Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (44 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Prognosis

This depends on the stage, disease bulk, age and performance status In general, in:

•

stage I, expect 85–95% 10 years disease-free survival

•

stage II, expect 80–90% 10 years disease-free survival

•

stage III and IV, expect 60% 10 years disease-free survival.

Complications of treatment

1.

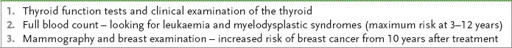

The improvement in survival achieved with current treatment means that complications of treatment are more likely to cause death than the disease. Routine annual testing and review is recommended (

Table 8.16

).

Table 8.16

Routine annual tests for patients treated for Hodgkin’s disease

2.

Secondary malignancies, including leukaemia and carcinomas, are associated with the use of alkylating agents.

3.

Breast cancer risk is associated with chest irradiation.

4.

Chest radiotherapy also increases the risk of coronary artery disease after 10 years or more, and of hypothyroidism.

5.

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy increase the risk of carcinoma of the lung, which is significantly greater again for smokers.

6.

Infertility can occur in men and women treated with chemotherapy. The chance of recovery of fertility is much greater for young patients. Sperm or ovarian tissue banking may be offered to patients.

NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA

Prognosis and treatment depend mainly on the histological type (particularly whether it is nodular or diffuse and based on the International Working Formulation – see

Table 8.13

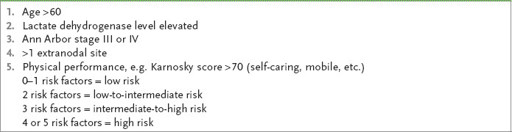

); most cases of low-grade lymphomas are stage III or IV at presentation and require only observation if asymptomatic. The International Prognostic Index (

Table 8.17

) has proved an accurate way of assessing the patient’s likely course. More recently, treatment decisions have been based on the WHO classification (

Table 8.12

).

Table 8.17

International Prognostic Index – clinical risk factors for a poor outcome

Treatment protocols: International Working Formulation classification

1.

Low-grade lymphoma

. These are not curable and treatment does not increase survival. Follicular mixed cleaved cell low-grade lymphoma is indolent. Commonly it presents as stage IVA.

a.

For asymptomatic low-grade lymphoma no treatment is indicated.

b.

For symptomatic low-grade lymphoma, chlorambucil with or without prednisone, or CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone), is the usual initial treatment.

For stages I and II low-grade lymphoma (uncommon), extended field radiation may be used in younger patients with curative intent, but they must be very carefully staged first. More aggressive regimens (as for intermediate-grade) may produce more complete remissions, but have not been shown to increase survival. Maintenance single-agent chemotherapy has not reduced the relapse rate.

2.

Intermediate and high-grade lymphoma

. These have a poor prognosis if untreated. Diffuse large cell lymphoma and high-grade lymphomas are potentially curable with treatment.

a.

Stage I and some stage II: aggressive treatment to try for cure is essential, but careful staging must be carried out first. A combination of immunochemotherapy (e.g. rituximab plus CHOP–RCHOP) and radiotherapy is often used.

b.

Stages II, III and IV:

i.

diffuse large cell lymphoma – combination chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine and prednisone); high-dose methotrexate and intrathecal methotrexate may be added if indicated

ii.

diffuse well-differentiated lymphocytic lymphoma – this is the most indolent type and prognosis is indistinguishable from that for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; no treatment is required unless symptomatic

iii.

other diffuse types: combination chemotherapy

iv.

salvage chemotherapy – failure of remission or relapse is an indication of a poor prognosis; salvage treatment is usually attempted with drugs such as cisplatin or cytosine arabinoside, but remission rates are only 20–30%. Autologous stem cell transplantation may be indicated in this setting.

c.

AIDS-related lymphomas: these tumours tend to be of the large B cell or Burkitt’s type and very aggressive. Results of combination chemotherapy, so far, have been poor.

The best regimens, using central nervous system prophylaxis, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) (to limit neutropenia) and a modified chemotherapeutic combination, have produced 50% complete response rates. There is a high mortality from associated infection in these immunodeficient patients. Rituximab improves results and it is also imperative to treat concurrently with antiviral therapy.

Treatment protocols: WHO classification

1.

Precursor B cell neoplasms

. Precursor B cell lymphoblastic leukaemia/ lymphoma is usually the childhood malignancy acute lymphocytic leukaemia (ALL). The lymphoma is rare in adults and rapidly progresses to become leukaemia. Combination chemotherapy is used to induce remission and continuing treatment to attempt cure. The cure rate in adults is about 50%.

