Financial Markets Operations Management (30 page)

Read Financial Markets Operations Management Online

Authors: Keith Dickinson

Whilst the majority of purchase and sale transactions are settled on a DVP basis, there will be circumstances when DVP is not appropriate. These can include the following:

- Transfers of securities from one custodian to another on behalf of the same investor. In this case, as the investor has neither sold nor purchased the securities, there is no cash counter value.

- Purchases and sales for which the settlement of the securities occurs in a different location to that of the cash. An example could be where your purchased securities are delivered to your custodian, but payment is made separately to the seller.

In the first example, the delivering custodian will send an MT542 instruction (delivery free of payment â DFoP) to the clearing system and the receiving custodian will similarly send an MT540 instruction (receive free of payment â RFoP). A payment instruction is not required as there is no countervalue.

In the second example, your custodian will send an MT542 and you will make a separate payment to the seller.

For comparison purposes, the free of payment instruction types for SWIFT, EB and CBL are shown in

Table 8.9

.

TABLE 8.9

Selection of FoP message types

| RFoP | DFoP | Comments | |

| SWIFT message | MT540 | MT542 | |

| Euroclear Bank (EOC) | Â 01 F 03 F 03C F | Â 02 F 07 F 07C F | EOC's system: EUCLID EOCâEOC trade EOCâoutside EOC EOCâCBL bridge trade |

| Clearstream Banking Luxembourg (CBL) | Â 4F: RFP 6F: RF 4FCE:RF | Â 5F: DFP 8D/81: DF 5FCE: DF | CBL's system: Creation CBLâCBL trade CBLâoutside CBL CBLâEOC bridge trade |

We saw in Chapter 6 that the securities are held centrally within a Central Securities Depository (CSD). The CSD holds and maintains records of ownership including changes in ownership. It is therefore within the CSD that settlement takes place, based on clearing information passed down from the associated clearing system (clearing house or CCP).

Securities are expected to settle in full and straight away after the trade date. In reality, an amount of time is required for clearing and funding activities which results in a short time lag. On-exchange settlement conventions tend to be fixed, whilst off-exchange conventions can be more flexible (e.g. in Germany, on-exchange is T+2 and off-exchange can range from T+0 to T+40).

3

In general, the conventions are:

- Eurobonds â T+3 (changed on October 2014 to T+2)

- Equities â T+2

- Government â T+1

Logically, there is no reason why transactions should fail, especially in an era when securities are generally:

- Fungible;

- Deeply liquid;

- Held centrally within a CSD/ICSD environment;

- Easily and electronically transferable.

However, in the pre-settlement, clearing phase of a transaction, any unmatched transactions will not and cannot settle. In addition, taking the four bullet points in turn, there can be exceptions, such as:

- It is possible to hold bearer securities in non-fungible form. This can slow the delivery process as specific certificates need to be identified before delivery can occur.

- Many markets insist on minimum amounts of issued securities to be made available. This helps to reduce the risk of illiquidity on any one issue of securities. A problem arises when securities are sold to investors who either are unable or unwilling to make their positions available for securities lending purposes. This reduces the liquidity.

- Centrally-held securities have been a long-held objective for the market; however, it is possible in some markets for securities to be held outside the CSD/ICSD infrastructure (e.g. physical certificates held by investors themselves).

- We will discuss how securities are held in Chapter 10 and we will see that some securities still require re-registration of ownership either before settlement can occur or at some time shortly afterwards.

Whilst these exceptional situations will rarely prevent a transaction from failing outright, they can add delays and costs to the process.

Settlement fails are considered to be inevitable in many markets and almost impossible to eliminate totally. According to the European CSD Association

4

:

- In March 2012, the settlement efficiency rate in Europe was 98.9% in value terms and 97.4% in volume terms.

- Among the 1.1% of transactions (by value) that fail to settle on time, most will settle the following day, with a settlement fail rate of less than 0.5% on the intended SD+1.

The ECSDA also noted that three markets (Greece, Romania and Slovenia) demonstrated a 100% efficiency rate. Three factors explained this rate:

- The CSDs mostly settled on-exchange transactions that were pre-matched and directly input into the settlement system in full straight-through-processing mode.

