Financial Markets Operations Management (35 page)

Read Financial Markets Operations Management Online

Authors: Keith Dickinson

Custody and the Custodians

Part Three of the book will take you through the post-settlement environment of safekeeping, asset servicing and asset optimisation.

We have seen in previous chapters that securities are generally no longer certificated; previously certificated securities tend to be either dematerialised or immobilised and newly issued securities might be represented by a single (global) certificate. This move has certainly helped to ensure that clearing and settlement are straightforward, as sales and purchases are represented by debits and credits across a securities account. We have also noticed that clearing systems, whether in the form of a clearing house or a central counterparty, play an important role. This leaves us with the question of how the securities are held in a safe and secure environment.

In much the same way that clearing and settlement take place centrally, so does the safekeeping (or custody) of securities. Securities issued in one particular domestic market will be held by the relevant local central securities depository. In this chapter we will therefore look at the relationship between the investor (i.e. the beneficial owner), the CSD and the intermediaries that sit between the investor and the CSD.

By the end of this chapter you will:

- Be able to define “custody”;

- Understand the forms in which securities are issued and the impact on their safekeeping;

- Know what a nominee is and how it can be used by the custodians;

- Appreciate the relationships between the beneficial owner, a local custodian, a global custodian and the CSD/ICSD;

- Understand the relationship between beneficial owner and custodian together with the products and services that are available.

There are two forms of securities. From a securities issuer's point of view, it either has to know or wishes to know who the owners of the securities are. In this case, the issuer (or more likely a third party appointed by the issuer) records the owners' details on a register. We refer to these asset types as

registered securities

.

By contrast, if the issuer is not obliged to know who the owners are, then it might issue securities that are in bearer form. In this case, ownership details are not required and will therefore not need to be recorded on a register. We refer to these asset types as

bearer securities

.

Registered and bearer securities display certain characteristics that need to be considered from an operational point of view.

Table 10.1

shows the characteristics of registered securities and

Table 10.2

those of bearer securities.

TABLE 10.1

Registered securities

| Registered Securities | Certificated | Non-Certificated |

| Ownership | Ownership evidenced by “name-on-register” (held by issuer's agent) plus the name is noted on the certificate. | Ownership is only evidenced by “name-on-register” (held by issuer's agent). |

| Issuer's agent | Known as a registrar or transfer agent. | |

| Change of ownership | Change of ownership is recorded by the registrar/transfer agent. Certificates are issued for increases in ownership (e.g. purchases) and cancelled for decreases (e.g. sales). | Change of ownership is recorded by the registrar/transfer agent. |

| Loss of certificate | A replacement can be obtained from the registrar for a fee plus a letter of indemnity. | Not applicable. |

| Communication from issuer to investor | Through registrar who maintains the list of investors (information “pushed” to investor). |

TABLE 10.2

Bearer securities

| Bearer Securities | Certificated | Non-Certificated |

| Ownership | No evidence of ownership on certificate. Ownership is evidenced by investor (or his agent) holding the certificate. Alternatively, a depository can hold 100% of an issue on behalf of its participants. | CSD maintains records of participants' holding as a result of settlement results received via the clearing process. |

| Change of ownership | Seller delivering certificate to buyer. | CSD amends records to reflect change. |

| Loss of certificate | Not possible to obtain a replacement. | Not applicable |

| Communication from issuer to investor | Issuer does not know its investors. It must therefore publish any communication and rely on the investor seeing it (information “pulled” by investor). |

In any securities transaction, ownership is transferred from the seller to the buyer. If we use a shopping analogy, the goods that you purchase belong to you and the cash that you pay belongs to the shopkeeper. I hope that you will agree that this is the case; but what makes it so? What evidence is there to prove that you do own the goods that you have purchased (and the shopkeeper owns the cash)?

