Languages In the World (52 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

- Andrews, Edna (2012) Markedness. In Robert I. Binnick (ed.),

Tense and Aspect

. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 212â236. - Balter, Michael (2013a) Ancient DNA links Native Americans with Europe.

Science

342: 409â410. - Balter, Michael (2013b) Farming's tangled European roots.

Science

342: 181â182. - Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi (2000)

Genes, Peoples, and Languages

. New York: North Point Press. - Chebanne, Andy (2010) The Khoisan in Botswana: Can multicultural discourses redeem them?

Journal of Multicultural Discourses

5: 87â105. - Cysouw, Michael and Bernard Comrie (2013) Some observations on typological features of hunter-gatherer languages. In Balthasar Bickel, Lenore A. Grenoble, David A. Peterson, and Alan Timberlake (eds.),

Language Typology and Historical Contingency: In Honor of Johanna Nichols

. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 383â394. - Darwin, Charles (1968 [1859])

The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, Edited and with an Introduction by J.W. Burrow

. London: Penguin Books. - Dediu, Dan and D. Robert Ladd (2007) Linguistic tone is related to the population frequency of the adaptive haplogroups of two brain size genes, ASPM and Microcephalin.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

104.26: 10944â10949. - Dixon, Robert M.W. (1994)

Ergativity

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - Evans, Patrick D., Sandra L. Gilbert, Nitzan Mekel-Bobrov, Eric J. Vallender, Jeffrey R. Anderson, Leila M. Vaez-Azizi, Sarah A. Tishkoff, Richard R. Hudson, and Bruce T. Lahn (2005) Microcephalin, a gene regulating brain size, continues to evolve adaptively in humans.

Science

309: 1717â1720. - Gil, David (2009) How much grammar does it take to sail a boat? In Geoffrey Sampson, David Gil, and Peter Trudgill (eds.),

Language Complexity as an Evolving Variable

. Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 19â33. - Kroeber, Theodora (1961)

Ishi in Two Worlds: A Biography of the Last Wild Indian in North America.

Berkeley: University of California Press. - Levinson, Stephen (2003)

Space in Language and Cognition: Explorations in Cognitive Diversity

. New York: Cambridge University Press. - Lieberman, Philip (2013) Synapses, language, and being human.

Science

342:944â945. - Maddieson, Ian (2011, September 24) Consonant inventories. In Matthew S. Dryer and Martin Haspelmath (eds.),

The World Atlas of Language Structures Online

. Retrieved from Max Planck Digital Library.

http://wals.info/chapter/1

. - McWhorter, John (2001) The world's simplest grammars are Creole grammars.

Linguistic Typology

5.2: 125â166. - Mekel-Bobrov, Nitzan, Sandra L. Gilbert, Patrick D. Evans, Eric J. Vallender, Jeffrey R. Anderson, Richard R. Hudson, Sarah A. Tishkoff, and Bruce T. Lahn (2005) Ongoing adaptive evolution of ASPM, a brain size determinant in

Homo sapiens

.

Science

309: 1720â1722. - Morris, Simon Conway (2011) Complexity: The ultimate frontier.

EMBO Reports

12: 481â482. - Nichols, Johanna (1986) Head-marking and dependent-marking grammar.

Language

62.1: 56â119. - Nichols, Johanna (1992)

Linguistic Diversity in Space and Time

. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. - Nichols, Johanna (2010) Macrofamilies, macroareas, and contact. In Raymond Hickey (ed.),

The Handbook of Language Contact

. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 359â375. - Pereltsvaig, Asya (2012)

Languages of the World: An Introduction

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - Rootsi, Siiri, Lev A. Zhivotovsky, Marian Baldovic Caron, Manfred Kayser, Ildus A Kutuev, Rita Khusainova, Marina A. Bermisheva, Marina Gubina, Sardana A. Fedorova, Anne-Mai Ilumäe, Elza K. Khusnutdinova, Mikhail I. Voevoda, Ludmila P. Osipova, Mark Stoneking, Alice A. Lin, Vladimir Ferak, Jüri Parik, Toomas Kivisild, Peter A. Underhill, and Richard Villems (2007) A counter-clockwise northern route of the Y-chromosome haplogroup N from Southeast Asia towards Europe.

