Languages In the World (30 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

We said in the introduction to this chapter that the small set of cognate words for the supreme deity offered a start to reconstructing Proto-Austronesian, beginning with a set of cognates in the Polynesian branch. To remind you what was said in Chapter 3, the reconstructive process starts by establishing sound correspondences, and the

names for this god â Tagaloa, Tangaloa, Tangaroa, Ta'aroa, and Kanaloa â offer four promising possibilities:

- the first syllables have the initial consonant alternations:

- #t â¼ #t â¼ #t â¼ #t â¼#k;

- #t â¼ #t â¼ #t â¼ #t â¼#k;

- the second syllables have the consonant cluster alternations:

- -g- â¼ -ng- â¼ -ng- â¼ Ê â¼ -n-;

- -g- â¼ -ng- â¼ -ng- â¼ Ê â¼ -n-;

- the third syllables have the consonant alternations:

- -l- â¼ -l- â¼ -r- â¼ -r- â¼ -l-; and

- -l- â¼ -l- â¼ -r- â¼ -r- â¼ -l-; and

- the vowels are stable.

Why would comparative philologists find the alternations in this small set of cognates so promising? The answer is because they apply a version of the uniformitarian hypothesis to the reconstructive enterprise, which is a way of saying that once philologists have a sense of the types of phonetic processes at work in one or more language families, they are reassured when they see the same (or similar enough) processes at work in other data sets. To remind you again what was said in Chapter 3, a typological classification captures similarities among languages regardless of their historical and geographic connection. Typological classifications give linguists information about the kinds of things speakers do with their languages as they physically disperse, and their languages develop along different trajectories. Typological information thus sometimes functions as a plausibility check.

Let us take a look at the Polynesian data set, phonetic segment by phonetic segment:

- the initial consonants [t] and [k] belong to a

natural class

of sounds because they share the phonetic features [+stop] and [-voice]. They differ only in their place of articulation, [t] being [+dental] and [k] being [+velar], so the possibility of their correspondence is easy to imagine; - it is also easy to reconstruct

*

-ng- for the second syllable, and then posit that Samoan regularly lost the

*

-n-, and Hawaiian regularly lost the

*

-g-, while Tahitian turned the cluster into [Ê] a glottal stop; - alternations of [l] and [r] are widespread in families of languages that have one or the other or both phonemes, and so this alternation raises no eyebrows, for example, the French and Spanish cognates for âpurse'

bourse

and

bolsa

, respectively; and - the stable vowels in word final position can be considered a gift to the philologist.

The tentative reconstruction for the name of the god would thus be something like

*

tangaLoa, where the L signals a midpoint between an [l] and an [r] whose resolution would depend on further information.

As a note of caution, we have said that religion can be a compelling cultural influence, and so it is possible that one or the other of these cultures may have borrowed the religious beliefs, along with the name for the god, and adapted the pronunciation into the sound system of their language. So, the next task for comparative philologists is to find as many sets of cognates showing these correspondences as possible.

The question arises: Is there any evidence of regular sound correspondences across the Polynesian languages and the thousands of miles of water? The answer is: Yes.

For instance, in Samoan, Tongan, MÄori, Tahitian, and Hawaiian, the cognate set for âone' confirms the initial consonant [t] â¼ [k] correspondence:

t

asi â¼

t

aha â¼

t

ahi â¼

t

ahi â¼

k

ahi

The cognate set for âperson' shows that the consonant correspondence is not restricted to initial position but is found throughout the word, as the third syllables demonstrate:

taga

t

a â¼ tanga

t

a â¼ tama

t

a â¼ taÊa

t

a â¼ kana

k

a

A quick check of a Hawaiian grammar, furthermore, shows that [t] is not in the phonetic inventory of this language. Thus, it is safe to say that all

*

[t] became [k] in Hawaiian. As for the consonants in the medial syllable of the MÄori word

tamata

âperson,' further investigation is needed to account for why there is an -m- instead of the expected -ng-. Furthermore, the cognate set for âone' shows another consonant alternation, namely -s- â¼ -h- â¼ -h- â¼ -h- â¼ -h-, along with some vocalic differences, which set the philologist down a new path of investigation. On the whole, however, with just these few examples, it looks like it is possible to imagine a Polynesian language family. However, in order to confirm the possibility, grammatical similarities also must be found. Upon investigation of the grammars of these languages, a Polynesian language family can be posited, and it furthermore looks possible to draw a line to attach it to a larger Austronesian stock (

