Languages In the World (24 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

- Blommaert, Jan (2008)

Grassroots Literacy: Writing, Identity, and Voice in Central Africa

. New York: Routledge. - Jensen, Hans (1969)

Sign, Symbol, and Script: An Account of Man's Efforts to Write

. New York: Putnam. - Kellner-Heinkele, Barbara and Jacob M. Landau (2012)

Language Politics in Contemporary Central Asia: National and Ethnic Identity and the Soviet Legacy

. London: I.B. Taurus. - Mueller, Pam A. and Daniel M. Oppenheimer (2014) The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking.

Psychological Science

25: 1159â1168. - Versteegh, Kees (1984)

Pidginization and Creolization: The Case of Arabnic

. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Versteegh, Kees (1997)

The Arabic Language

. New York: Columbia University Press.

Language Planning and Language Law

Shaping the Right to Speak

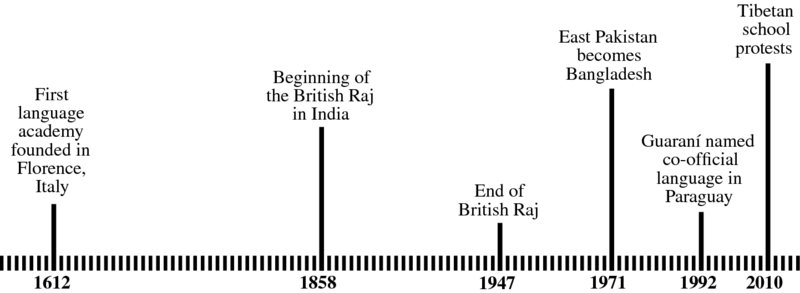

In 2010, government officials in Quinhai Province in western China detained 20 people for participating in protests that consumed the region for several days. The detained were not professional activists, radicals, or members of a well-funded political organization. They were students, some in middle school, some in high school, and others in college. They had joined thousands of other demonstrators, mostly other students in the Autonomous Region of Tibet. They were protesting a decision by the central government to change the medium of instruction in schools in the Chinese-controlled Tibetan-speaking regions from Tibetan to Putonghua, the standardized variety of Mandarin Chinese promoted by the central government in Beijing. Under the proposed policy, the Tibetan language could only be used in Tibetan-language class. As a form of protest, some of the students chanted “Equality of People, Freedom of Language.” Their prospects for equality and freedom have not improved. In

2015, the possibility that a Tibetan child will be educated in Tibetan through the course of his/her education are even bleaker than in 2010. The central government has continued its monitoring and crackdown on Tibetan schools.

Quinhai Province was once a part of eastern Tibet called Amdo. In 1928, China absorbed it and renamed it. In 1935, a baby was born in the town of Taktser in Quinhai/Amdo who would soon be identified as the fourteenth Dalai Lama. The intertwined relationship of language with religion and politics outlined in the previous chapter is at work in Tibet (see

Map 6.1

). A popular belief among Tibetans is that the 13th Dalai Lama chose to be reborn in historic Amdo in order for the people of that region to have a closer feeling to Tibet, as a way to reclaim Amdo as part of Tibet. We offer no opinion here on reincarnation; however, we can affirm that when a language ceases to be a medium of instruction and becomes an object of instruction, its days as a living language are numbered. The breath of the Chinese dragon (Mandarin) has been blowing ever closer to the remote, snow-capped Tibetan language for the last 3000 years, and now the dragon is breathing fire down the neck of the Tibetan language. The Tibetans revere their language, their script, and their scripture, and fear the impending loss of all three. As the Tibetan lama, Arjia Rinpoche (2010:vii),

1

puts it, Tibet's “language, its religion, its culture, and its native people are disappearing faster than its glacial ice.”

Map 6.1

Map of Tibet and China.