European Journal of Human Genetics

15: 204â211. - Tishkoff, Sarah, Mary Katherine Gonder, Brenna M. Henn, Holly Mortensen, Alec Knight, Christopher Gignoux, Neil Fernandopulle, Godfrey Lema, Thomas B. Nyambo, Uma Ramakrishnan, Floyd A. Reed, and Joanna L. Mountain (2007) History of click-speaking populations of Africa inferred from mtDNA and Y chromosome genetic variation.

Molecular Biology and Evolution

20.10: 2180â2195. - Traill, Anthony (1994)

A !XoÌoÌ dictionary. Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung 9.

Cologne, Germany: RuÌdiger KoÌppe. - Wassman, J. and P. Dasen (1998) Balinese spatial orientation.

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute

4: 689â711.

- Andresen, Julie Tetel (2013)

Linguistics and Evolution. A Developmental Approach

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - Barrett, Louise, Robin Dunbar, and John Lycett (2002)

Human Evolutionary Psychology

. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. - Deacon, Terrance (1997)

The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain

. New York: W.W. Norton. - Lieberman, Phillip (1984)

The Biology and Evolution of Language

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. - Lieberman, Phillip (1991)

Uniquely Human: The Evolution of Speech, Thought, and Selfless Behavior

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. - Lieberman, Phillip (2000)

Human Language and Our Reptilian Brain: The Subcortical Bases of Speech, Syntax, and Thought

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. - Lieberman, Phillip (2006)

Toward an Evolutionary Biology of Language

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. - Maturana, Humberto and Francisco Varela (1980 [1972])

Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living

. Dordrecht, Netherlands: D. Reidel Publishing. - Maturana, Humberto and Francisco Varela (1992 [1987])

The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding, Revised Edition

, translated by Robert Paolucci. Boston: Shambhala. - Oyama, Susan (1985)

The Ontogeny of Information: Developmental Systems and Evolution

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - Oyama, Susan (2000)

Evolution's Eye: A Systems View of the BiologyâCulture Divide

. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. - Traill, Anthony (1985)

Phonetic and Phonological Studies of ÇXóõ Bushman

. Hamburg, Germany: Helmut Buske. - UCLA Phonetics Lab Archive. !xoo.

http://archive.phonetics.ucla.edu/Language/NMN/nmn.html

.

The Recorded Past

âCatching Up to Conditions' Made Visible

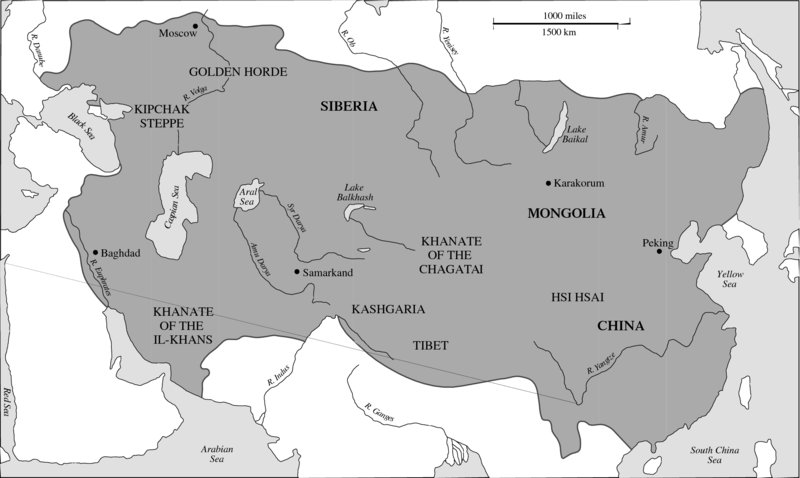

In the early thirteenth century, Genghis Khan united a variety of Mongolia's nomadic tribes. Because of the Mongolians' exceptional skill as horsemen, Genghis Khan was able to conquer many of his neighbors. In 1204, he subdued the Uyghur people in what is now Xinjiang, a western province of China. There, he captured a scribe named Tata-tyngaak and commanded him to adapt the Uyghur alphabet

