Financial Markets Operations Management (31 page)

Read Financial Markets Operations Management Online

Authors: Keith Dickinson

The majority of transactions that fail on the intended settlement date will eventually settle within a day or two, whether it takes the trading counterparties to intervene (e.g. arrange a partial settlement) or the clearing system to automatically initiate a buy-in.

Situations can arise, however, which have led to chronic fails, as the following two examples demonstrate (one involved government securities and the other foreign exchange).

We saw that settlement efficiency is mostly very high, especially in Europe according to the ECSDA research noted above. This, together with the removal of physical certificates and the settlement of most asset classes by book-entry transfer, begs the question as to why we need several days to process transactions when, in theory, it should be possible to settle any transaction on the trade date. This “trade date settlement” idea has one big advantage: counterparty risk exposure is reduced from several days (e.g. T+3) to intra-day and consequently the need for margin/collateral to be posted for the duration of the open trade status is reduced. Systemic risk is also reduced, with fewer open trades waiting for SD in a pending queue.

There are some challenges, however:

- The institutional client part of the industry may not be willing or able to replace legacy systems with state-of-the art, fully automated STP systems that can cope with shorter processing cycles.

- As we will see in Chapter 10: Custody and the Custodians, there are long, time-consuming communication chains from the client to the foreign CSD.

Although not announced as such, the “compromise” option is to reduce the settlement cycle across the globe to T+2. This provides sufficient time for processing (with the timing and communication issues noted above) and reduces the counterparty risk exposure to a more acceptable level.

The European Commission announced its intention to introduce T+2 settlement in all 27 Member States with effect from 1 January 2015. Germany already operates under T+2, with other markets typically under T+3. Government securities tend to be under T+0 or T+1.

Like Europe, the settlement is fragmented. Unlike Europe, there is no regulatory driver for harmonisation; nevertheless, there is a reasonable degree of harmonisation with markets such as India, Hong Kong, Korea and Taiwan already operating under T+2 and other markets such as Australia, China, Singapore and Japan under T+3. As other regions and markets migrate to T+2, it is probable that T+3 markets will follow.

In 1995, the USA shortened its settlement cycle from T+5 to T+3, with plans for a further move to T+1 shelved in the early 2000s. In April 2014, the DTCC announced that it would support a move to T+2 with a three-year implementation timescale.

Currently on a T+3 cycle, Canada has no immediate plans other than to observe what the USA does.

The international bond business is OTC and, as such, does not directly come under the European Commission's requirements to move to T+2. One of the key provisions of the new regulations is the requirement: “⦠that the intended settlement date for transactions in transferable securities which are executed on regulated markets, MTFs or OTFs shall be (T+2). But this does not apply to transactions which are negotiated privately but executed on trading venues, nor to transactions which are executed bilaterally but reported to a trading venue.”

7

To overcome the potential dual settlement date convention, ICMA's John Serocold stated that: “The emerging conclusion is that ICMA's Secondary Market Rules and Recommendations should be amended to provide for T+2 settlement in the absence of agreement to the contrary.”

8

This moved occurred on 6 October 2014.

In this chapter we have seen that settlement is the completion of any transaction. There are two types of settlement:

- Gross settlement, where individual transactions settle on a one-by-one basis. Whilst this means that transactions settle in the shape and size that they were executed, it does allow settlement to occur in real time.

- Net settlement, where a clearing system will net out deliveries and receipts, debits and credits across its clearing members' securities and cash accounts. In order for this to happen, the clearing system has to accumulate the deliveries and receipts over a period of time before netting can take place. This netting might only occur once in a day or several times throughout the day. The more frequently netting can occur, the more similar it becomes to real-time settlement.

One of the operational risks that can occur is

settlement risk

, where one half of the transaction settles (e.g. securities are delivered) and the other half of the transaction fails (e.g. payment is not made). To mitigate this risk, it is normal market practice for settlement to take place on a delivery versus payment (DVP) basis.

There are three so-called DVP models, as defined by the Bank for International Settlements' Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems:

- Model 1: Gross, simultaneous settlements of securities and funds transfers.

- Model 2: Gross settlement of securities transfers followed by net settlement of funds transfers.

- Model 3: Simultaneous net settlement of securities and funds transfers.