As your name will not be noted on the goods, the only evidence that you are the owner is that these goods are under your control, i.e. in your shopping bag. If questioned by a third party (e.g. a security guard), you can demonstrate that you have purchased the goods by showing the till receipt. Your purchased goods are analogous to securities that are in bearer form. You will have noticed that the transfer of ownership was straightforward and only required the shopkeeper to hand over the goods to you.

It is no different for the cash side of the transaction. The cash has been placed in the till and a receipt issued to the purchaser. Neither you nor the shopkeeper will have written your names on the cash; again, cash is a bearer asset and is also fungible in nature. Fungibility occurs when

one unit of an asset is exactly the same as another unit of the same asset, e.g. a one euro coin is the same as any other one euro coin. Indeed, a EUR10 note is the same as ten one euro coins.

For bearer securities, transfer of ownership in a certificated environment is the delivery by the seller to the purchaser. In an un-certificated environment, transfer of ownership is achieved by debiting the seller's securities account and crediting the buyer's securities account.

The situation is slightly different for registered securities, as evidence of legal ownership rests with the issuer (or its registrar/transfer agent) and any change of ownership must be advised to the issuer. So, whilst a transaction for a registered security is no different from that for a bearer security, there is an extra step in the process that needs to be considered.

If we continue with our shopping analogy, say you had purchased some computer software and had paid for it in the expected manner. Once you have loaded the software onto your computer, you might be expected to register the software with the publisher. This usually involves entering your personal details and an activation code containing an alphanumeric character sequence. In effect, you have told the software publisher that you are the licensed owner/user of that software. In a registered securities context, you have told the issuer of the securities that you are now the owner of the securities. Unlike the software analogy, in order for the buyer to take ownership, the seller has to surrender ownership. This is done through a legal document known as a

stock transfer form

(STF). The STF authorises the issuer's registrar to reflect the change of ownership on the share register. The seller completes the top half of the form and the buyer the bottom half.

On the share register, the entries shown in

Table 10.3

would be made for a sale of 500 shares.

TABLE 10.3

Share register entries

| Owner | Existing Holding | Increase | Decrease | New Holding |

| Seller | 1,500 | â500 | 1,000 | |

| Buyer | 2,000 | 500 | 2,500 | |

| Totals: | 3,500 | 500 | â500 | 3,500 |

The same principle applies for un-certificated registered securities; entries over the share register remain the same. The main difference is that there is no requirement to surrender share certificates and complete the stock transfer form as above. Instead, once the transaction has been settled, the securities settlement system electronically informs the registrar of the change of ownership. This electronic advice replaces the stock transfer form.

To summarise, depending on market practice, owners of registered securities can either hold physical securities with their names recorded on the issuer's share register or statements from the issuer denoting the quantity of securities owned.

Investors with securities registered in their own names have a direct stake (share) in the issuer. This type of ownership enables the issuer to communicate directly with the investors.

Operational complications can arise if the owner decides to ask a third-party custodian to hold their securities on their behalf. This will not be a problem for bearer securities but will be for registered securities, as the following examples illustrate:

- The owner wishes to sell some or all of his holding. The owner will request his broker to execute the sale and request his custodian either to deliver the physical securities or electronically transfer the securities to the broker. If the securities are in physical form, this will require a stock transfer form to be completed by the owner and delivered to his custodian. This can take time and might lead to a delay in the settlement process.

- The issuer sends a communication to the owner and requires a response. This communication will be sent to the owner at the address recorded on the register. The custodian will not be aware of this and may not be in a position to help the owner if a problem arises.

- If the owner has a problem (e.g. a dividend has not been received), he has to contact the issuer. His custodian may not be able to investigate on his behalf, as the issuer would only recognise the owner and not the custodian.

From these three examples you might correctly assume that the custodian will have operational issues when holding securities for owners that are registered in the owners' own names. There are alternative ways that owners can hold their securities:

- Re-register the securities in the name of the custodian.

- Re-register the securities in the name of a nominee managed by the custodian.

