Languages In the World (35 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

- Elbert, Samuel and Mary Kwwena Pukui (1979)

Hawaiian Grammar

. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Colonial Consequences

Language Stocks and Families Remapped

Visitors to Vietnam, if they go to the mountain town of Da Lat or the beach town on Con Dao Island, might be surprised to see what looks to be a smaller version of the Eiffel Tower sprouting from the top of a building in the city center. Upon closer inspection, visitors might decide that they are indeed looking at an Eiffel Tower. They might figure that it functions as an antenna, but they might also wonder why this distinctive shape came to be on the roof of the post office. The answer is that at the end of the nineteenth century, the French created the postal system in Vietnam when it was part of the French colonial empire called

Indochine

. By the way, the main post office in Ho Chi Minh City (Sai Gon), which sports a normal-looking antenna, was designed and built by Gustave Eiffel himself. Pertinently, the Vietnamese word for

âpost office' is

bÆ°u Äiá»n

:

bÆ°u

is from the French word

bureau

âoffice,' and

Äiá»n

is the Vietnamese word for âelectricity.'

The French took an interest not only in the buildings they themselves built but also in those they encountered in this part of the world. The most spectacular are the temple complexes at Angkor, located in present-day Cambodia. Angkor was the ancient capital of the Khmer Empire, founded in the ninth century and abandoned in the fifteenth century to the will of the jungle. The first European to see the city was the Catholic Father Bouillevaux, who happened upon these exotic and overgrown structures in 1850. A decade later, French naturalist and explorer, Henri Mouhot, touted to the European press the beauty of this location, and Western efforts to restore the site began. The most mysterious and magical of all the temples is Ta Prohm, a veritable ruin where the sinuous roots of kapok trees, some thicker than a large man's thigh, snake around and through the temple walls. In 2001, British film director, Simon West, chose this visually startling location for the scene in

Lara Croft: Tomb Raider

where Lara encounters a mysterious girl who tells Lara where to go next. Given the partial colonization of the imagination exerted by the global movie industry, tourists today are willing to stand in line for hours on end at a particular wall in Ta Prohm in order to have their picture taken in front of this famous movie set.

The power dynamics of concern in Part II are clearly at work here in Part III. The successful expansions described in Chapter 7 involved the power of the innovation of farming, the possession of the most advanced technologies like ploughs and harnesses, the domestication of goats and yaks and horses, and the invention of conveyances such as a cart or a sled. Today, the expansive power of a culture might be the blockbuster movie. In this chapter, we foreground the movements impelled by power in the ways that certain organized political structures feel the need to expand their territory. We call these movements

colonization

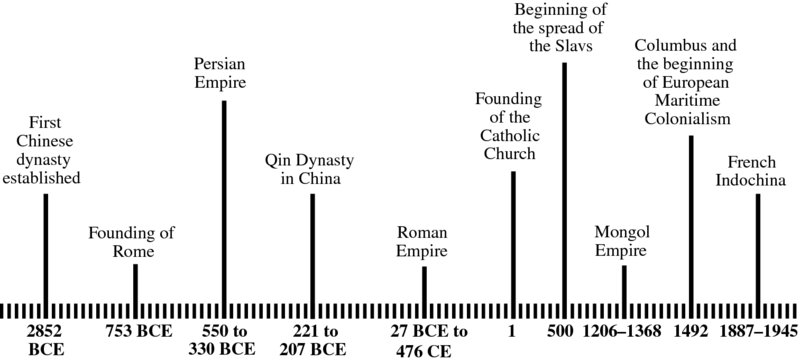

. We begin with a look at the major pre-Columbian colonizers: the Chinese, the Persians, the Mongols, and the Slavs, as well as the Romans. We move on to examine the linguistic effects of another type of colonization â that which has occurred through the spread of world religions. In our review of Making Language Official in Chapter 6, we mentioned the end of post-Columbian European colonialism carried out by the British, Spanish, Dutch, French, Germans, Italians, and Portuguese, and so we do not need to review its beginnings in the present chapter. Instead, we end by taking a look at a different kind of linguistic legacy of colonialism, namely the way a variety of English has come into being in the particular eco-linguistic environment of Singapore.

In the previous chapter, we called the spreading out of a people from a homeland an

expansion

, and it is the case that many of those expansions were into already-inhabited territories. In this chapter, we explore the linguistic effects of colonialism. The word

colony

is from the Latin

colonia

âa place for agriculture, farm, settled land.' We distinguish

expansion

from

colonialism

by defining the latter in terms of movement away from an existing established state, such as Rome, which over time acquired colonies and became an empire. We reserve the term

migration

to refer to human movements

when a political border is crossed. Migrants can cross international boundaries, but they can also cross intranational boundaries, for instance when someone in the United States takes a job in another state. In ordinary speech, it is perfectly acceptable to say, for instance, that what we are calling Globalization 1.0 is a kind of first colonization of the world, and anthropologists have no hesitation saying that humans have been migrating all over the planet for a very long time. We do not insist that our terms be used in our ways outside of this book. We make the distinctions between the terms

expansion

,

colonization

, and

migration

here only to keep our differing time-depths straight.