Although DVP is the preferred method of settlement, there are occasions when this may not be appropriate (e.g. an investor is transferring his assets from one custodian to another without there being any change of beneficial owner). In this situation, the transfer will be made without any counter value, i.e. on a free-of-payment basis. FoP deliveries require greater operational oversight than DVP, because if the free deliveries are made to the wrong recipient, there is the risk that the deliverer may not get the assets back.

With securities it is expected that settlement is made in full shortly after the trade is executed. As a certain amount of time is required for the clearance and funding processing to take place, it is appropriate that the intended settlement date should be between one and three days after the trade date. In general terms, government securities tend to settle on T+1, Eurobonds on T+3 and equities around the T+2 to T+3 timespan.

Most transactions do settle on the intended settlement date, although for liquidity-related reasons some do fail to settle on time. Participants can either wait or make arrangements to manage the settlement fails through one or more of the following techniques:

- Partial settlement;

- Bilateral netting;

- Multilateral netting through a securities settlement system;

- Invoking buy-ins or sell-outs, as appropriate.

Fails can occur on rare occasions through systemic problems and these can require intervention from a central authority (e.g. a government issuing a new tranche of securities) or the introduction of a new centralised system (e.g. the foundation of CLS Bank in the foreign exchange industry).

Finally, the move to universal T+2 settlement is gaining momentum, especially in Europe, with the USA and Canada some way behind and the rest of the world somewhere in between.

Derivatives Clearing and Settlement

We described some of the derivative products in Chapter 2: Financial Instruments and noted that these products can be subdivided into two types:

- Exchange-traded derivatives (ETDs)

- Over-the-counter derivatives (OTCDs).

This distinction guides us in terms of the post-transaction processing. Until recently, ETD transactions were cleared through a central counterparty (CCP) and OTCD transactions were processed between the trading counterparties. Today, it is expected that OTCD transactions are also cleared centrally; a change that has come about through regulatory pressure.

Central counterparties (CCPs) support trade and position management across a wide range of asset types including securities and derivatives. The concepts for derivatives clearing are similar to those for securities; however, there are some significant differences, including:

- After securities transactions have been cleared, settlement occurs in the appropriate central securities depository. There is no such concept of a CSD for derivatives. Cleared derivatives positions are managed by the CCP and non-cleared positions by the two counterparties involved.

- Securities are settled in full shortly after trade execution. This means that the counterparty risk between buyer and seller (in a clearing house context) is extinguished on settlement and, likewise, between buyer and CCP together with seller and CCP.

- Derivatives contracts remain open until they are either closed out or are exercised. This results in a credit exposure for the duration of the open status of the contract. This risk is mitigated in part by the use of margin (cleared derivatives) and collateral (non-cleared).

The purpose of this chapter is to show you the ways in which ETDs and OTCDs are cleared. By the end of this chapter you will:

- Understand how cleared and non-cleared derivatives are processed;

- Be able to calculate margin calls for cleared derivatives;

- Be able to calculate collateral requirements for non-cleared derivatives;

- Understand why the regulators introduced changes to the post-trade processing of OTCDs.

For some time before the 2007/2008 financial crisis, large volumes of bilateral OTC derivatives transactions: “ ⦠had created a complex and deeply interdependent network of exposures that ultimately contributed to a build-up of systemic risk. The stresses of the (2007/2008 financial) crisis exposed these risks: insufficient transparency regarding counterparty exposures; inadequate collateralisation practices; cumbersome operational processes; uncoordinated default management; and market misconduct concerns.”

1

In September 2009, the G20 heads of state, together with other invited heads of state and international organisations, held the third ``Summit on Financial Markets and the World Economy'' in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

From this Summit, the G20 agreed to reform the OTC derivatives markets with the objectives of improving transparency, mitigating systemic risk and protecting against market abuse. The key elements in achieving this reform were that:

- All standardised OTC derivatives should be traded on exchanges or electronic platforms, where appropriate.

- All standardised contracts should be cleared through central counterparties (CCPs).

- OTC derivatives contracts should be reported to trade repositories.

- Non-centrally cleared contracts should be subject to higher capital requirements.

2

Margin requirements were added to the reform programme by the G20 in 2011.

We will address these four elements in Section 9.4 on cleared derivatives.