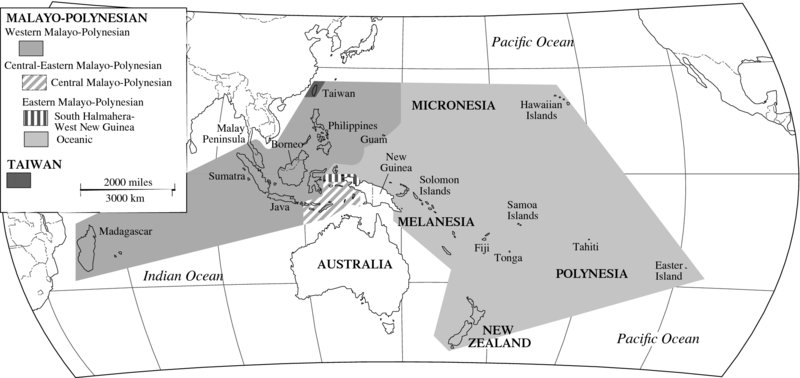

Map 7.1

).

Map 7.1

Austronesian languages.

The precise terminology here matters. We are using the term

family

to refer to a group of languages whose clear, historical relatedness has a time-depth of 2500â4000 years. We are using the term

stock

to refer to a group of languages whose (hopefully clear) historical relatedness has a time-depth of 5000â10,000 years. Of further importance is the fact that the techniques of reconstruction do not apply at a time-depth much greater than 10,000 years. To round out our temporal terminology, we use the term

phylum

to refer a group of languages with a possible relationship that dates back 15,000â40,000 years or more. Finally, the term

lineage

is used as a cover term for a language grouping of any age.

In Chapter 3, we introduced the idea of linguistic reconstruction. We can now boil the whole of the reconstructive enterprise down to one sentence: it is based on one fact, one hypothesis, and one principle. The fact is that massive lexical and grammatical similarities hold among certain groups of languages. The hypothesis is that these similarities must have descended from a common source. The principle is that of the regularity of sound change. Another way of stating this principle is to turn it around and to say that a shared irregularity is the mark of common descent. All Germanic languages share the so-called irregularity of having #f- where Latin and Greek have #p-. Thus, the Germanic languages make their own branch. The PIE word for ârain' can

be reconstructed as

*

plewõ and shows up, for instance, in Latin as

pluor

ârain.'

9

The Proto-Altaic word for ârain' can be reconstructed as

*

agà . The languages that descend from these two protolanguages will share the irregularity of those original forms. The difference between

*

plewõ and

*

agà is not usually called an irregularity. Rather, the difference is attributed to the arbitrariness of the sign. Since the word for ârain' could be anything, those languages having a similar phonetic form for this thing/concept are likely to have inherited it, and the languages that share some form of

*

plewõ are therefore likely to be related, just as those that share some form of

*

agà are likely to be related. Arbitrariness can be called

the original irregularity

. The dramatic difference between

*

plewõ and

*

agà is one of the multitude of differences that distinguishes the Indo-European languages from the Altaic languages.

The moment the philologist begins the reconstructive effort, however, intriguing problems immediately arise to trouble the fine principle of the regularity of sound change and its inverse of shared irregularity marking common descent. These are described in the following subsections.

Philologists need to know where to look in the vocabularies and structures of the languages in order to begin the reconstructive process. They want highly stable words and constructions presumably inherited from an imagined protolanguage, not words and constructions borrowed through contact with speakers of languages from a different family. Likely categories of stable vocabulary include the names for: family members and relationships, body parts, features of the natural world (sun, moon, sky, etc.), numbers one through 10 at least, and common animals and plants indigenous to the homeland.

Likely categories of stable structural features include:

- The sound system and syllable structures: in Chapter 5, we noted that the Greeks needed to turn some of the Phoenician symbols into vowels because Indo-European languages characteristically have syllables with a large number of consonant clusters. They also have midsized phonemic inventories. By way of contrast, Austronesian languages avoid consonant clusters and have relatively small phonemic inventories.