Colonialism can occur by settlement, when large numbers of colonizers enter a territory and take it over en masse, or by administration, when fewer colonizers enter an area and then rule it for exploitive purposes: to send valuable natural resources or raw materials to the capital and/or to cultivate the natural resources, for example, sugar, rubber, coffee, etc., on plantations for consumption in the capital and for profit on markets around the world. As colonizers move into a territory, whether as settlers or administrators, and stay for however long they remain, their languages inevitably affect the local languages.

Let us embroider for a moment on the terminological effects of colonization on Vietnamese. The French came first as proselytizers (religious converters) and later as political and economic administrators. The French presence in Vietnam began in the seventeenth century with French Jesuit missionaries, as you may recall from Chapter 5, who established

quá»c ngữ

, the transcription of Vietnamese into the Roman alphabet. In 1853, French explorers, doctors, and political administrators began to come largely in order to claim and then protect these potentially rich lands from the British and the Dutch who were already in Malay and Indonesia, respectively. In 1887, the existence of French Indochina as a political entity was established and included present-day Cambodia and Vietnam. It lasted until 1945.

The Vietnamese borrowing

bÆ°u

is suggestive of the fact that the French set up more than just post offices and in fact established an entire bureaucracy. The presence of French loanwords in modern-day Vietnamese is light yet discernible, and the borrowings represent domains of influence and of the new. There is

ga

from French

gare

âtrain station' and

ga ra

from French

garage

âgarage.' The bicycle was introduced, and now the Vietnamese have

xi clo

from French

cycle

âcycle,'

ghi Äông

from French

guidon

âhandlebar,' and

pê Äan

from French

pédale

âpedal.' There is also

vô lÄng

from French

volant

âsteering wheel.' A new type of building material is called

be tông

from French

béton

âconcrete.' A hint of French customs comes through in the half-calque/half-borrowing

tiá»n boa

meaning âtip (for a service),' where

tiá»n

is Vietnamese for âmoney,' and

boa

comes from French

boire

âto drink,' which is found in the compound

pourboire

âfor to drink' meaning âtip.' The French rulers have gone, but they left their footprint on the land in their buildings and their railroads and evidence of administrative and cultural effects sprinkled in the language. In Vietnam today, the colonial past is still present.

Before the arrival of the French, the Chinese dominated what is now Vietnam for a thousand years (111 BCE to 938 CE), and the effect of this domination on Vietnamese is massive and deep.

1

Entire portions of the Vietnamese vocabulary are borrowings from Chinese. The importance of Chinese on Vietnamese vocabulary is similar to that

of Greek and Latin on English vocabulary. We offer here only one example out of thousands. In English, the word âdentist' is from the Latin word for âtooth,' namely

dens

. In Vietnamese, the word for âdentist' is

nha s , which is a compound from Chinese borrowings

, which is a compound from Chinese borrowings

nha

âtooth' and

s âprofessional, person of highest learning.'

âprofessional, person of highest learning.'

2

(The Vietnamese word for âtooth' is

rÄng

.) The prestige of the Chinese portion of the Vietnamese vocabulary is so great that the Vietnamese people receive much etymological training throughout their school years, and they know which parts of the vocabulary are native Vietnamese and which are Chinese, in a way that English speakers do not know which part of their vocabulary is Germanic and which is French/Latin/Greek. While English speakers can put together a phrase such as

cordial greeting

with âcordial' from Latin and âgreeting' from Germanic, the Vietnamese speaker does not. For the phrase

beautiful person

, they will choose either a VietnameseâVietnamese combination

ngừơi Äẹp

or a ChineseâChinese combination

mỹ nhân

.

China has the longest continuous existence as a state, the longest policy of migratory colonialism, and the oldest continuous written records, some of which document those migrations. In the previous chapter, we noted that the homeland of the early Sino-Tibetans was in the valley of the Yellow River in the central plains of northern China. We noted their movements west, south, and east, with the differentiation of the population into the Tibeto-Burmans in the west and the Chinese in the south and east. When we speak of âthe Chinese,' we are speaking of the ethnic group called

Han

. They are so called in reference to the Han Dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE). This dynasty succeeded the Qin Dynasty (221â207 BCE), which brought a number of regions under its control and became the first imperial dynasty. The name

Han

may have been preferable for this ethnic group to

Qin

because the Qin Dynasty was so short-lived. The Han Dynasty is also considered something of a Golden Age in Chinese history. Of interest is the possibility that the name

Qin

may be the etymological root of the European word

China

, although the exact etymological origin is debated. The name

Middle Kingdom

(ZhÅngguó) for China refers to the original, central states in the Yellow River Valley. Beijing is not on the Yellow River, but it lies a bit north and west of where the Yellow River flows into the Pacific. The first Chinese dynasty dates as far back as 2852 BCE.