The FSB has assumed responsibility for the oversight of this project and collates information from its member countries regarding progress made.

The FSB publishes regular progress reports on its website (

www.financialstability-board.org

). In its summary of the 7th Progress Report, dated 8 April 2014, the FSB noted that:

- There has been continued progress in the implementation of OTC derivatives market reforms.

- Market participants' use of centralised infrastructure continues to increase.

- Overall, there are clear signs of progress in the implementation of trade reporting, capital requirements and central clearing.

- Implementation of reforms to promote trading on exchanges or electronic trading platforms, however, is taking longer.

3

There are five areas that require market reforms. These are:

- Trade reporting;

- Central clearing;

- Capital requirements;

- Margin requirements;

- Exchange and electronic platform trading.

In order to meet these reform objectives a number of practical issues have emerged, including the concern that: “ ⦠regulatory requirements are implemented in a consistent and coordinated fashion across jurisdictions, given the highly cross-border nature of OTC derivatives markets”.

4

As you will have observed in the FSB's summary (see above), progress has been taking place across all five areas. As at the end of March 2014, progress could be summarised as follows:

- Trade reporting:

The majority of FSB member jurisdictions have trade reporting requirements either partially or fully in effect. Full implementation for all jurisdictions is expected by the end of 2014. - Central clearing:

China, Japan and the USA have implemented clearing mandates. Other jurisdictions have adopted regulation (Korea and India), proposed regulation (Mexico and Russia), published assessments (Australia), commenced authorising CCPs (EU) or adopted legislative framework for further reforms (Hong Kong). - Capital requirements:

Capital requirements are now effective in more than half the member jurisdictions, with only Indonesia yet to make any preliminary studies (although this is anticipated during 2014). Almost all other jurisdictions should have requirements in effect by the end of 2014.

5 - Margin requirements:

The framework for non-centrally cleared derivatives was finalised by the BCBS-IOSCO

6

in September 2013, but only the EU and the US have taken any regulatory steps towards implementation. Several jurisdictions anticipate taking steps toward implementation closer to 2015. - Exchange and electronic platform trading:

China, Indonesia and the US now have regulations requiring organised platform trading, with other jurisdictions having the legislative frameworks in place.

Unlike securities transactions where settlement occurs shortly after the trade date, derivatives transactions can remain open for much longer periods of time, ranging from a few months to many years. This time delay exposes participants to credit risk and this can include “counterparty-to-counterparty” and “clearing system-to-counterparty” exposures.

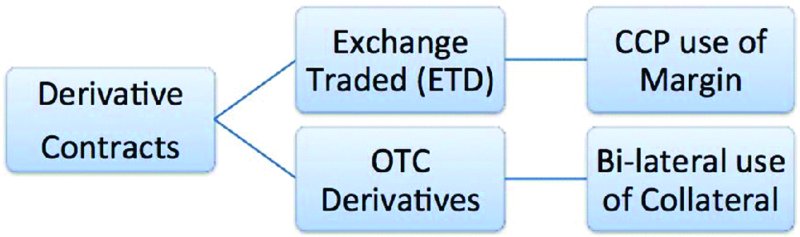

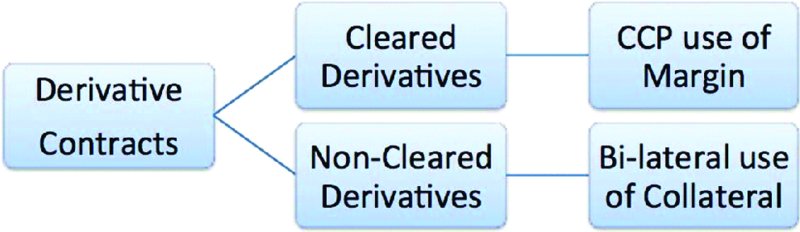

There are two generally accepted methods of mitigating this credit risk exposure depending on whether the derivatives transaction was exchange-traded (ETD) or OTC (OTCD). ETD transactions are typically margin-based and OTCD transactions tend to be collateralised. Now that there is the regulatory requirement to centrally clear OTCD transactions, it is perhaps more correct to refer to derivatives transactions that are either cleared through a CCP or non-cleared.