We will look at these in turn below.

If the owner decides to re-register his securities in the name of his custodian, legally he is surrendering ownership to that custodian. Now the issuer communicates directly with the custodian and no longer with the original owner. From an operational point of view, this change would enable the custodian to settle and administer the securities. It only requires a single instruction/communication with the owner rather than potentially several which the above examples might require.

The biggest risk for the owner, however, is that the custodian is now the legal owner of the securities and if the custodian were to default, it might be difficult or impossible to demonstrate that the custodian's customer was, in fact, the legal owner.

What is required is the separation of legal ownership from beneficial ownership. Where the owner's name is on the shareholder register, both types of ownership are combined. The objective is to enable the owner to retain beneficial ownership and the custodian to obtain legal ownership. This is where the concept of a nominee account comes in.

Having stocks recorded in the investor's own name at the central securities depository is uncommon, but not impossible, in most countries. There are some exceptions, such as in Singapore, where most local brokerage accounts require investors to have their own account at the central depository (CDP), or in the UK, where the process of having a personal account at CREST is straightforward, if rarely done by most investors.

A nominee company is a legal entity in its own right, with its own share capital, Memorandum and Articles of Association together with a Company Secretary. In essence, a nominee company is no different from any other type of company and is legally separate from the custodian. This distinction is important because, in the event of the custodian defaulting, the nominee company remains as a going concern.

The Company Secretary and the authorised signatories will be members of staff of the custodian. The nominee company cannot itself default because it does nothing: it does not lend money, it does not invest, it does not take risk, etc. All that a nominee company is established to do is to act as a “flag of convenience”, which, in this context, means that it acts as the legal owner of securities with its name recorded on the shareholder register.

In terms of legal ownership, therefore, securities registered in the custodian's name have the same legal status as securities registered in the name of the nominee company. The big difference is the separation of the custodian's risk of default.

Using a nominee company enables the custodian to keep safe and administer its customers' securities to its maximum efficiency. The custodian's customer retains beneficial ownership and therefore receives dividends in the usual way, albeit paid by his custodian rather than the issuer. The customer does, however, lose the direct relationship with the issuer that they would have had had their own name been recorded on the shareholder register.

What name should the custodian give its nominee company? To avoid any potential legal confusion, it is usually not a good idea to have the name of the custodian contained within the name of the nominee company. For example, when the author worked for Barclays Bank International in the 1970s, the branch address was 29 Gracechurch Street, London EC3. The branch operated a nominee company: “29 Gracechurch Street Nominees Limited” and customers' registered securities would have been registered in this name.

There are two ways in which a nominee company's name can be used:

- Omnibus (pooled) account.

- Segregated (designated) account.

In an omnibus account structure, all the customers' securities are registered in the name of the custodian's nominee company, for example, Wharfedale Nominees Limited, as listed in

Table 10.4

.

TABLE 10.4

Omnibus nominee account

| ABC, Ordinary Shares (registered in a single nominee name) | ||

| Customer | Customer Holding | Registrar Holding |

| Customer 1 | 10,000 | |

| Customer 2 | 15,000 | |

| Customer 3 | 20,000 | |

| Customer 4 | 25,000 | |

| Customer 5 | 30,000 | |

| Total: | 100,000 | 100,000 |

The following points should be noted:

- All five customers beneficially own a total of 100,000 shares, with each customer's shares commingled within the omnibus account.

- The registrar has 100,000 shares recorded on its shareholder register, with the legal owner being the nominee company.

- If a dividend is paid by ABC of GBP 1 per share, the issuer's paying agent will pay the nominee company GBP 100,000 and the nominee company will apportion that single dividend payment across each of the customers' cash accounts in proportion to their holdings.

- If, for example, Customer 4 sells its holding of 25,000 shares, there will be sufficient shares in the account from which to make a delivery.