On the one hand, China protects minority languages in its constitution by allowing the Autonomous Regions, such as Tibet, to set language policy. On the other hand, China is pestered by the ideology of the monolingual nation-state discussed in Chapter 4. However, China is hardly alone in trying to square the circle of its multilingual reality, since societal multilingualism is the norm the world over. In fact, of the world's current 10 most populous nations â in descending order, China, India, United States, Indonesia, Brazil, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Russia, and Japan â only Japan could be thought of as solidly monolingual by the numbers. However, as discussed in Chapter 4, the presence of indigenous languages such as Okinawan and Ainu trouble Japan's purported monolingualism, to say nothing of English, Korean, and Chinese, which are also highly influential.

We now turn our attention to the ways that nation-states, once constructed, bring language planning and language law to bear on the language behavior of their citizenry in the halls of government, in classrooms, and sometimes even in the streets and marketplaces. None of the regulation and planning of language by the state can be carried forth without a well-developed bureaucracy and the resources of an ample and controlled print culture.

The crystallization of the one nation, one language ideology was a long time in the making and was supported by prior efforts to regulate language in the newly forming countries in Western Europe as they emerged from the Renaissance. The first language academy was the Italian

Accademia della Crusca

(The Academy of Bran) founded in 1582 by a group of intellectuals, and it is still in operation today. The emblem of the academy is a sieve, the idea being that the academy's job is to separate the wheat from the chaff. The academy is located outside of Florence, which means that the so-called chaff would be the features of Italian â pronunciations, words, and/or grammatical structures â not found in the Tuscan variety of Florentine speech. Clearly, the original purpose of this academy â and of many academies â was purism: the cleansing of anything not deemed good and proper Italian. Their next job was to create Standard Italian, and one of the ways they did so was to produce a prescriptive dictionary,

Vocabolario della lingua italiana

, in 1612.

Other European language academies followed Italy's example. The French Academy was established in Paris in 1635. The Spanish Academy was founded in Madrid in 1713. The Scientific Academic of Lisbon was created in Portugal in 1779. The Russian Academy, founded by Catherine the Great on the model of the French Academy, came along in 1783 (and was reconfigured in the Soviet era in 1944). At first, these academies, like the Italian model, were devoted to making, say,

Ãle de la Cité

French or Castilian Spanish pure of the perceived taint of surrounding varieties or they were interested in compiling the language and/or getting a sense of a unified whole. The Russian Academy, for instance, produced a six-volume Russian dictionary. However, over time and with the threat of globalization, the French Academy, in particular, turned its focus on sanitizing French of the English borrowings flooding into the

language. One high-profile example is the word

email

for which the Academy offered the properly French

courriel

. This does not mean, of course, that all French speakers use it, but surely they have heard it. As for the Spanish Academy, its mission has shifted to one of keeping the Spanish world linguistically intact, and it currently has affiliates with language academies in 21 other Hispanophone countries, including the United States, whose

Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española

was founded in 1973.

2

Notably absent from the very long international list of national language academies are entries for Anglophone countries such as Australia, Great Britain, and the United States. After Italy and France had established their academies, and Spain was founding hers, discussion took place in Great Britain about the need for such a language-planning body. In 1712, Jonathan Swift published his

Proposal for Correcting, Improving and Ascertaining the English Tongue

. By 1750, the proposal for an academy was dead, with the great lexicographer Samuel Johnson railing against such prescriptive bodies as striking a blow to English liberty. Later in the century, on the other side of the English-speaking Atlantic, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams debated the issue. Adams was in favor of an academy whose main job, he argued, was to be the regularizing of English spelling. The purpose of that effort was to create a reasonably spelled language for export, since the Founding Fathers were clear both in their mission to promote democracy on the world stage as the best form of government and in their idea that the English language was the best vehicle to carry this democracy around the world. Jefferson countered that it was not the government's business to regulate the speech of its citizens. He believed that each person had the right to speak in accordance with whatever group's speaking norms the citizen wanted. Jefferson's arguments carried the day.

