Languages In the World (23 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

Arabic has a regular process of forming plurals with suffix -

Å«n

for masculine nouns and -

Ät

for feminine nouns:

muÊallim

âteacher (male)' versus

muÊallimÅ«n

âteachers (male)' and

maktabah

âlibrary' and

maktabÄt

âlibraries.' However, there is another process known as

broken plurals

that is both distinctive in Arabic and widespread. It is found in other Semitic languages but is in the most evidence in Arabic, and it is found in other languages that have borrowed heavily from Arabic through Islamicization, namely Azerbaijani, Kurdish, Pashto, Persian, Turkish, and Urdu.

The pattern-templates are many and nearly unpredictable:

| Singular form | Plural form | Example | |

| CiCaC | kitÄb âbook' | kutub âbooks' | |

| CaCÄ«Ca | CuCuC | safÄ«na âship' | sufun âships' |

| CaCÄ«C | sabÄ«l âpath' | subul âpaths' | |

| maCCaC | maCÄCiC | maktab âoffice' | makÄtib âoffices' |

| maCCiC | masjid âmosque' | masÄjid âmosques' |

(Can you guess what the triliteral root s-j-d means?)

| CÄCiC | CuC 2 C 2 ÄC | kÄtib âwriter' | kuttÄb âwriters' |

| á¹Älib âstudent' | á¹ullÄb âstudents' | ||

| miCCÄC | maCÄCÄ«C | miftÄħ âkey' | mafÄtīħ âkeys' |

| maCCÅ«C | maktÅ«b âmessage' | makÄtÄ«b âmessages' |

These examples are only a taste of the variety of the so-called broken plurals in Arabic. They give the language part of the complexity for which it is justly famous and often revered.

We said in Chapter 3 that the H/L linguistic situation in the Arabic-speaking world is known by the term

diglossia

and that it is a common enough occurrence throughout the world. To take but one example, in Haiti the L Kreyòl Ayisyen (see Final Note, Chapter 8) is opposed to the H Standard French.

In the Arabic-speaking world, diglossia is particularly complex because of the size of that world. On the one hand, the L varieties share common deviations from the Classical norm, from general trends such as the loss of case endings and the loss of the dual in the verbs and the pronouns to specific similarities such as the replacement of Classical

ra'Ä

with

Å¡Äf

âto see' (Versteegh 1984:17). Perhaps the most salient difference between H and L is the fact that H MSA is VSO, while the L varieties are SVO.

On the other hand, the L varieties also differ from one another phonologically and grammatically, as well as lexically. The lexical differences are due to the languages with which the L varieties have come into contact over the centuries. In North Africa,

for instance, L varieties have borrowings from French. Of the L varieties, Egyptian is the most widely understood not only because it is in the geographic center of the Arabic-speaking world but also because the products of its television and film industry are popular.

How and why did this diglossic situation arise? The short answer lies in the linguistic effects of the spread of Islam following the death of the prophet in 632. The next question is: What was the linguistic situation in the Arabic-speaking world

before

the spread of Islam? The pre-Islamic period is known as the

Jahiliyyah

, or Period of Ignorance. The word comes from the root j-h-l âto be ignorant, act stupidly' and produces, among other words,

jahl

âignorance' and

jahaalah

âfoolishness.' In the Jahiliyyah, it is believed that the tribes on the Arabian peninsula spoke different varieties of Arabic. Although no one knows the precise extent of the differences among the varieties, these differences do not seem to be great. There was an intertribal variety often referred to as a

poetic koine

that was used for poetry and prophecies and the like. The existence of this variety, however, does not offer evidence that it was used as a separate level, or register, of language. In other words, before Islam there was no diglossia.

In the first centuries after the spread of Islam, Arabic underwent a rapid change when the language of the nomadic Bedouin (

al-'Arab

) spread far and wide and into cities with their diverse populations and languages. It is the thesis of Arabic scholar Kees Versteegh (1984) that the features of this New Arabic, the basis of today's L varieties, show effects of creolization as converts to Islam â and therefore to the Arabic language â began to change the language. For the point being made here, what is important to note is that commentators and grammarians in the early centuries of the Islamic period became alarmed by the ways these new converts were changing the language, and these changes necessarily threatened to affect the recitation of the Qur'Än. Thus, the establishment of a Classical norm was necessary. Well over 1000Â years later, that norm is generally referred to as MSA. In other words, before Islam there was no diglossia, because there was no need for it. The need was created by the success of the Islamic conquest.