- Buy-ins are automatically triggered if a trade fails to settle (on SD in Slovenia and SD+1 in Greece and Romania). In addition, in Slovenia, OTC trades either settle on SD or are cancelled before the end of SD.

- It was noted that Greece had 2.6% of the weighted average volume, Slovenia 0.09% and Romania 0.39%.

We will examine why transactions can fail to settle on the intended settlement date and what actions can be taken to resolve the problems.

Here is a list of possible reasons why transactions might fail:

- Processing problems â unmatched transactions;

- Sales â insufficient securities, inability to borrow or reverse repurchase;

- Purchases â insufficient cash, collateral or credit;

- Systemic issues.

We will consider these in turn.

Operations staff should ensure that any unmatched instructions are investigated and resolved at the earliest opportunity, and certainly before the settlement date. The institution that is found to be at fault can expect an interest claim from its counterparty, as shown in the example below.

Settlement fails can occur if there are insufficient securities with which to make a delivery. Let's look at some examples.

BD-A has the following positions with GSK 1.5000% bonds due in 2017 (GSK):

- A depot position of USD 3,000,000 GSK that is AFD;

- A purchase of USD 2,000,000 GSK against payment of USD 2,050,576.00 from BD-B, intended settlement date today (RVP); and

- A sale of USD 5,000,000 GSK against payment of USD 5,130,040.00 to BD-C, intended settlement date today (DVP).

- Situation:

We are informed that the purchase has failed and, as a result, the sale has also failed. - Problem:

Neither the sale proceeds nor the purchase costs have been credited/debited, leaving a net outstanding credit cash amount of USD 3,079,464.00. If the cash funding had been calculated on a fund-to-settle basis, this cash difference could have been allocated to another investment or been placed into the money market. Solution:

The reactive solution would be to wait until the purchase settles to provide sufficient bonds to settle the sale. In any case, Operations should chase the seller, who might be waiting to receive the bonds from one of its purchases. The proactive approach would be for BD-A to contact BD-C and offer a partial delivery of the USD 3,000,000 bonds already held in depot.BD-C is under no obligation to agree to this, but might do so if they require the bonds for another delivery and/or wish to maintain a good working relationship with BD-A.

- Actions required:

Assuming BD-C agrees to accept a partial delivery, the following actions should take place:- Both counterparties cancel the original instructions for USD 5,000,000 GSK.

- Both counterparties agree with the new amounts and then input instructions for new, re-shaped instructions:

- USD 3,000,000 GSK vs USD 3,078,024.00 cash, and

- USD 2,000,000 GSK vs USD 2,052,016.00 cash.

- USD 3,000,000 GSK vs USD 3,078,024.00 cash, and

- Both sets of re-shaped instructions will be matched.

- The USD 3,000,000 shape will settle, leaving the balance of USD 2,000,000 outstanding.

- There should be a full audit trail which tracks the re-shaping of the original USD 5,000,000 transaction into the two re-shapes (this helps the accounts and reconciliation functions to identify the new cash debit and credit amounts to be tracked).

- Both counterparties cancel the original instructions for USD 5,000,000 GSK.

It is quite possible for there to be more than one partial delivery, in which case the same re-shaping exercise must be completed. For example, BD-B might offer, say, USD 1,000,000 of the balance of USD 2,000,000 GSK to BD-A.

If BD-C does not agree to a partial delivery, BD-A might be able to borrow or “reverse repo” USD 2,000,000 GSK, for a fee, and fully settle the sale of USD 5,000,000 GSK bonds. We cover the topic of securities lending and borrowing and repo/reverse repo in Chapter 12: Securities Financing.

BD-A has the following positions with EDF 4.6000% Bonds due 2020 (EDF):

- A zero depot position of EDF;

- A purchase of USD 5,000,000 EDF against payment of USD 5,605,350.00 from BD-B, intended settlement date today (RVP); and

- A sale of USD 5,000,000 EDF against payment of USD 5,615,350.00 to BD-B, intended settlement date today (DVP).

- Situation:

We are informed that the purchase has failed and, as a result, the sale has also failed. - Problem:

Neither the sale proceeds nor the purchase costs have been credited/debited, leaving a net outstanding credit cash amount of USD 10,000.00. This situation is not as serious as in the example regarding partial settlement above. - Solution:

The reactive solution would be to wait until the purchase settles to provide sufficient bonds to settle the sale. In any case, Operations should chase the seller, who might be waiting to receive the bonds from one of its purchases. The proactive approach would be for BD-A and BD-B to agree to net out the bond positions and cash amounts. - Actions required:

The following actions should take place:- Both counterparties cancel the original instructions for USD 5,000,000 EDF.

