Financial Markets Operations Management (29 page)

Read Financial Markets Operations Management Online

Authors: Keith Dickinson

Clearing is a set of post-trade activities and is the process of transmitting, reconciling and, in some cases, confirming payment orders or security transfer instructions prior to settlement, possibly including the netting of instructions and the establishment of final positions for settlement.

As soon as the trade is captured from the Front Office systems, it goes through the following stages:

- Trade validation and enrichment â this takes the basic trade details and adds extra information such as the settlement date, cash amounts, accrued interest, fees and commissions, etc.;

- Trade confirmation â exchanging confirmations between market participants or affirming trade details with customers/clients;

- Transmitting delivery/receipt instructions to a clearing system;

- Responding to unmatched reports from the clearing systems;

- Forecasting cash requirements and securities availability.

On the satisfactory completion of the clearing process, the transactions can go forward to settlement. This is the topic of the next chapter.

Settlement and Fails Management

In the previous chapter we followed a typical transaction from the Front Office through to clearing. In this chapter we will cover the final phase in the transaction lifecycle, in which the liabilities of both the buyer and the seller are completed. We refer to this as

settlement

.

The term “settlement” can be defined as:

This

1

definition is valid for securities and other cash market financial instruments, but what about derivatives? “Open” derivatives contracts can be open for months, if not years, and the concept of settlement is only truly valid when derivatives contracts are exercised, i.e. in instances where the underlying asset is delivered or received. You will recall from the previous chapter that open derivatives contracts are either margined (for open exchange-traded and cleared OTC derivatives transactions) or collateralised (for non-cleared OTC derivatives).

In this chapter you will learn about the following topics:

- The different types of settlement;

- The concept of delivery versus payment and the three BIS DVP models;

- The locations in which settlement takes place;

- The reasons why transactions fail to settle;

- The ways in which settlement fails are managed.

In the BIS/CPSS definition of settlement above, you will have noticed the term “DVP”. We will discuss this in Section 8.3.

Whilst it would appear from the definition that the seller delivers securities direct to the buyer (and the buyer pays the seller), in reality most settlements take place by a process known as

book-entry transfer

; in other words, electronic transfers rather than physical transfers.

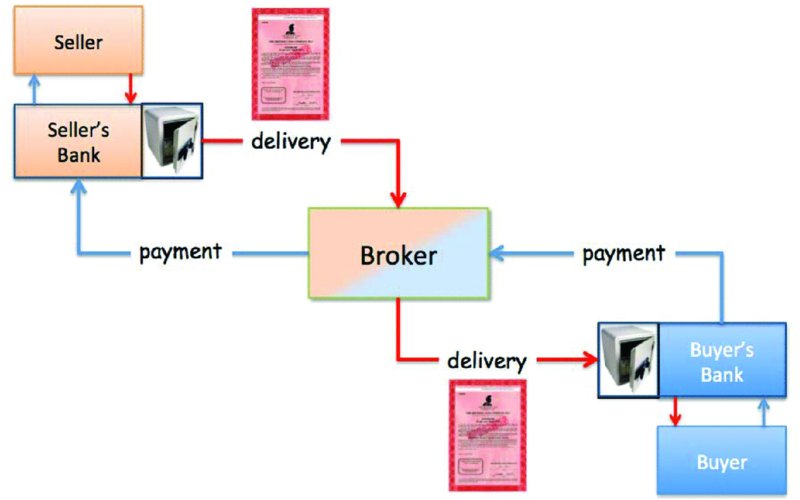

In the days when securities were certificated (i.e. held in physical form) investors would typically arrange for their banks to hold their share and bond certificates in the banks' own vaults. In order to settle their sales, the investors would instruct their banks to withdraw the appropriate certificates from the vaults. Having done this, the banks would arrange for the buyers' brokers to collect the certificates, together with any transfer documentation, and in exchange hand a cheque or bank draft to the bank by way of payment.

