Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (102 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

9.24Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

a functional concept

a wellbeing concept.The medical concept of health refers to the absence of illness and is characterised by the avoidance and destruction of pathogens and the slowing or prevention of disease progression. This is the predominant understanding of UK health service personnel (Bowden 2006). This is a mechanistic or biomedical approach to health, in which the body is a machine that needs repair and maintenance. Diseases are defined as disruptions in bodily systems or organ structure with characteristic signs and symptoms, aetiological agents and anatomical changes (Porth 2009). Poor health, in this system, is purely physical, measurable and treatable. Clarke (2011) creates two categories in the medical concept of health:

The

absence of clinically verifiable disease

: diagnosis dwells on biophysical abnormalities (Martin 2010; Clarke 2011).

absence of clinically verifiable disease

: diagnosis dwells on biophysical abnormalities (Martin 2010; Clarke 2011).

The

absence of illness

: focusing on subjective perceptions – symptoms (Martin 2010; Clarke 2011).

absence of illness

: focusing on subjective perceptions – symptoms (Martin 2010; Clarke 2011).

However, as early as the mid-20th century, the model was shown to be incomplete. The World Health Organization (1948) adopted a broader definition of health calling it:

. . . a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

This is idealistic (Porth 2009), encompassing bodily, psychological and social contexts of life and has been criticised for lacking any real meaning and being ‘hopelessly utopian’ (Mordacci and Sobel 1998, p. 34); simultaneously, totally comprehensive and meaningless (Lewis 1953). It may be more desirable to use definitions of health which extend beyond biophysical parame- ters but which relate realistically with people’s lived experiences and aspirations.

‘

Functional health

’ is the ability to practically function within society (Bowden 2006), viewed from the perspective of either the individual or society (Clarke 2011). This is found in the ‘

social model of disability

’ discourses, which emphasise the cooperative actions of society in removing disabling factors from within it, above individual impairment (Oliver 1983). A functional concept of health might be defined by a person’s ability to engage in the activities of daily living (Cham- berlain and Gallop 1988), which may be achieved by people with chronic ill-health, such as bronchial asthma or type-I diabetes mellitus, with appropriate management.

Western medicine has recently experienced a shift towards more holistic thinking, relating bodily function to the mind and soul (Tiran 2008; Martin 2010). Health is conceptualised as wellbeing, or ‘feeling good about yourself’ (Bowden 2006). Illness is possible in the absence of a biophysical disease: clinical dysfunction is possible in the absence of subjectively experienced illness (Mordacci and Sobel 1998). Wellbeing encompasses individuals’ experiences of central wholeness and harmony, regardless of biophysical diagnoses and harnesses physiological, psy- chological and spiritual aspects (Guttmacher 1979).

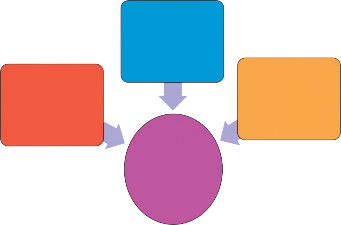

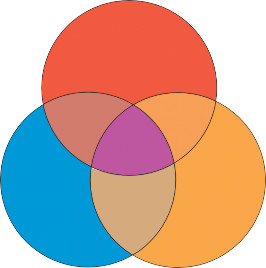

Health could be viewed as any one of these three concepts (see Figure 11.1). Beldon and Crozier (2005) argue that midwives tend to prefer holistic concepts of health, which could be represented as the sum of all three aspects (see Figure 11.2), or possibly the intersection between the three (see Figure 11.3).

239

Functional

Medical

Wellbeing

Health

Figure 11.2

Diagram representing how different Concepts of Health contribute to the overall concept (adapted from Bowden, 2006).

Medical

Health

Functional

Wellbeing

240

Figure 11.3

Venn diagram showing health as the intersection between the three concepts (adapted from Bowden, 2006).

Public health

Public health has been defined as:

. . . The science and art of promoting and protecting health and well-being, preventing ill- health and prolonging life through the organised efforts of society . . .

(UK’s Faculty of Public Health 2010)

This is:

. . . inclusive of all interventions designed to improve the health of the public . . .