- BD-B pays USD 10,000.00 cash to BD-A's bank account.

- There should be a full audit trail which tracks the changes to the bond and cash delivery/payment amounts.

- Both counterparties cancel the original instructions for USD 5,000,000 EDF.

Please note that this bilateral netting refers to the same pair of counterparties and the same security.

- Situation:

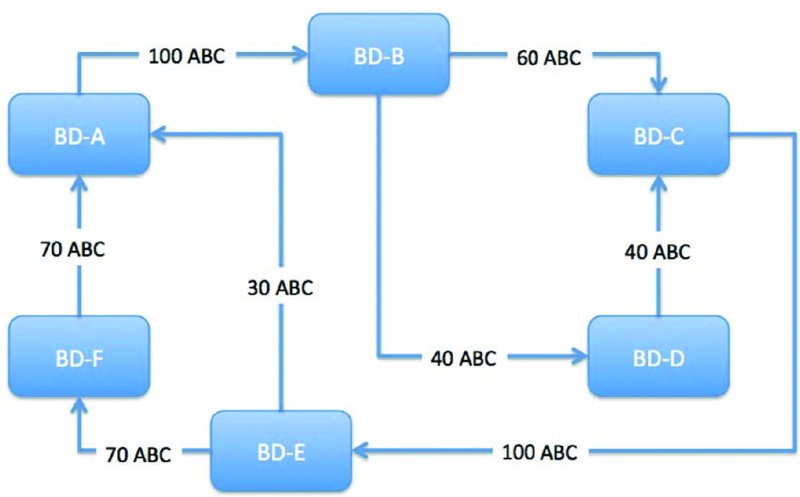

One particular security, for example ABC securities, has been traded amongst several broker/dealers, as noted in

Figure 8.2

. - Problem:

If we assume that not one of the counterparties has any ABC securities in depot, then all of the transactions in

Figure 8.2

will fail. When BD-C chases BD-B and BD-D, the responses will be the same, i.e. the counterparties are waiting to receive ABC from elsewhere. The same will happen when BD-B chases BD-A, and so on. Furthermore, the counterparties are only aware of the transaction they are involved with (so BD-E is only aware of its purchase of 100 ABC from BD-C and its sales of 70 ABC to BD-F and 30 ABC to BD-A). - Solution (A):

This situation presents a problem in a gross settlement environment unless all the counterparties can somehow ascertain each other's situations. One counterparty might attempt to borrow from another institution that is unconnected with this

gridlock. For example, if BD-A could borrow 100 ABC from an institutional investor or other broker/dealer, then the gridlock would unravel thus:- BD-A delivers 100 ABC to BD-B;

- BD-B now has 100 ABC and delivers 60 ABC to BD-C and 40 ABC to BD-D;

- BD-D now has 40 ABC and delivers 40 ABC to BD-C;

- BD-C now has 100 ABC and delivers 100 ABC to BD-E;

- BD-E now has 100 ABC and delivers 70 ABC to BD-F and 30 ABC to BD-A;

- BD-F now has 70 ABC and delivers 70 ABC to BD-A;

- BD-A now has 100 ABC and returns 100 to the institutional investor or other broker/dealer.

- BD-A delivers 100 ABC to BD-B;

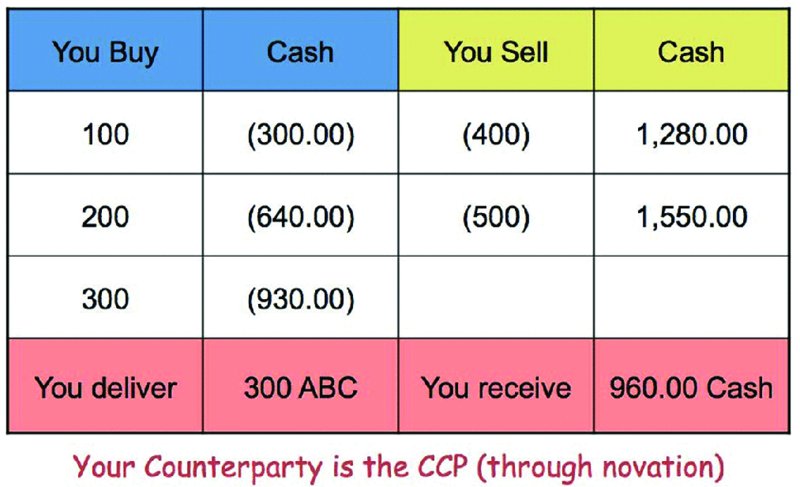

- Solution (B):