This activity required a small army of bank and broker messengers who would spend their day delivering payments in exchange for securities and delivering securities in exchange for payment. We could describe this as an extreme example of a decentralised settlement system (see

Figure 8.1

). Today, not only is the clearing process centralised but also the settlement process. This makes settlement much more efficient and cost-effective and enables the settlement cycle to be shortened from trade date plus many days to trade date plus three days or less.

FIGURE 8.1

Physical settlement

One further consequence is that we do not see many messengers.

Today, in the 21st century, securities are delivered electronically by book-entry transfer. Delivery can be made either on a transaction-by-transaction basis or on a collective basis. The former is known as

gross settlement

and the latter as

net settlement

.

Consider the example shown in

Table 8.1

, in which an investor has an inventory position of 1,000,000 ABC shares, all of which are available for delivery, and has executed a number of transactions (see

Table 8.1

). (We can ignore the cash counter values for the purposes of this example.)

TABLE 8.1

Gross settlement â total 1 million shares

| Direction | Quantity of Shares | Counterparty |

| Sale | (150,000) | Broker “A” |

| Sale | (500,000) | Broker “B” |

| Sale | (350,000) | Broker “C” |

| Total: | (1,000,000) |

In terms of timing, the settlement system can settle these trades in one of two ways:

Settlement in real time:

As soon as the securities are available, the transaction(s) will be settled. This is a continuous process with no waiting involved. We refer to this version as

real time gross settlement

(RTGS).In our example above, all three transactions would settle as soon as the settlement system opened for business (at, say, 08:30).

Settlement at a designated time:

The settlement system will defer the actual settlement to a predetermined time during the settlement day, for example, at the close of business. Although the securities are available, there is an intra-day delay until the actual settlement happens. We refer to this version as a single

batch

process.There is no reason why a settlement system could not operate a multi-batch process with settlement taking place at, say, 10:30, 13:00, 15:00 and 17:00 (local time). The multi-batch process now begins to resemble RTGS.

In our example above, all three transactions would settle at 10:30 (two hours later).

If we add two more transactions to our example and add the settlement times (see

Table 8.2

), you can see that all the transactions have settled on the same day albeit at different times. Even if Broker D's 200,000 shares were available from 13:01, settlement would only have been completed in the next batch at 15:00.

TABLE 8.2

Gross settlement â timing issues

| Direction | Quantity of Shares | Counterparty | Settlement Time |

| Sale | (150,000) | Broker “A” | 10:30 |

| Sale | (500,000) | Broker “B” | 10:30 |

| Sale | (350,000) | Broker “C” | 10:30 |

| Purchase | 200,000Â | Broker “D” | 15:00 |

| Sale | (200,000) | Broker “E” | 15:00 |

| Total: | (1,000,000) |

By contrast, a net settlement system would be able to reduce overall exposures by offsetting deliveries and receipts, leaving a smaller net obligation. In net settlement, all the inter-institution transactions in the same security and all due for settlement on one particular day are accumulated. At the end of the day, the settlement accounts of the institutions are adjusted to reflect either one debit/delivery or one credit/receipt in that security, as shown in the example in

Table 8.3

.

TABLE 8.3

Net settlement

| Direction | Shares | Counterparty | Net Position | Delivery |

| Sale | (150,000) | Broker “A” | ||

| Sale | (500,000) | Broker “A” | (650,000) | To Broker “A” |

| Sale | (350,000) | Broker “B” | ||

| Purchase | 200,000Â | Broker “B” | ||

| Sale | (200,000) | Broker “B” | (350,000) | To Broker “B” |

| Total: | (1,000,000) | (1,000,000) |

In this example, there will be two deliveries rather than the five that would have happened in the previous gross settlement example.

For the six transactions, there were only three actual credits/debits plus two zero movements, with an overall net movement of zero. In other words:

- The net debits and credits total zero, and

- The closing position total is the same as the opening position total.

The question above requires the central counterparty/clearing house to monitor the incoming settlement instructions so that it can perform the settlement netting exercise. This could not be done by the participants themselves as, for example, counterparty “A” is only aware of its three transactions (Refs 1 to 3) and cannot know what transactions the other counterparties have executed amongst themselves (Refs 4 to 6).

