Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck (32 page)

Read Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck Online

Authors: Amy Alkon

By diminishing patients’ anger and desire for revenge, the medical center also avoids prolonged and expensive court battles, which cost the government approximately $250,000 per case to defend. They now resolve more cases in across-the-table settlement meetings with just an attorney, a paralegal, and a few other hospital employees present.

Back in my world, a woman who hit and damaged my parked car also managed to stay out of court—unlike the nasty old man who’d previously sideswiped my parked car and thought he’d gotten away with it. (After I went Nancy Drew on his ass, tracked him down, and petitioned the city attorney to prosecute him, he not only had to pay to fix my car but also did a day of jail time.)

Upon seeing the damage the woman did to my car, I would have been my usual relentless self: putting up fliers on phone poles, walking the neighborhood to seek witnesses, requesting video footage from neighbors with surveillance cameras. Except … she left this note on my windshield: “I scraped your car while backing out. Very sorry. Here’s my number. Please call and I will pay to fix.”

I meant to call. And I kept meaning to call. But, there’s nothing like a satisfying apology—full accountability followed by an offer to make good with cash—to keep a girl off her broom. Without any need to

make

her pay, even picking up the phone to

ask

her to pay kept sinking lower and lower down my to-do list … until it finally just slipped off.

TO BE HUMAN IS SOMETIMES TO BE AN ANGRY ASSHOLE

Sometimes, your anger at something somebody’s said or done will just get the best of you. Even if that somebody is only landing verbal punches, the message that you’re being attacked gets dispatched to the brain, jumps on the amygdala’s anger train—bypassing reason—and launches you into that adrenaline-driven “fight” part of the fight-or-flight reaction.

Reminding yourself of the process before you get into a conflict could possibly help you pull back when some interaction starts to get heated. You disengage by pausing and switching gears entirely: saying something like “I’m sorry. I’m behaving badly. Can we start over?” Remember also that you can sometimes help the other person mitigate how you’ve been behaving by offering an explanation (such as your already being upset over a flat tire or bad news) to support your contention that you don’t think they deserve to be barked at; you just let your bad mood push you in a direction it shouldn’t have.

At the time, they might be too far gone on the anger train to say anything other than “Fuck you!” but there’s a good chance that upon cooling down, they’ll reflect on your attempt to pull back and recognize the goodwill behind it, as well as how counterproductive it is to remain in a small-scale state of war. To further encourage such pacifying thoughts, you could make another goodwill gesture in a few hours or days. Say the ugliness was between you and a neighbor. You might leave a bottle of wine or a vase of flowers from your garden and an apology note on their porch. If more discussion is needed, you could ask them to meet you for coffee and a friendlier chat to work out a solution that works for both of you.

Don’t treat grudges like beloved pets.

When somebody’s remorseless about injuring you, it’s wise to be mindful of the need to keep your distance while also accepting that what’s done is done. However, when somebody who’s wronged you shows you that they are genuinely sorry and gives you reason to believe they mean it and won’t repeat their behavior, it’s time to scrub their name from the no-fly list in your brain and shoo away your bad feelings about them.

Clinging to being wounded is like dragging around a giant bag of dirty laundry on one of those big iron chains from a ship. In other words, it probably does “hurt you as much as it hurts them.” To release a grudge, you simply resolve to go forward and inform the person you’re doing it by saying or writing, “Apology accepted. I’m going to forget this happened, and we can move on from here.”

Help other people make good.

Sometimes, somebody wrongs you because they’re a mean-spirited turdblossom who lives to induce pain. But sometimes, a person just gets sloppy; they are stressed and tired and didn’t give enough thought to how they were treating you.

When this could be the case, you might give the person a chance to make good by gently informing them that they hurt you and possibly by adding what you think would have been a kinder approach. As I’ve said elsewhere in this book, it’s usually best to do this in writing rather than in person, as it helps the person save face, minimizes defensiveness, and gives them time to consider what you’re saying. And even if you get no response or an unsatisfying response, your taking positive action—telling the person they’ve wronged you—is how you yank yourself out of the victim’s seat and keep from dragging a grudge around.

About a year and a half ago, one of the elders of behavioral science hurt my feelings. I have long had great respect for his work and even admired him as a human being. We’d communicated a number of times over the years, with my emailing him letters of appreciation about his work a couple of those times, and I had also written about his research and frequently recommend his books to readers who write me for advice.

This time, I had emailed him to invite him on my science-based radio show to discuss his most recent book. I would have accepted it just fine if he’d turned me down, giving me any remotely plausible excuse. But the way he did respond—just “Sorry, I cannot”—made me feel bad for over a year, so I finally emailed him. I told him that I had always thought very highly of him and hated that whenever I saw one of his books on my shelf, I’d flash on his curt reply and my disappointment that he, of all people, had been unkind to me. I went on to write:

Maybe you weren’t feeling well or thought my show probably wasn’t worth the time. I accept that you may have thought that. But I just wanted to suggest, respectfully, that responding so curtly is what conflict resolution specialist Dr. Donna Hicks explains as a dignity violation—treating someone as if they have no value.

