Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (47 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Get the patient to walk to the end of the room, turn around and come back. Note – length of stride, smoothness of walk and turning around, stance, heel strike and arm swing. Is walking painful? Hemiplegic, Parkinsonian, foot drop and other neurological gaits should be obvious.

2.

Arms, legs and spine

a.

From behind

– look at the spine for scoliosis, muscle bulk of the shoulders, paraspinal muscles, gluteal muscles and calves; the iliac crests for loss of symmetry

b.

From the side

– look for normal lordosis and thoracic kyphosis. Ask the patient to bend; look for normal separation of lumbar spinous processes.

c.

From in front

– look for asymmetry or wasting of major muscle groups (shoulders, arms and quadriceps). Is there deformity of the knees, ankles of feet?

When arthritis seems likely to be an important part of the case, take the time to test movement. Look for restricted, asymmetrical or painful movements.

1.

Spine

– Rotation: ‘Turn your shoulders as far as you can to the right, and now to the left’. Lateral flexion: ‘Slide your hand down the side of the leg on the right side, and now on the left’. Cervical spine – lateral flexion: ‘Bend your right ear down towards your shoulder; now on the other side’. Flexion and extension: ‘Look up and back as far as you can. Now put your chin on your chest.’

2.

Shoulders (acromio-clavicular, gleno-humeral, sterno-clavicular joints)

– ‘Put your right hand on your back and reach up as far as you can as if to scratch your back; now the left.’ ‘Put your hands up behind your head and your elbows as far back as you can.’

3.

Elbows (extension)

– ‘With your elbows straight, put your arms down beside you.’

4.

Hands and wrists

– ‘Straighten out your arms and hands in front of you’. Look for fixed flexion deformity of the fingers and swelling and deformity of the hands and wrists or wasting of the small muscles of the hands. ‘Turn your hands up the other way.’ Look at the palms for swelling or muscle wasting. Is supination smooth and complete? Is there external rotation of the shoulder used to make up for limited supination? ‘Squeeze my fingers as hard as you can’ (tests for grip strength). ‘Touch the tip of each finger with your thumb’ (tests most finger joints).

5.

Legs and hips

– ‘Lie down on the bed for me’. Look at leg length and, if suspicious, measure true leg length from anterior superior iliac spine to medial malleolus and apparent length from umbilicus to medial malleolus. Test knee flexion: ‘Bend your knee and pull your foot up towards your bottom’. Meanwhile, put your hand on the patella and feel for crepitus. Test for osteoarthritis of the hip by internally rotating the hip. Flex the knee to 90° and move the foot laterally. Pain and limitation of movement occur early with osteoarthritis.

6.

Feet

– look for arthritic changes especially at the MTP joints, bunions, swelling, calluses, etc.

The examination will have to be varied for very immobile patients, but with practice it can be performed rapidly.

Rheumatoid arthritis

This is the most common of the inflammatory arthritides and is a very common long case in which the diagnosis is usually straightforward and the patient has many physical signs. The peak incidence of the onset of rheumatoid arthritis is in the fourth decade of life and it is three times as common in women as in men. There may be a family history and there is an association with human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR4 (70%). If left untreated, the disease leads to progressive and irreversible joint damage and deformity. Life expectancy is reduced by 10 years.

The history

1.

Ask when the diagnosis was made and whether diagnosis seems to have been delayed – the onset of rheumatoid arthritis in patients over the age of 60 is associated with a worse prognosis for those who are rheumatoid factor positive. Delay in diagnosis also leads to a worse outcome.

2.

Ask about the presenting features – most patients present with vague generalised symptoms, such as fatigue, anorexia and non-specific musculoskeletal pains; a

minority present with obvious oligoarticular arthritis; and a few present with severe constitutional symptoms and acute arthritis. Morning stiffness that lasts for more than an hour and continues for more than 6 weeks is characteristic of inflammatory arthritis but not of osteoarthritis.

3.

Ask about the initial treatment.

4.

Ask about the disease progression and which joints have been involved. The lumbar spine is never involved and the distal interphalangeal joints are only rarely affected.

5.

Enquire about the alterations in treatment over time and any complications encountered.

6.

Ask about the non-articular features of the disease:

a.

skin – Raynaud’s phenomenon, leg ulcers (

Fig 9.1

)

FIGURE 9.1

Leg ulcer in rheumatoid arthritis. T P Habif.

Clinical dermatology

, 5th edn. Fig 3.66. Mosby, Elsevier, 2009, with permission.

b.

eyes – dry eyes (and mouth; Sjögren’s syndrome), scleritis, episcleritis or scleromalacia perforans, cataracts (caused by steroids); iritis does not occur

c.

sore throat, hoarseness or neck pain – suspect cricoaryteroid joint disease; recurrent headaches at the base of the skull or arm tingling from C1–2 subluxation (obtain a lateral flexion cervical spine X-ray)

d.

lungs – dyspnoea owing to diffuse interstitial fibrosis or pleural effusion, pain as a result of pleuritis

e.

heart – chest pain owing to pericarditis, valve disease (from rheumatoid nodules), increased atherosclerosis

f.

renal – drug use, amyloid (all rare)

g.

nervous system – peripheral neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, cord compression (owing to cervical spine involvement (C1–2 subluxation) or rheumatoid nodules), entrapment neuropathy (particularly carpal tunnel syndrome)

h.

blood – anaemic symptoms owing to chronic disease, iron deficiency (from blood loss), folate deficiency (diet), Felty’s syndrome (rheumatoid arthritis with leucopenia and splenomegaly, and non-healing leg ulcers)

i.

systemic – fever, weight loss, fatigue

j.

vasculitic – digital arteritis, ulcers, mononeuritis multiplex, pyoderma gangrenosum.