Records of government-encouraged migrations begin in the seventh century BCE, and the first ones were southward from the Wei River Valley to the lower Yangtze whose original inhabitants are identified by Chinese historians as the

bai yue

(the hundred Yue). By the third and second centuries BCE, the government records begin to include the numbers of people moved, with the first instance showing that almost two million people from the central plains moved further to the east and south, and all the way into northern Vietnam (

nam

means âsouth'). Once again, the people they encountered are recorded as being the

bai yue

. The largest migration of the early period was in the second to fourth centuries CE when three million people moved from the central plains south and east to the coast. There they met the Wu and Chu peoples, both Chinese. Almost every century from the beginning of recorded Chinese history bears witness to a government-encouraged migration. In recent times,

from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, for instance, tens of millions of people in provinces on the east coast around Beijing migrated northward to Siberia. There they met the non-Chinese Altai people. In the twentieth century people from all areas of China migrated into Inner Mongolia. And as we already saw at the beginning of Chapter 6, significant Mandarin incursions have recently taken place in the western Tibetan-speaking Quinhai Province and in the Tibetan Autonomous Region. Indeed, they have been doing so for thousands of years. A table of these impressive migrations can be found in LaPolla (2006:229).

3

The first thing to note is that when the Chinese migrated, they rarely moved into unoccupied territory. The second thing to note is that, given the large numbers of migrating people, the indigenous populations were greatly affected, and the arrivals of Han triggered secondary migrations of the people originally inhabiting the colonized area. If the indigenous people did not go elsewhere, they were absorbed. Like the Spanish policies during the conquest of the Americas mentioned in note 6 at the end of Chapter 2, there was purposeful mixing of peoples in the colonized areas with the aim of bringing them into the Han nationality. Not surprisingly, a genetic study of the population generally known as Han shows enough geographic variation in a particular coding region of mtDNA to prompt researchers to propose new haplogroups, making the Han a far-from-homogeneous ethnic group. This genetic study was furthermore able to provide evidence for speculating that the Proto-Han made an initial move from south to north in the Paleolithic era (moving toward their homeland, in our terms) and then, after they had settled, expanded, and colonized territories from north to south, as well as east to west (Yao et al. 2002). This genetic evidence lines up not only with the prehistoric information coming from linguistic reconstructions and archeology but also with the historical records kept by the Chinese government.

Most importantly, from our point of view, the resulting mixtures of people from these migrations explain many of the features found in the current Chinese varieties, which may be as few as seven and as many as 10 or more mutually unintelligible varieties, depending on how one counts. The aboriginal

bai yue

are an important part of the linguistic story in south and southeastern China. They are non-Han, and the qualifier âhundred' given to them by the Chinese historians suggests that those people covered by the term

yue

were of many ethnicities. Modern philologists often divide them into two groups: one that spoke Austro-Asiatic-related languages and another that spoke Tai and Hmong-Mien (known in Chinese as Miao-Yao)-related languages. In the more distant prehistoric period, the

bai yue

may have been speakers of a larger phylum, one that broke up over time and into stocks such as Hmong-Mien and putative Austric, which includes Austro-Asiatic, Austronesian, and Tai (see LaPolla 2006:233). Not surprisingly, the Chinese variety Cantonese, spoken in the south and well known in the West because it is spoken in Hong Kong, shows lexical borrowings from both Tai and Hmong-Mien. Only one syntactic construction in Cantonese will be mentioned here, namely the objectâdative construction, where the direct object precedes the indirect object and is exemplified by the phrase:

| ngo 5 | bei 2 | cin 2 | keoi 5 |

| âI' | âgive' | âmoney' | â(to) him.' |

Mandarin and most other Chinese varieties have the word order âI give him money.' The preferred Cantonese word order can be found in both Tai and Mien languages. It is considered an areal feature (Matthews 2007:223â224). In Chapter 11, we will take up some of the linguistic consequences of these government-encouraged migrations.

Although very large in area, China is also relatively self-contained, with the Pacific Ocean to the east and mountains to the west. It has also been inhabited for a very long time, meaning that there has also been a long time for an organized government to form and to have been in control of the territory, as we have just seen. The other empires we want to outline in this chapter distinguish themselves from the Chinese situation in two ways. First, they are more recent, relatively speaking. Second, particular geographic conditions come into play in their expansions, and we now turn to an examination of those conditions.