Many academies understand their main purpose to be spelling reform, such as Adams envisioned for American English, and they may also set educational standards. A common undertaking involves increasing a language's lexical stock through neologism or borrowing, or through altering the meanings of existing words. In the twentieth century, the following academies, among many others worldwide, were established: in 1918, the Basques created the Group Keepers of the Basque Language as a bulwark against the surrounding languages; the Language Commission in Turkey was established in 1928 and did much more than simply switch from Arabic script to Latin script. In Atatürk's desire to make Turkey a modern state, he charged the Commission with purging Turkish of its Arabic loans â some of great antiquity, on the order of the presence of French borrowings in English â and had them replaced with native coinages; the Academy of the Arabic Language came into being in 1934 and united 10 Arabic-speaking countries. It is concerned with preserving Classical Arabic as well as with developing scientific and technical terminology; the Azerbaijan National Academy of Science was created in 1945 and was conveniently on hand when, after 1991, the Azerbaijanis faced another alphabet decision; the Academy of the Hebrew Language came about in 1953 and coined new words. Biblical Hebrew, which formed the basis for the modern language revival and which had not been spoken for nearly 2000 years at the time of the revival, was not fully up to the task of working in the modern world; finally, the People's Republic of China's State Language and Letters Committee was started under Mao Tse-tung in 1954 for the purpose of creating

simplified characters to improve literacy rates. The Polish Language Council is one of the more newly formed bodies, having been established in 1996.

The force of these academies is ultimately limited because speakers will for the most part speak the way they want to speak. Although academies tend to have only the power of suggestion, they can nevertheless create what we, the authors, think of as mischief. Languages are sociohistorical products. As such, a given ethnogroup's traditions, which contribute to the identity of the group, are built up over long periods of time and layered into their language. When an academy cuts people off from their history, linguistic and otherwise, it is always traumatic. It is also traumatic when an academy operates with a zero-sum attitude and the intent to erase what they perceive as the competition. A standard language is a good and even necessary thing for an ethnogroup/nation/world to have. However, it is not the only linguistic thing to have, and nonstandard varieties as well as different languages are sure to enrich the places and cultures in which they are spoken.

A bossy older sister smugly corrects her younger brother, “Everybody knows you're supposed to say

brought

not

bringed

, Nathan.” The press skewers President George W. Bush for saying in a speech that “some have misunderestimated the compassion of the United States,” and Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin is mercilessly mocked when the word

refudiate

slips out of her mouth. People prefer not to be corrected and mocked. In midseventeenth-century France, provincial nobles consulted language guides in order to avoid ridicule when they went to Versailles. These were not prescriptive grammars as such. Rather the royal courtiers themselves were aware of some of the distinguishing features of their language and leveraged them as marks of status. One scholar, Claude Favre de Vaugelas,

3

was alert enough to collect the courtiers' usages and to sell them to the rustics who were going to sit as close as they could to the cool kids' lunch table at court. In other words, prescriptivism comes in many forms and has likely always been a semiconscious and sometimes even conscious fact of life, with or without language academies, proper usage books, and language laws. This is true in societies in which asymmetrical power relations among social groups are reflected in sociolinguistic terms. In contrast, prescriptivism simply does not exist in small tribal communities where there is instead only the notion of “how we talk.”

Conscious prescriptivism in Western Europe was a slow development in the centuries leading up to the eighteenth century. As linguistic historiographer Douglas Kibbee so pithily put it, “The French have always been poster children for linguistic prescriptivism” (2011:1). So we will take France as our example and look first to law. Language and law have a long and intertwined history, and what unites them is the concept of

usage

. Just as the legal practices of a community over time produce common law (the usages out of which formal law is codified), so the linguistic practices of a community over time produce common vocabulary, phrases, and structures (the usages out of which prescriptive grammar is codified). Changes in legal practice in France over the centuries effected changes in linguistic practice. The significant event

was the eventual successful attempt by French kings to replace trial by ordeal with trial by inquest. In trial by ordeal, God determines who is right. In trial by inquest, the court takes accounts of two witnesses and necessarily needs a common language in order to compare them. The king's usage was law, and thus is a legal standard born.