- The pronoun system and what kinds of distinctions are made: singular, dual, plural, etc., as well as the words for the pronouns themselves. Hawaiian, for instance, has we-inclusive

kakou

âall of us including you' and we-exclusive

makou

âall of us excluding you,' and this distinction seems to have been a feature of Proto-Austronesian, since it is found throughout the Austronesian-speaking world from Hawaiian in the east to Malagasy in the west and important points in between, including Indonesian and Tagalog. - Word-formation preferences: Swahili favors agglutinative morphology by prefixing, while Turkish favors agglutinate morphology by suffixing, as mentioned in Chapter 3. A widespread characteristic of Austronesian languages is their use of infixing, which involves inserting a personal pronoun morpheme and/or a tense morpheme into the word itself. Tagalog has borrowed the English word

graduate

. To say the past tense âI graduated,' the infix

-um-

is inserted near the beginning of the word

gr

um

aduate

. - Word-order patterns: many, but not all, Austronesian languages have verb-initial word order. Language stocks and families tend to have preferred word orders, but one of the many structural features that can change over time in a language is dominant word order. Nevertheless, widespread preferences for word order in a family and stock are common. The Dravidian languages, for instance, all tend to be SOV. It is not surprising that Austronesian languages all show a preferred VSO order.

Instabilities in some of these more-or-less stable categories can always be found. Although pronouns are not likely candidates for replacement, speakers of English gave up their West Germanic third person pronouns along with the plural forms for the verb âto be,' and they borrowed

they

,

them

,

their,

and

are

from Old Norse. Numbers can be revealing. When a language has two ways to refer to numbers, this is often a sign of long domination by another language. The English ordinal

second

is not based on the English cardinal

two

but is borrowed from French. The Vietnamese numbers begin:

má»t

,

hai

,

ba

,

bá»n

â¦Â , and the days of the week begin:

thứ hai

meaning âday two,' namely Monday, and

thứ ba

meaning âday three,' namely Tuesday. However, the word for Wednesday is

thứ tư

meaning âday four' (instead of

thÆ° bá»n

), after which the names for the days of the week revert to compounds with the Vietnamese cardinal numbers. Additionally, in Vietnamese the word for an intersection of two streets is

ngã tư

, meaning âcrossroads/corners four.' The word

tÆ°

âfour' is a Chinese borrowing.

Apart from these minor observations, we can say that the

borrowing

patterns we see today are probably those that have existed for all time, and when we eliminate those, we get down to the stable vocabulary. In English, we easily spot borrowings in categories such as food (

sushi

,

taco

,

wurst

), clothing (

kimono

,

serape

,

dirndl

) and specialized domains such as opera, which gives us Italian words such as

soprano

,

alto

,

vibrato

, and so forth, along with the word

opera

itself.

The Old English plural of âcow' was

kine

. The Modern English plural is

cows

. No plausible regular sound change can be invented to account for this change. Only from the reformation of the noun classes during the Middle English period, when the -s# plural that was on 35% of Old English nouns began to generalize, can the change from

kine

to

cows

be explained. The plural

cow

s was reformed by analogy to the many other nouns adopting the -

s

plural at that time. Analogy can also be called

pressure of the system

. When children learning English say “she bringed me a cookie,” they are forming the past tense by analogy to the many other past tenses they know that form a system. Eventually they adjust to the normative and irregular form

brought

.

The example of

bringedâbrought

demonstrates how the principle of shared irregularity as a mark of common descent and the workings of analogy lock into one another. In Modern German, âto bring' is

bringen

, and the past tense âI brought' is

ich brachte

. In Modern German, âto think' is

denken

, and the past tense âI thought' is

ich dachte

. Despite the fact that English and German have verbs like

ringârangârung

/

ringenârangâgerungen

and

drinkâdrankâdrunk/trinkenâtrankâgetrunken

, the

verbs âto bring' and âto think' in both languages share closely related irregular past tenses. They must have inherited these irregularities rather than independently inventing them in just those words. This shared irregularity is thus (one of) the mark(s) of the common descent of English and German as West Germanic languages. At the same time, the philologist has to be on the lookout for forms that speakers have analogized, that is, regularized over time, and be willing to invoke the working of analogy to override the principle of the regularity of sound change. The principle of shared irregularity marking common descent and the working of analogy help the philologist understand the contours of the jigsaw puzzle pieces used to reconstruct the protolanguage.

The reconstructed PIE word for âdaughter-in-law'

*

snusós

makes an interesting example.

10

The

-ós

is of interest because it is a masculine ending reconstructed for a clearly feminine entity. The reason for the choice of the ending comes from the forms for the attested words in Latin

nurus

and Greek

nuos

, which both have masculine endings. All other Indo-European cognates have a feminine ending. So, Greek and Latin must have inherited the shared irregularity of a feminine entity carrying a masculine ending. All other languages must have analogized the ending to make it conform to other feminine nouns, because there is no sound change that will account for why the other languages changed an -os# to an -a#. This reasoning makes more sense than imagining that Greek and Latin inherited an originally feminine ending and both independently and for no apparent reason decided to give it a masculine ending.

