s life and ability to work. Ask about family and financial problems. Young patients are likely to have been made sterile by the treatment. Total body irradiation and the use of alkylating agents are more likely to cause permanent sterility than other treatments. Women more often regain fertility than men. Ask tactfully whether the patient is aware of this.

8.

Ask how effective the treatment has been. Does the patient feel better or worse than before and what medium- and long-term prognosis has he or she been given?

9.

Ask whether there have been specific transplant-associated problems. Ask specifically about the symptoms and signs of graft versus host disease (GVHD) and the other complications of allogenic transplantation (

Table 8.23

).

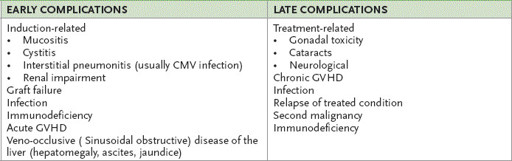

TABLE 8.23

Complications of allogenic bone marrow transplant

10.

Ask about the patient’s current medications.

The examination

Examine for persisting or recurrent signs of the condition for which the bone marrow transplant was performed.

1.

Examine for signs of GVHD. These include skin changes similar to those of scleroderma, dry eyes and mouth (sicca syndrome), alopecia and bronchiolitis obliterans (signs of airflow obstruction).

2.

Examine for hepatic enlargement and ascites (veno-occlusive disease of the liver). Feel all the lymph node groups (e.g. enlarged as a result of a second malignancy, such as ALL or melanoma) and examine the eyes (e.g. secondary glioblastoma).

3.

Look for signs of infection in the lungs and for herpes zoster.

4.

Examine the hips (aseptic osteonecrosis).

5.

Patients who have had radiotherapy may show evidence of hypothyroidism.

Management

Detailed discussion about methods of transplantation will not be required.

1.

Management after transplant begins with supportive treatment to prevent infection and bleeding before engraftment occurs. Platelet and blood transfusions may be required and the patient is usually kept isolated. Transfused products are irradiated to prevent GVHD from transfused lymphocytes. Most patients receive colony-stimulating factors to speed recovery. Platelet recovery is usually the slowest and tends to determine the time of discharge from hospital.

2.

Patients who have had an allogenic transplant are at risk of GVHD. This risk is reduced if the HLA match is a good one (only one locus is mismatched). Prophylaxis against GVHD with some combination of prednisone, methotrexate and cyclosporin is usual. The donor marrow may be treated to remove T cells to reduce the incidence of GVHD, but this increases the risk of graft rejection. The risk of GVHD is also increased by previous exposure to blood products and by previous pregnancy.

3.

Acute GVHD can occur even when the major HLA antigens match. It occurs by definition in the first 3 months after transplant and is characterised by diarrhoea, skin rash and liver function test changes. Severe acute GVHD (generalised erythroderma or desquamation) reduces survival and requires aggressive treatment. It is usually treated with high doses of prednisone, antithymocyte globulin and monoclonal antibodies to T cells. Some centres use prophylactic treatment after transplant with methotrexate

and tacrolimus or cyclosporin. Remember that the presence of some GVHD reduces the risk of tumour recurrence as a result of graft versus tumour activity.

4.

Chronic GVHD develops after 3 months and affects up to half of transplant recipients. Patients develop an autoimmune-like illness with sicca syndrome, arthritis, cholestasis and bronchiolitis obliterans. It is treated with immunosuppression. It is rare for it to persist for more than 3 years.

5.

Infection can be a problem at various times after transplant. Bacterial infection is most common during the early period before the neutrophil count reaches normal levels. It is treated with isolation and appropriate antibiotics. Fungal infection can become a problem within a week of transplant but usually resolves once engraftment has occurred.

Pneumocystis jirovecci

infection and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection can occur within a week of transplant but are uncommon after 3 months. Interstitial pneumonitis occurs in up to 10% of patients. This is usually the result of CMV infection and is treated with supporting measures and ganciclovir. CMV-negative recipients should receive only CMV-negative blood products, and CMV-positive patients should receive prophylactic ganciclovir. Prophylactic treatment with fluconazole, cotrimoxazole and ganciclovir is often used to prevent these problems.

6.

Graft rejection is usually a result of the activity of functional host lymphocytes and is most common in patients who have not had their marrow ablated (e.g. those with aplastic anaemia).

7.

Recurrence of leukaemia may be treated with infusion of more donor T cells, although this increases GVHD.

8.

Veno-occlusive disease of the liver occurs in up to 50% of patients. Most recover, but in severe cases treatment with tissue plasminogen activator may be indicated. The use of ursodeoxycholic acid may also diminish the incidence.

9.

Overall, autologous bone marrow transplant is associated with similar but less severe complications. GVHD, however, does not occur. Transplant-related mortality is much less at 1–2%.

10.

The prognosis varies with the indication for the treatment (

Table 8.24

). In general, malignant conditions have a better prognosis when treated with bone marrow transplant as a primary or secondary therapy than when it is used only after all else has failed. Patients with non-malignant conditions can often be very successfully treated with bone marrow transplant. For example, aplastic anaemia patients can expect up to 90% disease-free survival. Opinions differ about the use of bone marrow transplant as initial treatment for these patients.

Table 8.24

Survival of bone marrow transplant patients

| CONDITION | 5-YEAR SURVIVAL RATE |

| Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) | 50% |

| Acute lymphatic leukaemia (ALL) | 50% |

| Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), chronic phase | 70% |

| CML accelerated | 40% |

| CML blast crisis | 15% |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) | 50% |

| Hodgkin’s disease | 50% |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 40% |

| Aplastic anaemia | 90% |

| Severe combined immunodeficiency | 90% |

| Thalassaemia | 90% |

11.

Remember that, as with any complicated and life-threatening illness, pay great attention to the patient’s ability to cope and the availability of support at home; these are important matters you must be able to discuss.

CHAPTER 9

The rheumatological long case

It’s better to be dead, or even perfectly well, than to suffer from the wrong affliction.

Ogden Nash (1902–71)

Joint and mobility problems are common in long case patients, even when this is not the central abnormality. Elderly and obese patients often have osteoarthritis, which limits their ability to exercise and lose weight. A modified GALS (gait, arms, legs and spine) assessment can be a quick way to identify the importance of these matters to the patient (and to the long case itself).

Ask:

1.

Have you been troubled by pain or stiffness in your back or muscles or joints? Where?

2.

How are you affected by this? Can you walk up and down stairs? Can you get out of a chair easily? Can you dress and wash yourself?

Examine:

1.

Gait