In a multilateral netting system where the clearing system novates the transactions, the system has oversight of each and every participant's depot balance, credit situation and outstanding transactions. If the situation was appropriate, the clearing system would mark each transaction as settled, passing debits and credits to the securities and cash accounts for each participant. See

Figure 8.3

for a simplified solution.

FIGURE 8.2

Gridlock with ABC securities transactions

FIGURE 8.3

Multilateral netting

We have concentrated on the seller's lack of securities as being the prime cause of settlement fails. Even if the seller does have availability, if the buyer has insufficient cash or access to credit or financing, the settlement could still fail. Problems with cash are generally due to funding mistakes and are resolved quickly.

The purchaser's cash-related problems will result in interest claims from the seller, with the interest rate charged being close to the typical overdraft rate for the currency at the time of the claim.

We have seen that settlements might fail for a variety of reasons, either due to the lack of availability of an asset or an operational error. Fails are usually corrected within a day or so.

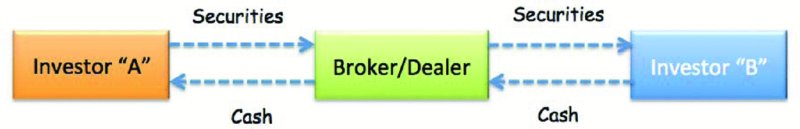

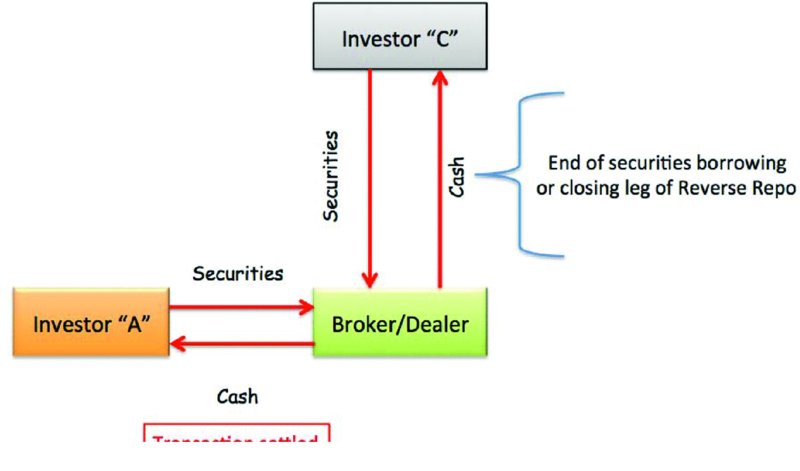

Failed sales or deliveries can be managed by borrowing securities or using “reverse repo”; we cover the topic of securities financing in Chapter 12. In the sequence shown in

Figures 8.4

,

8.5

and

8.6

, we see how a failed or failing transaction can be completed.

FIGURE 8.4

Fails management (a)

FIGURE 8.5

Fails management (b)

FIGURE 8.6

Fails management (c)

Suppose investor A sells bonds to a broker/dealer, who then resells the bonds to investor B. The delivery and payment obligations of the three parties on the morning of the settlement date are shown with dotted lines in

Figure 8.4

.