The common theme in all four scenarios is the separation of the securities transfer and the corresponding payment of cash. In order to overcome the separation, it is good market practice to ensure that delivery and payment occur at the same time and in the same place. Furthermore, if the seller does not have availability for delivery and/or the buyer does not have sufficient cash, then the transaction will not settle.

From the seller's point of view, we refer to this connection of securities and cash as

delivery versus payment

or DVP. Conversely, from the buyer's point of view, we have

receipt versus payment

or RVP. Irrespective of whether we are discussing a sale or a purchase, we tend to use the term DVP in both instances.

In 1989, the Group of Thirty (G30) published a document entitled

Clearance and Settlement Systems in the World's Securities Markets

which addressed the issues and challenges of clearing

and settlement. From the workings of the G30's Steering Committee, nine recommendations were made.

Recommendation 5 stated that: “Delivery versus payment should be employed as the method for settling all securities transactions.” Commenting on this recommendation, the G30 noted that:

“An area of substantial risk in the settlement of securities transactions occurs when securities are delivered without the simultaneous receipt of value by the delivering party. Simultaneous exchange of value is important to eliminate the risk of ⦠failure to perform according to contract. DVP effectively eliminates any exposure due to delivery delay by a counterparty.”

2

The G30 subsequently defined DVP as the:

On this basis, not one of the four scenarios noted above would be regarded as settlement on a DVP basis.

In summary, a DVP system is a securities settlement system that provides a mechanism to ensure that delivery occurs if (and only if) payment occurs. Furthermore, the mechanism ensures that payment occurs if (and only if) delivery occurs.

Three broad structural approaches (shown in

Table 8.7

) to achieving DVP were identified by the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems (CPSS) and these approaches are referred to as

models

.

TABLE 8.7

DVP models

| Model | Definition |

| 1 | Systems that settle transfer instructions for both securities and funds on a trade-by-trade (gross) basis, with final (unconditional) transfer of securities from the seller to the buyer (delivery) occurring at the same time as final transfer of funds from the buyer to the seller (payment). |

| Summary: | Gross, simultaneous settlements of securities and funds transfers. |

| Example: | See the example that we used earlier for gross settlement. |

| 2 | Systems that settle securities transfer instructions on a gross basis, with final transfer of securities from the seller to the buyer (delivery) occurring throughout the processing cycle, but that settle funds transfer instructions on a net basis, with final transfer of funds from the buyer to the seller (payment) occurring at the end of the processing cycle. |

| Summary: | Gross settlement of securities transfers followed by net settlement of funds transfers. |

| Example: | Consider the following three transactions:

Settlement using Model 2 would be:

|

| 3 | Systems that settle transfer instructions for both securities and funds on a net basis, with final transfers of both securities and funds occurring at the end of the processing cycle. |

| Summary: | Simultaneous net settlement of securities and funds transfers. |

| Example: | Consider the following three transactions:

Settlement using Model 3 would be:

|

Refer to Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems (online). “Delivery versus payment in securities settlement systems”. Available from

www.bis.org/publ/cpss06.htm

. [Accessed Tuesday, 11 March 2014]

Institutions that are participants of the SWIFT messaging system will use the standardised RVP/DVP message types. In addition, clearing systems will offer their own proprietary communication system. For example, both ICSDs, Euroclear (EOC) and Clearstream Banking Luxembourg (CBL) use their proprietary systems and SWIFT, as shown in

Table 8.8

.

TABLE 8.8

Selection of DVP/RVP message types

| RVP | DVP | Comments | |

| SWIFT message | MT541 | MT543 | |

| Euroclear Bank (EOC) | Â 01 P 03 P 03C P | Â 02 P 07 P 07C P | EOC's system: EUCLID EOC-EOC trade EOC-domestic trade outside EOC EOC-CBL bridge trade |

| Clearstream Banking Luxembourg (CBL) | Â 41: RVP 61: RVP 41CE: RVP | Â 51: DVP 8M/8A: DVP 51CE: DVP | CBL's system: Creation CBL-CBL trade CBL-domestic trade outside CBL CBL-EOC bridge trade |