1

to write Mongolian. The Mongols were such fierce horsemen they were able to conquer their neighbors in all directions (

Map 11.1

), such that by the time of Genghis Khan's grandson, Kubla Khan, the Mongolian Empire had spread west across the Eurasian steppe, as we saw in Chapter 8. In 1271, Kubla Khan established the Yuan Dynasty, the first foreign dynasty to rule all of China, which lasted almost another 100 years. Still today, the horse is important in Mongolia, and not only because they outnumber the people there by an order of four to one.

Map 11.1

The later Mongol conquests at their greatest extent: 1270.

Horses and horse culture are woven into the Mongolian language and thus exemplify the kind of ethnosyntax described in Chapter 2. The typical way to say âWelcome' in Mongolian is

tavtai morilnÉ oo!

Another, older way to say it is

morilooroi

, literally âcome by horse please.' Certainly, no one says this any more, because a Mongolian is now likely to arrive at a friend's house by car, bus, or other modern means. However, the word

mor

âhorse' is still found in the usual phrase

tavtai

mor

ilnÉ oo!

It is furthermore a gentle welcome,

tavtai

meaning âpeaceful' [arrival by horse]. The unremarkable word

bracelet

in Mongolian also reveals an equestrian connection. In English, the word was borrowed from French, and in French, the association is with

bras

âarm,' the location on the body where the bracelet is placed. In Mongolian,

bogoivÄ

âbracelet' is also associated with a body location, namely

bogoi

âwrist.' However, both of these words derive from the verb

bogoidax

âto lasso.' A bracelet is thus the action of

encircling the wrist with a rope. The Mongolians are never far, linguistically speaking, from their horses.

Why are horses relevant at the outset of Chapter 11? Because in this chapter, we endeavor to explain what we can of the specific ways languages catch up to conditions when we have historical records of them. We know what we know of the history of Mongolian because there are 800 years of recorded history. The Mongolian script is, furthermore, written vertically top to bottom and has the rhythmic curves it does because Genghis Khan wanted to make sure his scribes could write it while riding their horses. Now, there's a technological innovation to keep an empire up and running. In this chapter, we want to exploit the records produced by such technological innovations, including those of today's digital archives, in order to look more closely at how languages change over time. In Chapters 3 and 7, we outlined the principles and methods of historical reconstructions that give us a picture of languages before recorded history. Here, in Chapter 11, we examine what we can of language and language change when we have written and/or digital records at our disposal.

We now put the linguistic flesh on the bones of the various stories we have been telling throughout Chapters 3â9. Because the time period of Chapter 10 lies far outside written history, we cannot reconstruct any linguistic specifics for that chapter. We take each chapter in turn.

In the discussion of morphological typology, we noted English speakers' preference for the invariable word. This preference shows a particularly complex and delayed way in which language is always catching up to conditions. Old English, a West Germanic language, had rich inflectional morphology with five syntactic cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, and instrumental. As a result of the Danish invasions of England in the eighth and ninth centuries, the case system of Old English started to weaken as speakers of a North Germanic language, Old Norse, began to interact with the West Germanic speakers of Old English. Because the two languages' case (systems) did not fully agree, speakers became understandably confused. Often the oldest records of a Western European language are in the form of translations of Latin texts. However, Old English has unusually ample written records that are not translations of Latin texts, and so examples of the breakdown of the case system can be found in records of the ordinary language.

One example will suffice: the ninth-century manuscript known as

Oðere's Voyage

describes an account of a voyage into the North Sea by a man named Oðere. In the midst of the description, the following prepositional phrase stands out:

on ðæ

m

oðera

m

ðri

m

daga

s

âon the third day.' The first three words

ðæm oðeram ðrim

are in the dative plural case marked by a final -

m

, since they are in a phrase that begins with the preposition

on

. However, the head of that prepositional phrase, namely

dagas

âdays,' is not in the dative case but rather in the nominative. The so-called correct dative form would have been

dagu

m

, but evidently the writer of this account did not feel that

dagum

sounded right, despite the fact that the three preceding words had the final

-m

ending of the dative plural. Something about the noun

dagas

in this speaker's

mind could be separated and made distinct from the preceding adjectives modifying it. The breakdown of the case system took hundreds of years with thousands of speakers making millions of linguistic decisions moving in the same direction as the writer of OÄere's voyage.