2.

Mature B cell neoplasms

. B cell chronic lymphoid leukaemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma is the most common lymphoid leukaemia and represents about 75% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Patients with only bone marrow involvement and lymphocytosis are not usually treated. They have a median survival of more than 10 years. Once liver and splenic involvement have occurred, treatment is likely to be required at some stage, but may not be recommended until bone marrow failure is present. Oral chlorambucil or the more potent intravenous drug, fludarabine, often combined with rituximab, is most often recommended. Young patients may benefit from bone marrow transplant.

3.

MALT-type lymphoma (extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma – 8%)

. These gastric mucosal lymphomas are curable when localised. MALT is associated with

Helicobacter pylori

infection. Eradication of the infection will usually induce remission (75%). Otherwise, chlorambucil or radiation treatment is used. Endoscopic follow-up is important. Splenic MALT lymphoma may follow hepatitis C infection; once other causes are excluded, splenectomy can induce a long remission.

4.

Mantle cell lymphoma (6%)

. The majority of these present as a systemic disease. Treatment is not very successful. The usual approach is combination chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy. Chemotherapy may be used with rituximab (the anti-CD20 antibody). Bone marrow transplant is offered to younger patients.

5.

Follicular lymphoma (22%)

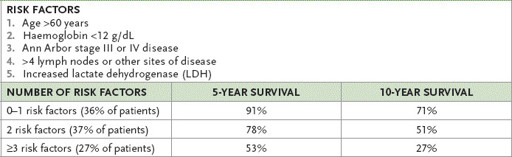

. Asymptomatic patients may require no treatment. Chlorambucil alone or combination treatment (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone – RCVP or rituximab cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone (RCVP) – RCHOP) can achieve a 75% remission rate. Interferon alpha seems to prolong survival once remission has been achieved, and rituximab upfront is standard now and can be helpful for patients who have relapsed. Between 5% and 7% of patients per year develop histological transformation into diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Follicular lymphoma (low-grade) prognosis can be further estimated from

Table 8.18

.

Table 8.18

Follicular lymphoma survival rates

6.

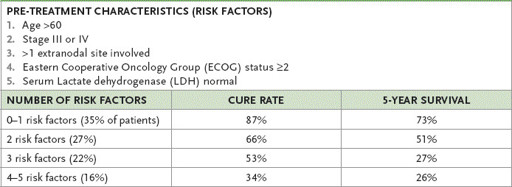

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (30%)

. Treatment is usually begun with combination chemotherapy (often CHOP). This may be followed by radiotherapy if there is bulky stage I or II disease. Six cycles of treatment will produce a cure in up to 70% of patients. Monoclonal antibody treatment with rituximab is used for most patients. Bone marrow transplant is more effective than further chemotherapy for patients who relapse: it can achieve up to 40% long-term disease-free survival. The International Prognostic Index (IPI), which is based on five pre-treatment characteristics (see

Table 8.19

), predicts survival.

Table 8.19

Cure rates and 5-year survival rates for diffuse large B cell lymphoma based on the International Prognostic Index (IPI)

7.

Burkitt’s lymphoma

. This is a rare disease in Australia, but is more common in Africa. Intensive combination chemotherapy with attention to the central nervous system will produce a cure in about 70% of patients.

8.

Hairy cell leukaemia

. This is an indolent lymphoma with leukaemic features. The peripheral smear shows lymphocytes with hairy projections. Look for splenomegaly and cytopenia. It responds well to chemotherapy with cladrabine.

9.

Immunodeficiency-associated lymphoma

. The WHO classifies these lymphomas into four groups:

a.

lymphoproliferative diseases associated with primary immune disorders

b.

HIV associated lymphomas

c.

post-transplant lymphomas

d.

methotrexate-associated lymphoproliferative disorders.

These are usually aggressive B cell, CNS and Hodgkin’s lymphomas, and treatment is as for the type of lymphoma.

BONE MARROW TRANSPLANT

Disease resistant to standard-dose chemotherapy can be treated with bone marrow ablation using chemotherapy or radiotherapy, or both. Bone marrow transplant is then performed with autologous stem cells or, less often, from a compatible donor. The mortality rate associated with this procedure (now <5%) and the success of engraftment have improved with the use of haematopoietic growth factors. Long-term outcomes are uncertain, as are the indications for the use of this treatment in patients with less aggressive disease. Follow-up of treated non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas is similar to that for Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients.

Multiple myeloma (myeloma)