As an alternative to the omnibus account structure, customers can request that their securities are held separately from other customers. In this case, the securities will be registered in several nominee names; the name of the nominee company remains the same, but a designation is added to that name. In this case, there

will be many accounts held by the registrar (as opposed to a single account in the omnibus structure).

If we consider the five customers above, we might have the situation shown in

Table 10.5

.

TABLE 10.5

Designated nominee account

| ABC, Ordinary Shares (registered in multiple nominee names) | |||

| Customer | Customer Holding | Name on Register | Registrar Holding |

| Customer 1 | 10,000 | Wharfedale Nominees Limited sub account: A01 | 10,000 |

| Customer 2 | 15,000 | Wharfedale Nominees Limited sub account: A02 | 15,000 |

| Customer 3 | 20,000 | Wharfedale Nominees Limited sub account: A03 | 20,000 |

| Customer 4 | 25,000 | Wharfedale Nominees Limited sub account: A04 | 25,000 |

| Customer 5 | 30,000 | Wharfedale Nominees Limited sub account: A05 | 30,000 |

| Total: | 100,000 | 100,000 |

The following points should be noted:

- All five customers beneficially own a total of 100,000 shares, with each customer's shares registered in the same nominee name but with a unique designated sub account.

- The registrar has five separate accounts holding each customer's shares and totalling 100,000 shares.

- If a dividend is paid by ABC of GBP 1 per share, the issuer's paying agent will pay the nominee company five amounts of GBP 10,000, GBP 15,000, GBP 20,000, GBP 25,000 and GBP 30,000 respectively and the nominee company will credit the dividend payments across each of the customers' cash accounts.

- If, for example, Customer 4 sells its holding of 25,000 shares, there will be sufficient shares in its designated account from which to make a delivery.

So far, we have considered the nominee concept from the point of view of the custodian (or indeed any firm such as a broker that might act in the capacity of a custodian). From the issuer's point of view, there will be many different names of nominee companies in both omnibus and designated forms.

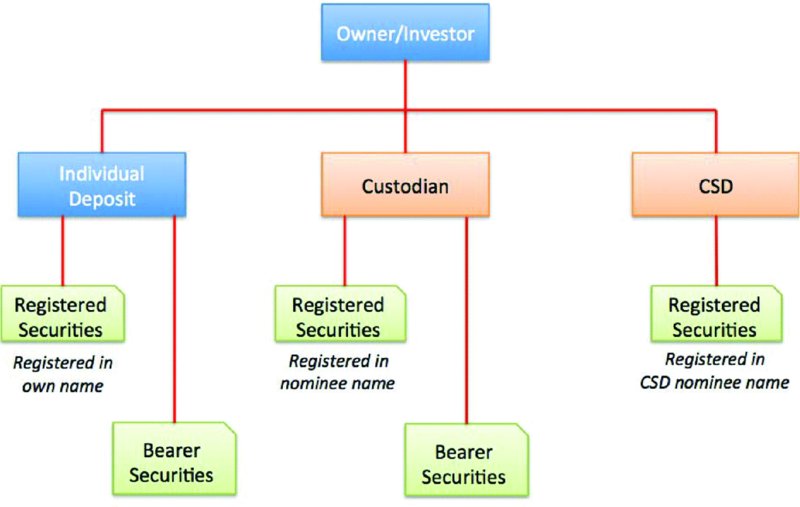

There are markets where the CSD maintains a nominee name and registers securities in this name.

In the USA, the CSD operates street name securities. In principle, street names are similar to nominee names, in that the street name is recorded on the share register and is the legal owner (with the investor as the beneficial owner). The name used by the Depository Trust & Clearing Company is “Cede and Co.”

In countries where it is not possible to use a nominee account structure, investors might only be able to register their securities in either their own name or in the name of their custodian.

Figure 10.1

summarises the ways in which an owner/investor might hold their securities.

FIGURE 10.1

Holding securities â summary