The arrival of Norman French in England with William the Conqueror in the eleventh century took a further toll on Old English inflectional morphology, this time in the gender system. Old English had three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. By the time Norman French arrived in England, the PIE three-way gender system in French had decreased to two: masculine and feminine. Norman French for âthe flower' was

la flour

, a feminine noun. It so happened that Old English for âthe flower' was

Äæt bled

, a neuter noun. What were speakers to do in the face of such a clash? We know the answer. They replaced

bled

with

flour

and discarded the gender distinction. Incidentally, the Old Norse word for âflower' was

blom

, and English speakers borrowed that word as well. It has survived as

blossom

. The point is: the confusions and choices ensued until the eventual collapse of both the case and gender systems.

Hundreds of years later, speakers are still trying to level out the remaining differences in the case system of the pronouns, with the relative and interrogative pronoun

who/whom

distinction gone the way of the dodo easily 100 years ago or more, although it is still sometimes taught in classrooms. Eventually the current competition between

between you and me

and

between you and I

will sort itself out and no doubt in relation to which way the other pronouns go. Perhaps the leveling will be complete, and subject and object pronouns will have one form for all speakers. Or perhaps English will become diglossic with stable and salient H and L versions, with H reserving for itself the prestige of pronoun distinctions, and L the language of the home and/or the hoi polloi.

Whatever may happen to the pronouns, English speakers are still left with what might be called the historical wreckage, to speak here very metaphorically, of the synthetic Indo-European past. In Chapter 3, we compared English typologically to Chinese, the latter typing very nicely as an analytic language with little morphologic variation in its forms. In Chinese, the word âthree' is

san

, and the word âten' is

shÃ

, and they combine without morphological change in combinations to make both âthirteen' and âthirty.' English, by way of contrast, has not one but three forms of the concept âten':

ten

, -

teen

, and -

ty

and two forms of the concept âthree':

three

and

thir

-. English also retains pairs of words that hide the workings of a polysynthetic morphology, which means that it is difficult to separate out the different parts of the word-formation process, as in the relationship between

young

and

youth

,

foul

and

filth

,

broad

with

breadth

,

whole

or

hale

with

health

. Speakers do what they can with the materials at hand and the need to get through their day, and the languages they speak are fascinating refractions of imperfectly applied processes that nevertheless always seek some kind of grammatical equilibrium.

You will remember from Chapter 4 that during the French Revolution, Abbé Grégoire was determined to annihilate all forms of language in the newly forming nation-state

that were not

Ãle de la Cité

French. Two hundred years later, it is clear that he made an impact in reducing language variety in France. However, he did not succeed in wiping all non-Parisian forms of the language off the map. In any case, he was never going to be able to stop any, much less all, varieties of French from changing.

There is evidence that colloquial modern French is becoming a VSO language, given the quantity of utterances like:

| il | est | joli | ce coin |

| it | is | lovely | this corner |

| âthis area is lovely.' |

Such an utterance is a statement, and the subject

ce coin

comes after the verb. The (formerly) subject pronoun

il

âhe/it' is now functioning less like a subject pronoun and more like an agreement prefix. The transforming of both subject and object pronouns into clitics in French is occurring throughout informal speech. Although it is perfectly grammatical to say:

| je | connais | cet | homme |

| I | know | this | man |

it is more normal to say:

| je | le | connais | cet | homme |

| I | him | know | this | man |

where

le

is now an object pronoun. The point is that languages can and do change their word-order preferences over time. In the last 2000 years, the SOV preference of Latin has transformed into the SVO preference of spoken French, which is further transforming into a VSO language.