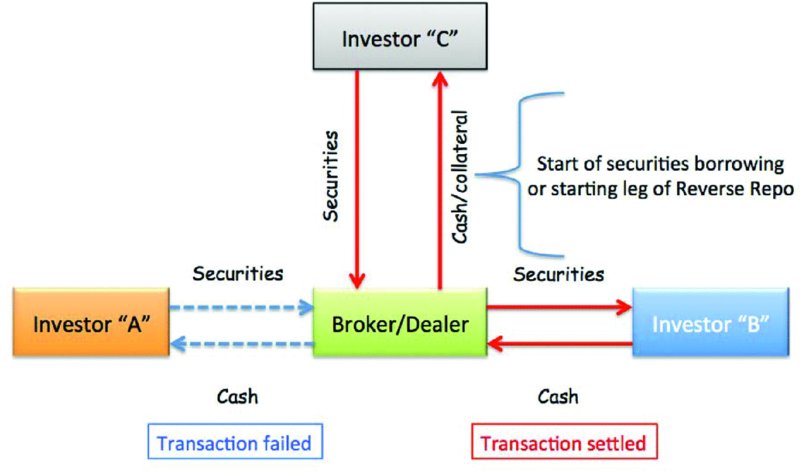

If A fails to deliver the securities to the broker/dealer, this will cause the broker/dealer to fail B. To cure its fail to B, the broker/dealer can either borrow or “reverse repo” the securities from investor C and deliver the borrowed/reversed securities. Actual settlement of securities and cash are shown with solid lines in

Figure 8.5

. The original failed transaction between A and the broker/dealer is shown with dotted lines.

Investor A finally delivers the securities to the broker/dealer who can now terminate the securities borrowing/reverse repurchase agreement with investor C (

Figure 8.6

).

We have seen that settlement fails can be resolved without too much trouble; they are not deliberate and usually occur because the seller does not have the securities available for delivery. Alternatively, the purchaser may not have sufficient cash or available credit. There are means by which counterparties can work around fails (e.g. through partial settlement or by using bilateral letting).

From time to time, however, it may not be possible to resolve settlement fails other than by enforcing a chain of events that will enable the transactions to settle not with the original counterparty but through a third party. These events are known as

buy-ins

and

sell-outs

and can either be invoked at the discretion of the affected counterparty or compulsorily by the relevant stock exchange.

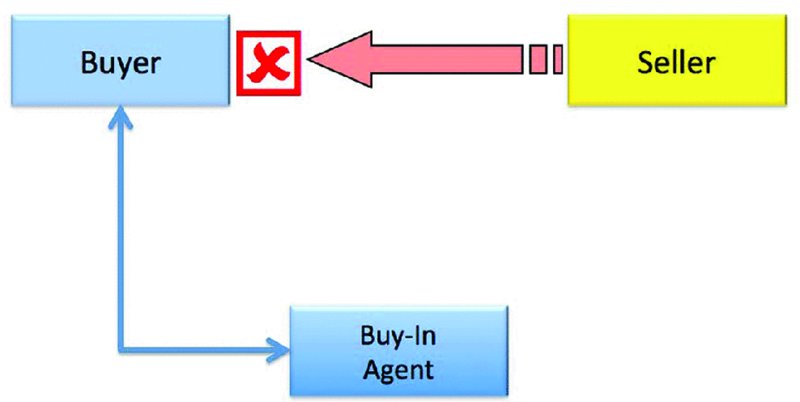

A buy-in occurs when a seller is unable to deliver securities (see

Figure 8.7

). The buyer needs to find a market participant who not only has the required inventory but is also willing to sell the securities to the buyer. This market participant can be, for example, another dealer that ordinarily would be a competitor to the buyer, but in this instance is willing to act as a buy-in agent.

FIGURE 8.7

Buy-in

The buyer will be expected to warn the seller of its intention to buy the securities in and, after a predetermined amount of time, will execute the buy-in. If the reason for the settlement failure was that the seller was also awaiting securities from a previous purchase, then it might appear that the seller also has to arrange for a separate buy-in.