7.

Ask about drug complications:

a.

aspirin (e.g. pain or nausea, gastric erosions or peptic ulcers causing bleeding, tinnitus)

b.

NSAIDs (e.g. ulceration, renal impairment, increased cardiac risk)

c.

methotrexate is often used and has a number of side-effects that need to be monitored (including hepatic and pulmonary toxicity, low white cell count and thrombocytopenia); the patient should know not to drink alcohol while taking methotrexate; an alternative drug (to methotrexate, not alcohol) is leflunomide (diarrhoea, alopecia, liver toxicity)

d.

penicillamine (e.g. nephrotic syndrome, thrombocytopenia, rashes, mouth ulcers, alteration in taste and, rarely, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), polymyositis, myasthenia gravis, Goodpasture’s syndrome or pulmonary infiltration)

e.

cyclosporin – monitor renal function and blood pressure

f.

hydroxychloroquine (e.g. nausea, pigmentation, bull’s eye retinopathy – need regular ophthalmological review)

g.

sulfasalazine (e.g. rash, nausea, haematological abnormalities, abnormal liver function tests, reversible oligospermia)

h.

anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) monoclonal antibody (e.g. increased risk of infections including reactivation of TB, positive ANA, lymphoma and demyelination)

i.

steroids.

8.

Ask about the major current problem – such as decreasing hand function, paraesthesiae, severe pain, etc.

9.

Find out about the current activity of the disease. This can be assessed historically by asking about the number of joints that have recently been involved with active synovitis, the severity and duration of early morning stiffness (very important), functional ability, changes in weight and the degree of systemic ill health. A severe course is more likely if there is the early appearance of rheumatoid nodules, an insidious onset and constitutional symptoms.

10.

Enquire about past medical history, especially regarding peptic ulceration, drug reactions or renal disease.

11.

Enquire about social background – ability to cope at home, ability to climb steps, independence in daily activities, ability to perform fine motor activities, the work environment, availability of support services. Smoking is a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis, particularly in developing anti-CCP (cyclic citrullinated peptide) positive rheumatoid arthritis.

12.

Ask about a family history (first-degree relatives) of rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, blood clots, diabetes (type 1), thyroid disease, miscarriages. Other types of auto-immune disease may be present in close relatives.

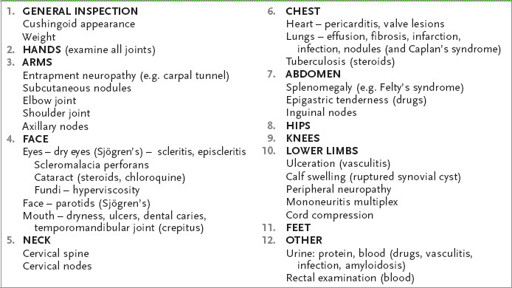

The examination (see

Table 9.1

)

A thorough general examination is important. In addition to assessing for synovitis in

every

joint, look particularly at the following:

Table 9.1

Rheumatoid arthritis

1.

general appearance – steroid complications, weight; remember that the pain arises mostly from the joint capsule and that acutely inflamed joints are held in the flexed position to increase the volume of the capsule and reduce pain

2.

the hands – including vasculitis and hand function; the wrist joints are almost always affected

3.

arms – the elbow and shoulder joints, rheumatoid nodules and axillary node enlargement

4.

the face – check the eyes for Sjögren’s syndrome, scleritis, episcleritis, scleromalacia perforans, cataracts, anaemia and signs of hyperviscosity in the fundi; enlarged parotid glands (Sjögren’s syndrome); the mouth (dryness, dental caries, ulcers); listen for a hoarse voice and palpate the temporomandibular joints (crepitus).

Note

: rheumatoid arthritis does not cause iritis

5.

the neck – for signs of cervical spine involvement

6.

the chest – the heart for pericarditis, conduction defects, aortic and mitral regurgitation; and the lungs for pleural effusion, fibrosis, nodules, infarction and Caplan’s syndrome

7.

the abdomen – for splenomegaly and epigastric tenderness

8.

the hips and knees

9.

the lower legs – for ulcers, calf swelling (ruptured Baker’s cyst), neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex and signs of cord compression

10.

the feet

11.

the peripheral nervous system for peripheral neuropathy or mononeuritis multiplex (caused by vasculitis)

12.

the skin, for cutaneous vasculitis (ischaemic ulcers on the legs or brown discoloured areas in the nail beds;

note

– exclude psoriasis)

13.

urine analysis for protein and blood; and rectal examination for blood (if there is a history suggestive of NSAID complications).

Differential diagnosis

Consider the differential diagnosis of a deforming symmetrical chronic polyarthropathy:

1.

rheumatoid arthritis

2.

psoriatic arthropathy and other seronegative spondyloarthropathies

3.

chronic tophaceous gout (rarely symmetrical)

4.

primary generalised osteoarthritis

5.

SLE (usually but not always non-deforming).

Remember that the causes of arthritis plus nodules include:

1.

rheumatoid arthritis (seropositive)

2.

SLE – rare

3.

rheumatic fever (Jaccoud’s arthritis) – very rare

4.

amyloid arthropathy (most usually in association with multiple myeloma).

Note

: Gouty tophi and xanthoma may sometimes be confused.