Turning to language matters in England, although the English rejected the establishment of a language academy, they were not averse to establishing language standards. The prescriptive grammarians mentioned in Chapter 3 set themselves the task of what they called

ascertainment

: their job, given the various pronunciations and grammatical structures in eighteenth-century England, was to determine the one and only correct pronunciation for a particular word and the one and only correct grammatical structure for a particular expression. Once determined, that is, ascertained, the standards were then supposed to be set for all time. However, the grammarians reckoned without the most basic fact of linguistic life: language is constantly catching up to the conditions in which speakers find themselves.

An effect of the grammarian's work on ascertainment was the development of the idea the English language could be good or bad. The search for the best English thus ensued. In 1700, the writer John Dryden determined Chaucer to be the high-water-mark of the purity of the English tongue. By midcentury, the idea of language purity was taken to mean that the language had declined in value. Lexicographer Samuel Johnson, who wrote a monumental English dictionary, was the first to include quotes from authorities concerning the usage of the word being defined. He chose writers from before the Restoration, namely 1660, whose language was supposedly pure and undefiled. The assessment that English had been defiled created the urgent need for grammarians to fix what had gone wrong and return English to an earlier, more pure state. Modern language attitudes were born, and as a result speakers were subjected to judgments about their adherence to, or defection from, the new grammar rules.

An important belief to emerge from this period was the notion that the best English was spoken by the Queen. In 1712, writer/grammarian Jonathan Swift chose the reign of Queen Elizabeth as the time when the English language received its most improvement. Since Swift's time, the phrase

the Queen's English

has remained popular. The question can now be asked: Does the Queen of England speak the Queen's English? In a study of Queen Elizabeth II and her yearly Christmas message broadcast by the BBC since 1952, Harrington et al. (2000:927â928) found that the Queen's vowels had drifted over the decades from the standard accent known as

received pronunciation

to a southern British accent more typically associated with speakers who are younger and lower in the social hierarchy. It has long been known that the younger generation drives changes in pronunciation. The question behind the study of the Queen's English was to determine to what extent older members adapt to the changes around them. The answer is: older members are as enmeshed as everyone else in the dynamics of the language loop.

Language creates, and is created by, human bonds that lasso us in and keep us within the human circle. In this particular context of prescriptivism, one of the many distinguishing features of the language loop stands out: its unavoidability. You can (and perhaps should) avoid talking about certain topics with business associates and in-laws; religion and politics come to mind. However, when talking about whatever topic, you cannot avoid the use of one variety of speech or another, which also necessarily

privileges one variety over another. We, the authors, are aware that we participate at all times in the unavoidability of language. For instance, we have written this book in Standard American English, and the Queen of England herself does not escape the semiprescriptive dynamics of the language loop. After all, she is only human.

Because our primary interest in this book is not on the microdynamics of individual and face-to-face interactions, we turn our attention toward the macrodynamics of social and political language planning and control, which are explicit forms of language control exercised by nation-states. We note that those responsible for language planning are rarely linguists or language experts and almost always politicians or government officials. Of course, these individuals, acting on behalf of a state, likely believe their language-planning efforts are for the good of the majority. This is surely the case in China, where state language planners see the promotion of Putonghua in regions such as Tibet as a means of recruiting minority populations into China's developing economy, which is overwhelmingly oriented around this official version of Mandarin. In 2013, the state announced that 400 million Chinese citizens could not speak Putonghua and identified this inability as a stumbling block for the country's economic advancement. In contrast, many Tibetans see the legal imposition of Putonghua into Tibetan regions of China as a form of cultural imperialism and even religious intolerance, given the important role of the Tibetan language in Buddhist culture.