Figure 9.1

shows the situation before the enactment of DoddâFrank (USA) and EMIR (European Union) and

Figure 9.2

shows the situation afterwards.

FIGURE 9.1

Clearing before regulatory intervention

FIGURE 9.2

Clearing after regulatory intervention

Please note that some standardised OTCDs such as some interest rate swap products have been centrally cleared for a number of years.

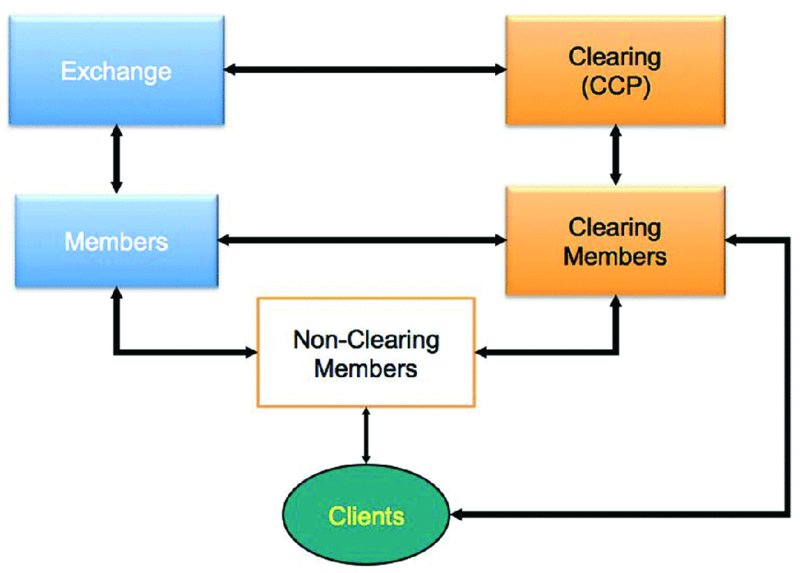

For exchange-traded contracts such as futures and options, the derivatives exchange and the clearing system may be either part of the same organisational structure or separate organisations. In either event, there will be good links between the exchange and the clearing system.

Members of an exchange may also be members of the clearing system. If not, they must have a non-clearing agreement with a clearing member.

Figure 9.3

shows the relationships between the exchange, the clearing system and their respective

members.

FIGURE 9.3

Exchange-traded derivatives

Members of an exchange can also be members of a clearing system and they submit trade details to the clearing system for clearance. If they only clear transactions for their own business, they are known as

clearing members

(or

individual clearing members

). If they also clear the business of non-clearing members (see below), they are known as

general clearing members

(GCMs).

Certain exchange members may choose not to be either CMs or GCMs. These organisations are known as

non-clearing members

(NCMs) and will either clear through a GCM or “give-up” the trade to a CM or GCM.

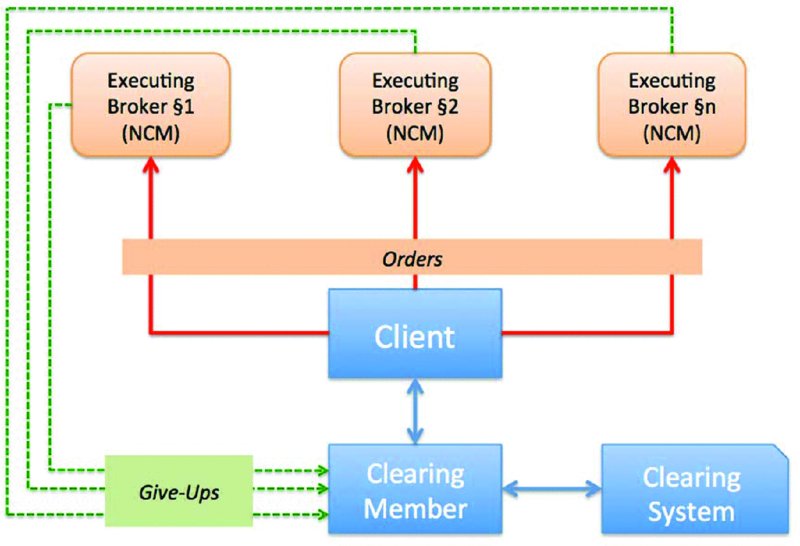

Where a client, its executing-only broker (the NCM) and CM/GCM have entered into a tri-party Give-Up Agreement, trades executed by the NCM are transferred (or given up) to the client's CM/GCM. In this way, the client is free to use multiple execution-only brokers but consolidate all the trades with the single CM/GCM, as shown in

Figure 9.4

.