I often have to turn down people who ask me things I don’t have time for, but even if I think they’re crackpots, I pretend otherwise when I write them. It takes just a few extra moments to preserve somebody’s dignity, to say, “I’m so sorry, I wish I could, but I’m extremely busy with research, etc.” Whether that’s true is immaterial. It’s kind. It allows the person to believe “it’s not me; it’s just that there isn’t time…”

I have great respect for you and great gratitude for all the work you’ve done and the foundation it’s laid for all who carry on with the research. I just needed to stop thinking of that curt reply from you every time you and your work come to mind and I thought this might help me change the channel.

All the best,

Amy Alkon

His reply was all it took to release me from bad-feelings jail:

You are right, of course, and I apologize.

>

He continued that he gets about five such invites a day from journalists and only does about one interview every six months. He added:

… and I am a one finger typist.

>

>

But I will try to take your advice, even though it means quite a few

>

extra hours typing per month.

>

>

Thanks for bringing me up short on this.

>

>

all the best

I hated to think of him wasting science time on typing. I wrote back, suggesting a macro program so he could type a single code word and hit

RETURN

to drop already-created statements into e-mail, which he could personalize with just a “Dear So-and-So.”

His reply:

very helpful, I’ll try this out.

Very helpful indeed. Now, instead of hurt feelings, I again have warm feelings about him and sometimes a little laugh at the thought of him pecking away, one-fingered, at his keyboard.

TRICKLE-DOWN HUMANITY

The pursuit of happiness

is the wrong way to go about getting it. Of course, that’s not what we’re led to believe. America is all about pursuing happiness. It’s written right into our Declaration of Independence as something we have an “unalienable” right to do. But positive psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky and other happiness researchers find that what many of us think will boost our happiness—getting a raise or a clean bill of health, buying a new car or a new set of boobs—can make us happier, but

not much happier

and not for very long. As the novelty of the bigger boobs wears off or we get used to the idea that we aren’t sick after all, we go right back to being however happy or unhappy we were before.

Even big, important life events don’t come with the happiness boost we’re led to believe they will. Psychologist Richard Lucas did a massive study that found that getting married leads to only a two-year bliss-bump, on average, before spouses slide back to their pre-engagement level of happiness or unhappiness. Yes, it seems that even “happily ever after” comes with an expiration date.

The good news is, “

meaningfully

ever after” seems to have legs. In 1945, upon being liberated from a Nazi concentration camp, Viennese psychiatrist and neurologist Viktor Frankl wrote

Man’s Search for Meaning

, originally published in German as

Saying Yes to Life in Spite of Everything: A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp

. Frankl wrote about the horrors and inhumanities of the camps, but the book centers around his observations on how essential finding meaning seems to be, in living a satisfying life and even in having the will to go on.

Frankl recalled that two of his fellow prisoners who’d expressed their intention to kill themselves “both used the typical argument—they had nothing more to expect from life.” Getting them to change their minds took getting them to realize that they still had something meaningful to live for. For one, it was his child who was waiting for him in a foreign country. The other was a scientist whose series of books still needed to be finished. “His work,” Frankl wrote, “could not be done by anyone else, any more than another person could ever take the place of the father in his child’s affections.”

To understand how meaning relates to happiness, it’s important to understand that being happy doesn’t necessarily mean getting into a cheery mood. Sure, feeling cheery is a kind of happiness, but a deeper, more sustaining happiness is an overall sense of well-being and satisfaction with your life. In Frankl’s words, this sort of happiness “cannot be pursued; it must ensue.” He went on to explain that “it only does so as the unintended side effect of one’s dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the byproduct of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself.”

It’s kind of amazing that we, as self-interested beings, would be so outwardly directed in what gives us the will to go on. But Frankl’s thinking

55

has been supported by research in recent years by Lyubomirsky, social psychologists Roy Baumeister and Kathleen Vohs, and many others. These studies repeatedly confirm that the way to personal fulfillment is through our relationship with and positive effect on others.

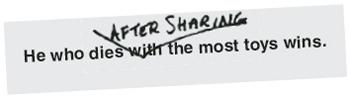

Don’t mistake this as an argument for asceticism. I’m not suggesting that you give away everything you have and shuffle the streets in cardboard sandals, and I don’t think you’re a bad person if you want a Ferrari and a thirty-room mansion with a moat. But if you also want to be successful at being happy, the bumper sticker on the back of your Ferrari should probably be something like:

HOW TO LIVE MEANINGFULLY

Living meaningfully means being bigger than just yourself. It means making the world a better place because you were here. It is possible to do this through your job, especially if your work involves helping others but even if it does not.

In

Practical Wisdom

, psychologist Barry Schwartz writes movingly of Luke, a janitor at a teaching hospital who cleaned the room of a man’s comatose son twice in short order. The patient’s father, who had been keeping a vigil by his son’s bedside for months, had been out on a smoke break when Luke first cleaned the room. On his way back, he passed Luke in the hall and, in Luke’s words, “just freaked out,” accusing him of not cleaning the room.

“At first I got on the defensive, and I was going to argue with him,” Luke said. But he caught himself. He’d heard that the son had been in a fight, had gotten paralyzed, and would never come out of his coma. Instead of snapping back, Luke simply said, “I’m sorry. I’ll go clean the room.” And then he went in and cleaned it again so the father could see him doing it.