Long before there were language academies and language police, societies as a whole placed restrictions on words. Today, the words for certain body parts and body functions tend to come under taboo, as well as do so-called four-letter words. No sound laws will account for the phonetic shape of the nearly endless string of euphemisms in English for words under taboo:

dang

,

darn

,

durnit

,

fooey

,

fudge

,

gee

,

gee whiz

,

gee willikers

,

golly

,

gosh

,

heck

,

jeez

,

sam hill

,

shoot

,

shucks

, â¦Â the list is long. The only way to account for how they sound is by how well they deform the word under taboo, thereby diminishing its strength, while still keeping some part of it audible.

The names for things to be feared and respected also need to be altered, so that one does not draw the power and the wrath of the thing named. (Don't take the Lord's name in vain!) Medical researchers may refer to cancer as The Big C. The M-word is uttered at a confirmed bachelor's peril. The L-word has a variety of interpretations. Sometimes, whole words are replaced. In modern Judaism, the word

Adonai

refers to the Lord because the name

Yahweh

is not to be pronounced. Some times, the words are not uttered in the first place. “I'm hoping for a good outcome for my grant application, but I don't want to tell you to which funding agency I submitted it, so as not to jinx it.” We don't really and truly believe in the magical power of words (do we?), but sometimes we behave as if we do.

The Germanic, Baltic, and Slavic branches of Indo-European presented philologists with a puzzle concerning the question of whether or not the Proto-Indo-Europeans knew about bears. It seemed that they lived in an area that had bears, and enough IE branches had words for bears that made the reconstruction

*

arkth- possible for âbear.' However, the northern tribes â the ones presumably encountering bears fairly

regularly â had words for this animal such that no amount of sound correspondences could lead back to

*

arkth

-. The problem was resolved by appealing to the notion of taboo replacement. Each language found a way to refer to bears without invoking them, and they did this by nicknames. The Germanic peoples called them some form of âbruins,' that is, a âbrown one,' making

bear

and

brown

cognates. The Baltic people referred to them as a âshaggy one,'

lÄcis

, while the Russians called them a âhoney-eater,'

medved

, which is also a Russian family name. The Bear itself is the symbol of Russia.

We have spoken of population genetics and linguistic reconstruction, but thus far we have conjured without the help of cultural anthropology or archeology. Part of the interest of philology is that reconstructed languages give glimpses into the cultural and intellectual conditions of the speakers in a way that the archeological evidence provided by burial mounds or pottery shards cannot. What words can and cannot be reconstructed for a protolanguage reveal much about the local conditions in which the speakers of that language lived, the material culture they possessed, and even some of the abstract and/or religious and political ideas they held. At the same time, cultural information can and at times must be imported into the reconstructive enterprise. Albanian

nu

means âbride.' It was used to help reconstruct PIE

*

snusós

, despite its phonetic divergence from the original form, because there is ample evidence that Indo-European culture was highly patriarchal, and a bride would leave her family home and move in with the husband's family, thus becoming at the same time a daughter-in-law. Thus,

nu

is deemed an appropriate cognate. For certain Native American reconstructions, the words for âhair' and âfeather' might be legitimate cognates.

Philologists bring long-lost human worlds into existence by organizing available facts by means of tested principles and feats of logic. Historical and comparative philology is a sometimes frustrating, often challenging, and always fascinating exercise in ingenious inference.

Some of this ingenuity is mobilized for the purposes of determining the historical homelands of the speakers of the various protolanguages. Archeologists have long worked in tandem with cultural anthropologists and linguists, and more recently with population geneticists to determine the most likely locations for these homelands. It is generally agreed that Formosa/Taiwan was the incubator for Proto-Austronesian. However, in the case of the homeland of the pre-Proto-Austronesians, the possibility of their settlement around Hangzhou Bay before arriving in Formosa/Taiwan is cast in some doubt by the cultural fact that in this area of China, the agricultural staple is rice, while the Formosan's is millet, and the Formosan culture has an agricultural rite the heart of which is millet. On the other hand, a word for ârice' can be reconstructed for Proto-Austronesian. Lining up what can be imagined for the past with what is known in the present is a tricky business.