Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (35 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

7.

Multiple skin lesions (e.g. sebaceous adenomas and carcinomas, basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas, keratoacanthomas) occur in a variant of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (Torres syndrome).

Investigations

1.

Screening

. The possibility of hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC, or Lynch syndrome) should be considered for certain patients. This includes the ‘3–2–1’ rule (Amsterdam II Criteria): patients who have

three or more relatives

with a history of colon cancer where one of these is a first-degree relative of the other two; those who have colorectal cancer diagnosed in at least

two generations

of the family and those who have

one or more cases of colorectal cancer in family members

younger than 50. Screening starts at age 25 in affected families. In most kindreds with HNPCC, germ-line mutations have occurred in one of six DNA mismatch repair genes. Commercial testing is available for

hMSH2

and

hMLH1

mutations and these have a high sensitivity. ‘Microsatellite instability’ (MSI) is the expansion or contraction of short repeated DNA sequences. MSI has been observed in more than 90% of samples of tumour tissue from patients with HNPCC who fulfil the clinical (Amsterdam) criteria for this disease and also in up to 15% of tumours from patients with sporadic colorectal cancer. The presence of MSI may indicate a better prognosis and better response to adjuvant chemotherapy. Testing for the presence of MSI in a tumour or adenoma should be an initial screening test for patients suspected of having HNPCC, and positive cases should undergo genetic screening.

2.

Symptomatic patients

. Most will have had the cancer identified by colonoscopy. With the increasing introduction of screening measures in asymptomatic patients (e.g. faecal occult blood testing), earlier stage colon cancers will be detected in average-risk patients. The prognosis depends on the stage of disease. Survival is decreased if the bowel wall is penetrated (Dukes’ B2 stage) or with lymph node involvement (Dukes’ C stage).

Treatment

1.

For colon cancer, total tumour resection in local disease is the treatment of choice undertaken either endoscopically or surgically. Before surgery, patients should be evaluated for the possibility of metastatic disease, including a careful physical examination. Many physicians would also order a chest X-ray and liver function tests and measure the baseline carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level. If possible, a complete colonoscopy should be undertaken to look for evidence of synchronous cancers or polyps. If colonoscopy was not performed before the operation, it should be carried out as soon as practicable after the operation.

2.

Following a resection, patients are often followed up for 5 years with annual physical examinations and surveillance colonoscopy every 3 years. Measuring CEA levels every 3 months for 2 years after surgery for Dukes’ B or C stage disease, as a test for tumour recurrence, is often recommended but remains controversial.

3.

If metastatic disease is present, resection of the primary colorectal tumour does not change prognosis and should be done only for symptomatic reasons. The exception is limited metastases to the liver only, where 25% may be cured by resection.

4.

Determine whether the patient has had radiation therapy to the pelvis, which may have been offered with a rectal cancer. Some patients may have received chemotherapy; in particular, patients with Dukes’ C stage often have had adjuvant leucovorin modulated 5-fluorouracil for 6 months. Oxaliplatin may be added.

Chronic liver disease

Cirrhosis alone or in combination with other disease will often crop up, particularly in repatriation hospitals. (

Warning:

You may be exposed to prolonged war stories and discussions about shrapnel.) It is a pathological diagnosis. This discussion will be limited to aspects of cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, which tend to be most frequent in the examination.

The history

Cirrhosis can present with ascites (

Fig 7.9

), jaundice (

Fig 7.10

), abdominal pain, acute bleeding or encephalopathy. Occasionally patients present with only weakness, lassitude or loss of libido. There may be no symptoms (incidental cirrhosis).

FIGURE 7.9

Stretch marks. Ascites in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis showing distended abdomen; dilated superficial collateral veins; hemorrhagic scratch marks due to pruritus and coagulopathy; umbilical varices; plaster in left iliac fossa indicating diagnostic paracentesis. A Forbes, J J Misiewicz, C C Crompton, M Levine et al. (eds).

Atlas of clinical gastroenterology

, 3rd edn. 2005, in F Ferri.