(Wanless 2003, p. 49)

Public health requires whole societal involvement, harnessing individual choices, capabilities and actions, in partnership with health services. Prolonging life implies progressive improvements inasociety’shealth. Historically, scientific research, innovationanddissemination, publicsanitation, healthcare developments, social welfare, social reform and legislation, have all contributed to public health improvements (Sydenstricker 1935; McCormick 1993). General Secretary of the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), Audrey Wood (1957) identified British midwives’ public health role through antenatal care as having had a major role in preventing prematurity, stillbirths and neona- tal deaths. The RCM (2001) position paper on the Midwife’s Role in Public Health responded to the prevailing policy direction of the National Health Service (NHS) (DH, 2000). Public health incorpo- rates social and political factors, not just individualistic medical perspectives, exploring the roots and causes of health and ill health in populations (RCM 2001; Martin 2010).

Epidemiology

Epidemiology, literally, ‘

studies upon people

’ is foundational to public health (Farmer et al.

2004; Omran 2005). Epidemiology traces how disease and ill-health is distributed through

populations, discovering influencing factors, measuring, reporting and interpreting the causes of disease (morbidity) and death (mortality) (Farmer and Lawrenson 2004; Gordis 2009). Epide- miology informs the prevention of the spread of disease and the control of societal health problems (Carr et al. 2007). Puerperal sepsis (childbed fever) was a major cause of maternal mortality in the early 19th century (Gordis 2009). Ignaz Semmelweis (in Austria) and Florence Nightingale (in England) were instrumental in demonstrating the links between place of birth, hygiene, caregivers’ practices and rates of maternal mortality from puerperal sepsis, contribut- ing to its significant decline (Nightingale 1871; Dunn 1996; Gordis 2009).

Demography

Demography

measures populations, providing records of size, location and characteristics, such

as age, gender, social class, migration and ethnicity (Bowling 2009; Martin 2010), which is essen- tial for effective planning of health services and guiding public health interventions. Maternity statistics include conception rates, fertility rates, birth rates, maternal and infant mortality rates. The National Health Service Act (1977) requires births to be notified within 36 hours to the relevant area Director of Public Health by a midwife or doctor in attendance. Birth registration must be conducted within 42 days of birth by the parents or midwives (and others classified as owning the premises) if the child’s parents have not done so (Sidebotham and Walsh 2011).

Conception rates

Conception statistics include pregnancies that result in one or more live births, stillbirths or a

legal abortion under the Abortion Act 1967. They do not include miscarriages or illegal abor- tions. These relate to women of childbearing (age 15–44 years old), who could give birth in any year (Office for National Statistics (ONS) 2012a).

Fertility rates

The

General Fertility Rate

(GFR) equates to ‘ . . . the number of children per 1000 women born to

a population or sub-population’ (ONS 2012a, p. 7). For example, a GFR of 56 in 2007 for the UK means that for every 1000 women of childbearing age in the UK, 56 babies were born. The

Total Fertility Rate

measures the average number of children that a group of women would each have if they experienced the age-specific fertility rates for a particular year throughout their child- bearing lives. For example, a TFR of 1.90 in 2007 means that a group of women would have an average of 1.90 children each during their lifetimes based solely on 2007’s Age-specific Fertility Rates (ONS 2012a).

Age-specific Fertility Rates (ASFR)

are measures of fertility specific to the age of the mother obtained by dividing the number of live births in a year, to mothers in each age group, by the number of females in the mid-year population of that age, these are expressed per 1000 women in the age group (ONS 2012a).

Birth and death statistics

Live birth

refers to a baby born, showing spontaneous signs of life after birth regardless of ges-

tational period (ONS 2012b; WHO 2013). Figure 11.4 shows the number of Livebirths in the England and Wales over a 50 year period (between 1961 and 2011). Other statistics quantify maternal and infant deaths, which are important for discovering risks and identifying preventa- tive strategies (Table 11.1).

Other books

Forever by Chanda Hahn

Waiting for Cary Grant by Mary Matthews

Dagger - The Light at the End of the World by Walt Popester

Butterfly Lane by T. L. Haddix

Land of the Free by Jeffry Hepple

Light and Wine by Sparrow AuSoleil

The Devil by Ken Bruen

The Indigo Pheasant: Volume Two of Longing for Yount: 2 by Daniel A. Rabuzzi

Bewitched, Bothered, and Biscotti: A Magical Bakery Mystery by Bailey Cates

My Obsession by Cassie Ryan