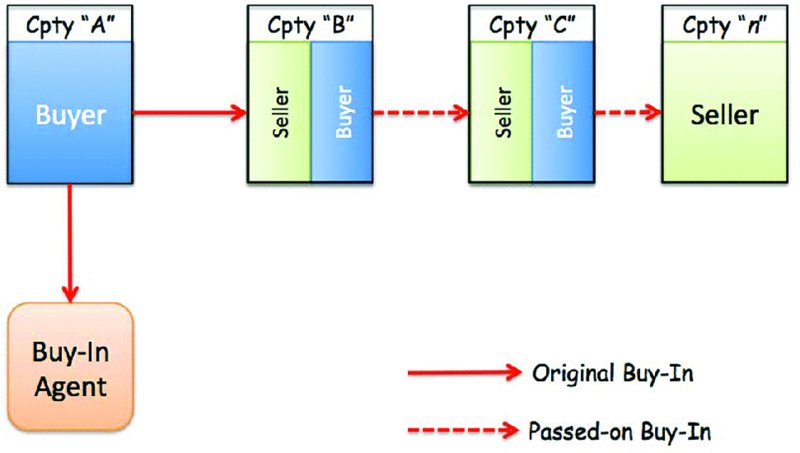

Indeed, there could be a longer chain of failed transactions, and to overcome the requirement for multiple buy-ins, the original buy-in is “passed on” from the first seller's counterparty along the chain to the counterparty that effectively caused the problem.

In

Figure 8.8

you can see that counterparty “A” (the original buyer) has bought in securities against counterparty “B” using an appropriate buy-in agent. For its part, counterparty “B” has passed the buy-in notice on to its counterparty “C”, who, in turn, has passed it on to the final failing seller, counterparty “

n

”.

FIGURE 8.8

Buy-in pass on

Let us consider two examples of a buy-in; in the first of these we will see how the Eurobond market handles a buy-in and in the second, we'll see how a buy-in is automatically initiated in the Singapore market.

For member firms of the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), the decision to apply a buy-in rests with the buyer (and with the seller for a sell-out). If the buyer is in no particular rush to receive the securities, it might take the decision to wait until the seller is able to deliver. Under ICMA's rules, Section 450: Buy-In,

5

member firms have the right to issue the seller with a buy-in notice. The notice warns the seller that if it fails to deliver the securities within five business days, the buy-in will be executed. The buy-in agent must be an ICMA reporting dealer but must not be affiliated with the buyer.

In the event that the original transaction fails to settle, the buy-in is executed at the best market price for guaranteed delivery on the normal settlement date convention (i.e. T+3). The original buyer is entitled to claim the difference between the original purchase price and the bought-in price from the original seller (as shown in

Table 8.11

).

TABLE 8.11

Buy-in price difference

| Price | Counterparty | |

| Original purchase | 101.6875 | Seller |

| Bought-in price | 101.8125 | Buy-in agent |

| Difference | 0.1250 | Charged to the seller |

In Singapore, we have an example of a buy-in process that is automatically initiated by the local clearing system. For transactions executed on the Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX), the local clearing system (central depository)

6

will automatically execute a buy-in if the seller has insufficient securities available for delivery by noon on the intended settlement date (T+3).

The buy-in price starts at the higher of two minimum bids above the previous day's closing price or any of the transacted/bid prices available one hour before the buy-in commences. In addition, the CDP charges a processing fee and brokerage on each buy-in contract.

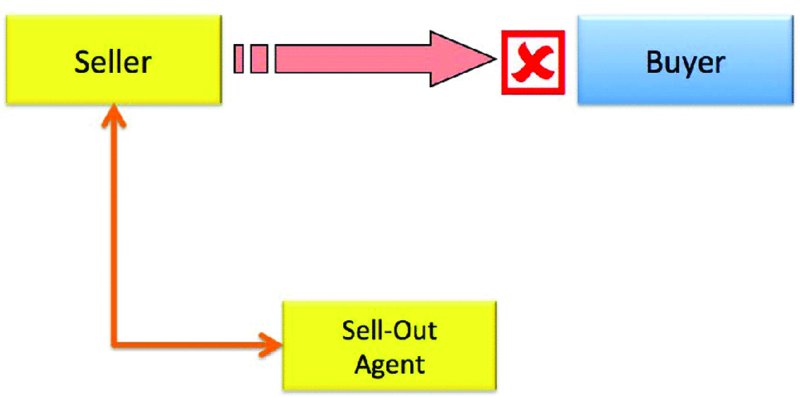

But what if the buyer is unable to arrange suitable financing? In this case, there might be a strong possibility that the buyer is close to defaulting. Were this to be the case, the transaction would remain unsettled and the seller would not receive the cash proceeds from its sale. The ICMA rules make provision for this situation in Section 480: Sell-out. Section 480 is essentially a mirror of Section 450 except that partial deliveries are not acceptable and there is no provision for a pass-on (see

Figure 8.9

).

FIGURE 8.9

Sell-out