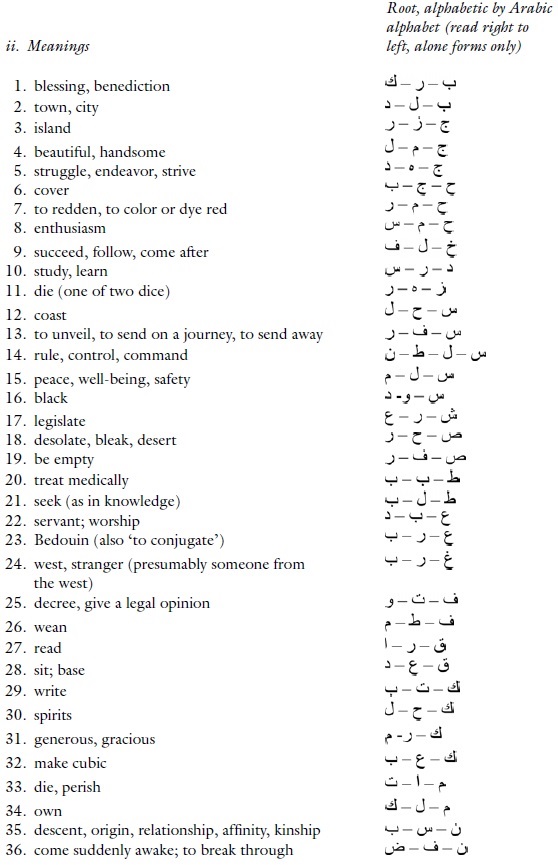

Determine which Arabic word in Part ii Meanings, below, is the source for the following words. You may write in either the number of the Arabic root or the Arabic letters themselves:

| Trilateral root | ||

| i. Alphabetic according to the Roman alphabet | transliterated | Arabic root |

|  1. Abdul | Ê â b â d | |

|  2. (al)cohol | k â ħ â l | |

|  3. (Al) Jazeera | ʤ â z â r |

Â

| Trilateral root | ||

| i. Alphabetic according to the Roman alphabet | transliterated | Arabic root |

|  4. (Al) Ham(b)ra | ħ â m â r | |

|  5. Arab/Arabic | Ê â r â b | |

|  6. baraka (French slang for âgood luck') | b â r â k | |

|  7. blède (French slang for âpodunk') | b â l â d | |

|  8. caliph | x â l â f | |

|  9. cipher (also French chiffre ânumber') | á¹£ â f â r | |

| 10. cube | k â Ê â b | |

| 11. Fatima (a woman's name) | f â á¹ â m | |

| 12. fatwah | f â t â w | |

| 13. Hamas | ħ â m â s | |

| 14. hazard | z â h â r | |

| 15. hijab (look it up, if you don't know) | ħ â ʤ â b | |

| 16. Intifada | n â f â Ḡ| |

| 17. Islam | s â l â m | |

| 18. Jamil (a man's name) | ʤ â m â l | |

| 19. jihad | ʤ â h â d | |

| 20. Kaaba (the sacred shrine) | k â Ê â b | |

| 21. Kareem | k â r â m | |

| 22. kitap (Turkish for âbook'); kitabu (Swahili for âbook') | k â t â b | |

| 23. Madrassa (religious school) | d â r â s | |

| 24. Maghreb (look it up, if you don't know) | Ê â r â b | |

| 25. maktaba (Arabic for âlibrary') | k â t â b | |

| 26. matador (borrowed from Spanish) | m â Ê â t | |

| 27. mate (as in âcheck mate') | m â Ê â t | |

| 28. Melek (âking' as in Melek Rik=Richard the Lionheart) | m â l â k | |

| 29. Mujahedin | ʤ â h â d | |

| 30. Muslim | s â l â m | |

| 31. nisba (a linguistic term â does anyone know it?) | n â s â b | |

| 32. (al)Qaeda | q â Ê â d | |

| 33. Qur'an | q â r â Ê | |

| 34. Sahara | á¹£ â ħ â a | |

| 35. Safari | s â f â r | |

| 36. Salaam | s â l â m | |

| 37. sharia (look it up, if you don't know) | Ê â r â Ê | |

| 38. Sudan | s â w â d | |

| 39. Sultan | s â l â á¹ â n | |

| 40. Swahili | s â ħ â l | |

| 41. Taliban | á¹ â l â b | |

| 42. toubib (French slang for âdoctor') | á¹ â b â b | |

| 43. zero (same as âcipher') | á¹£ â f â r |

Â

A recent study in the journal

Psychological Science

(Mueller and Oppenheimer 2014) shows that writing the old fashioned way â with pen and paper â boosts memory and the ability to retain concepts more than typing with a laptop. First, read the article. Then, consider the findings in light of what you read about the language loop in Chapter 2 and about writing in this chapter. Write a paragraph describing what the role of writing in the language loop may be, as it pertains to human cognition.

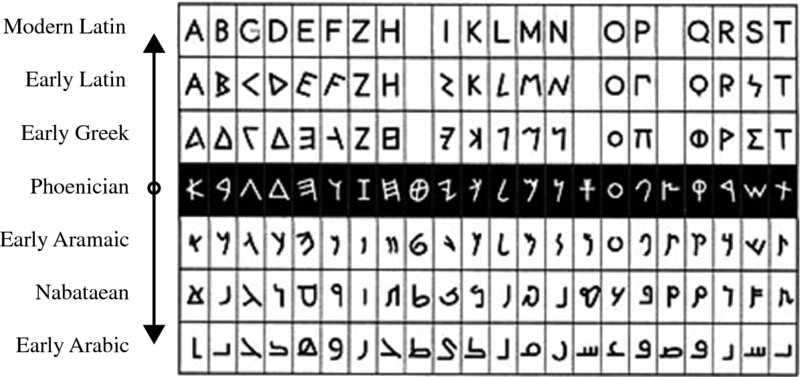

Examine

Figure 5.1

, depicting the development of the modern Latin alphabet from the first Phoenician alphabet. In what ways did the Greeks adapt the Phoenician script for their own language? What is Etruscan and where was it spoken? What types of adaptations did they make for their language? Finally, what types of adaptations did the Romans make when adapting Greek to Latin?

Figure 5.1

Genealogy of alphabets.

The Latin alphabet is the single most used alphabet used to write the languages of the world today. Many languages have adapted it to suit the needs of their unique phonetic inventories. Sometimes, this involves deleting or adding letters, while other times, it involves adding diacritic marks to existing letters. Make a table of 10 languages that have adapted the Latin alphabet in at least one way, and give examples of the adaptations. What are the adaptations intended to accommodate?

If you practice a particular religion, what is the relationship between your faith and writing? Does your religion insist that texts be recorded in a particular language, or instead does it hope that holy works will be written in as many languages as

possible? Is the written word more or less important than the spoken word in your religious tradition?Describe the steps through which writing systems become phoneticized. What is interesting or surprising to you about this process?

In 2014, the Unicode Consortium announced that it would be releasing 250 new emoji characters. Emojis are essentially ideograms and pictographs. When texting with conventional orthography is so easy, why do you think emojis are so popular? What kinds of meanings do they convey? How are they used in conjunction with conventional text?

In what ways can religion's influence on language also be understood as political influence? What ethical issues are involved in the intertwining of religion and politics as far as language is concerned?

How has access to literacy been limited by social power relations? Can you think of additional examples from your own community? What personal, social, and political problems might the lack of access to literacy and lack of access to the Internet engender?

What do the Azerbaijani alphabet changes illustrate about the relationship between written language, national identity, religion, and politics? Were you aware of this relationship before now?

There have been numerous attempts to romanize Chinese logographic writing, including the creation of the successful pinyin phonetic system. What are the advantages and disadvantages of continuing the logographic writing system for Chinese languages, Chinese people, and the nation-state of China?