FIGURE 9.4

Give-Up Agreements

The Give-Up Agreement (its full name is the International Uniform Brokerage Execution Services Agreement) was developed by the Futures Industry Association (

www.futuresindustry.org

) in 1995. Later, in 2007, the FIA implemented the Electronic Give-Up Agreement System (EGUS) which: “decreased the time (taken) to execute ⦠(a Give-Up) Agreement from an average of 39 days to 2 days”.

7

As soon as a CCP has registered a transaction, novation occurs and the CCP becomes the counterparty to the buyer and to the seller. To limit and protect itself from the default risk of a clearing member, the CCP collects margin on all open positions. Clearing members' margin positions are calculated either once a day or several times intra-day.

There are two types of margin: initial margin and variation margin.

- Initial margin (IM):

A deposit called by a CCP on all net open positions and returned when the positions are closed. Assets used for IM delivery can be eligible securities and cash. - Variation margin (VM):

A member's profit or loss on open positions calculated daily using closing mark-to-market prices. VM is treated either as realised (cash amounts are credited/debited to members' accounts) or unrealised profits or losses.

There are two approaches that can be taken: we can calculate margin for a single position or for a collection (or portfolio) of positions in similar classes of derivatives.

The

single position approach

is straightforward and should help you to understand the basic principles involved. Let us consider a fictitious futures contract with the contract specifications given in

Table 9.1

.

TABLE 9.1

Interest rates future â contract specifications

| Contract size | USD 100,000 | Nominal value of the underlying asset (e.g. a government security) |

| Tick size | USD 10.00 | Minimum price movement of 0.01% of the contract size |

| Initial margin | USD 2,000.00 | per contract |

The initial margin is the number of contracts multiplied by the IM amount per contract.

The variation margin is the difference in contract price multiplied by the tick size multiplied by the number of contracts.

TABLE 9.4

Margin analysis

| Debit | Credit | ||

| IM account | USD 20,000.00 | USD 2,000.00 | VM account |

| USD 18,000.00 | Bank account | ||

| USD 20,000.00 | USD 20,000.00 |

Here is an explanation of what happened throughout the three days:

Day 1:

The IM calculation is 200 contracts à USD 2,000.00 = USD 400,000.00.The position was opened at 138.00 and, at the close of business, revalued at 138.07. If the tick size is 0.01, there has been a gain of 7 ticks and the VM calculation is 200 contracts à 7 à USD 10.00 = USD 14,000.00.

- Day 2:

150 contracts have been sold at 138.12. The profit is 5 ticks (138.12 â 138.07), amounting to USD 7,500.00, and USD 300,000.00 of the IM are credited (150 contracts à USD 2,000.00). Finally, the close of business price is 138.15, resulting in a profit of 8 ticks and a VM credit amounting to USD 4,000.00 (50 contracts à 8 ticks à USD 10.00). - Day 3:

150 contracts are purchased at 138.20 and the total position of 200 contracts then closed out at 138.18. Overall, on the IM account there will be a net credit of USD 100,000.00

8

resulting in a final balance of zero. To calculate the VM on the closing trade of 200 contracts, you should compare the prices as follows:- 50 (part of sale of 200) @ 138.18 against the brought-down balance of 50 @ 138.15 (profit of 3 ticks).

- 150 (balance of sale of 200) @ 138.18 against the purchase of 150 @ 138.20 (loss of 2 ticks).

- 50 (part of sale of 200) @ 138.18 against the brought-down balance of 50 @ 138.15 (profit of 3 ticks).

The

portfolio position approach

considers the overall risk to a portfolio of derivative and/or securities and calculates a “worst case” loss that the portfolio might experience under different market conditions. These market conditions are altered by inputting changes to futures prices and, for options, implied volatility shift. The system used for this is the Standard Portfolio Analysis of Risk (SPAN) system, developed by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange

9

in 1988.

SPAN is widely used by many exchanges around the world, including Tokyo, London and Singapore.