Ferri’s clinical advisor 2012

. Fig 1-300, Mosby, Elsevier, 2012, with permission.

FIGURE 7.10

Jaundice.

Tropical dermatology

, 2006, Fig 12.15.

1.

Ask about length of history of liver disease:

a.

past history of hepatitis or jaundice, including contacts

b.

alcohol intake (in men, 80 g per day for more than 10 years is usually necessary; women need less exposure)

c.

history of drug addiction (intravenous), sexual orientation, transfusions, tattoos, etc.

d.

drug history (e.g. for chronic hepatitis: methyldopa, isoniazid, nitrofurantoin)

e.

history of diabetes mellitus, cardiac failure or arthropathy (haemochromatosis)

f.

overseas travel (e.g. acute hepatitis).

2.

Ask about treatment (e.g. protein restriction, fluid restriction, alcohol abstinence, steroids, lactulose, neomycin).

3.

Ask about complications, such as any history of encephalopathy. An early sign of this is reversal of the sleep cycle. Is there any history of portal hypertension (ascites or bleeding from varices), recent abdominal pain (gallstones – usually pigment stones, acute alcoholic hepatitis etc.).

4.

Ask about recent fever, abdominal pain or tenderness, or evidence of altered mental status – in the setting of ascites this suggests spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) and it is important to start antibiotic treatment as soon as ascitic fluid, blood, and urine have been obtained for culture and analysis. Determine if there have been one or more previous episodes of SBP, an indication for long-term prophylactic antibiotic therapy. In the setting of cirrhosis, an admission for GI bleeding is an indication for short-term antibiotic cover as mortality is reduced.

5.

Ask about investigations (e.g. liver biopsy, endoscopy for varices).

6.

Ask about operations (e.g. transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt – TIPS).

7.

Enquire about erectile dysfunction, loss of libido.

8.

Enquire about social problems (e.g. employment, family).

The examination

1.

Note the patient’s racial origin. Hepatitis B and C viruses are endemic in Southeast Asia, Italy and Egypt. Look for tattoos – tattoo needles are a source of infection. Examine carefully for the signs of chronic liver disease (

Figs 7.8

,

7.9

,

7.10

). Also note any hepatic encephalopathy, signs of portal hypertension, including splenomegaly, ascites, oedema and signs of bleeding (e.g. melaena).

FIGURE 7.8

Palmar erythema. A Nautiyal, K B Chopra. Liver palms – palmar erythema.

The American Journal of Medicine

, 2010. 123(7): 596–597 Fig 1.

2.

Consider hepatocellular carcinoma (particularly in haemochromatosis, and cirrhosis as a result of hepatitis B or C virus infection). In patients with decompensated cirrhosis, examine for a hard mass and liver bruit (hepatoma).

3.

Look for the signs of haemochromatosis. In young patients, consider Wilson’s disease and look carefully for Kayser-Fleischer rings (

Fig 7.11

). If there is deep jaundice with scratch marks and xanthelasma, particularly in a woman, consider end-stage primary biliary cirrhosis.

FIGURE 7.11

Kayser-Fleischer ring. M M Deguti, J F Uwe Tietge, E R Barbosa, E L R Cancado. The eye in Wilson’s disease: sunflower cataract associated with Kayser-Fleischer ring.

Journal of Hepatology

, 2002. 7(5).

4.

Exclude severe right heart failure, tricuspid regurgitation or constrictive pericarditis clinically in all patients. Search for other causes and sequelae (see

Tables 7.8

and

7.9

).

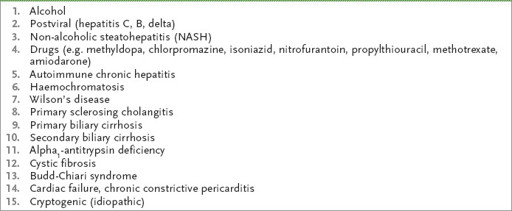

Table 7.8

Causes of cirrhosis in adults

Table 7.9

Sequelae of cirrhosis