With regard to this shift to head-marking in progress in the grammar of French:

- it is a hallmark of the spoken language;

- it is pervasive and not limited only to subjects and objects but is also found in the genitive-type:

il

en

a marre Paul

des études

âhe (genitive

en

) has enough Paul of studies'/âPaul is tired of his studies'; - the change is more widespread in the southern half of France and so is presumably the place where the shift originated; and

- the grammatical information about the subject

ce coin

âthis corner,' which has not yet appeared, has already been signaled by the (soon-to-be former) pronoun

il

, which is migrating in spoken French toward becoming a clitic associated with the verb.

Now, notice one more thing: the order of the first three or four words â

il est joli

,

je le connais

,

il en a marre

â stays the same, as they are in standard/formal French. The syntax remains; the interpretation of the elements changes. These are good

examples of an adage well known to historical linguists: yesterday's syntax is tomorrow's morphology.

The question can now be asked: Is this head-marking shift related to other developments in the language? The answer given by Stephen Matthews, author of the article “French in Flux” (1989), is Yes. The reinterpretation of the pronoun

il

as a new clitic is related to other grammatical evidence that pronouns are generally being reinterpreted throughout the language. As mentioned in Chapter 8, French is the Romance language with the most radical phonology, that is, the most distant from Latin, with significant loss of endings both on nouns showing gender and verbs showing person. Given the erosion of the endings on verbs, personal pronouns have long been necessary to indicate who or what is doing something. With the exception of the second person plural/polite

vous

âyou' form, there is no audible difference in the overwhelming majority of verbs for the other persons. There is a visible written difference, but in French (as in English), writing preserves what were phonetic differences hundreds of years ago. Thus, today, the colloquial conjugation of

parler

âto speak' is:

| Singular | Plural | |

| First person | je parle [paÊl] | |

| Second person | tu parles [paÊl] | vous parlez [paÊle] |

| Third person (he/she) | il/elle parle [paÊl] | ils/elles parlent [paÊl] |

As you see, all forms of the verb are pronounced [paÊl] except for

vous parlez

âyou (plural/polite) speak,' which is [paÊle]. The form of the first person plural has been left blank, because leveling of endings on verbs has continued to now include a strong tendency for the first person plural

nous

âwe' to be doubled by the indefinite pronoun

on

âone.' In the phrase

nous on parle

âwe/one speaks,' the verb form is again [paÊl] and is opposed to the more formal/standard

nous parlons

where the form of the verb is [paÊlõ].

The point here is that although the personal pronouns operated for hundreds of years simply as personal pronouns, they now seem to be functioning overall as clitic markers. The once purely emphatic statement

moi je parle

â

I'm

speaking' was made by adding the stressed pronoun

moi

to the phrase. Now, however, the

je

seems to function as part of the verb as an agreement marker, and the

moi

is now there to indicate who is doing the speaking in a nonemphatic way. Further evidence that the personal pronouns have morphed into clitics can be seen in the fact that they cannot now be used deictically. When pointing to someone in English, it is perfectly natural to say: “She's French.” However, in French, you now have to say, “

Elle, elle est française

.” This doubling is redundant only if the second

elle

were actually (still functioning in the speaker's mind as) a pronoun. Finally, in the varieties where the head-marking shift is strongest, these (former) pronouns no longer undergo subjectâverb inversion in questions of the standard sort:

| Où | est | mon | livre ? | Où | est-il? |

| Where | is | my | book? | Where | is-it? |

The more normal spoken way to say this now is:

| Où | il | est | mon | livre ? |

| Where | it | is | my | book? |

Three points can now be made, all relevant to this chapter as a whole:

- When a grammatical change is taking place in a particular language, it does not do so all at once. Rather, changes occur item by item. For French, the changes in the pronouns may well have begun with the first person

moi je parle

, since it is the prototypical deictic expression, and then extended easily to the other persons

toi tu parles

,

lui il parle

, and

eux ils parlent

; what is interesting is to see how there has been parallel cliticization throughout the language. - What looks like doubling or even redundancy in

moi je parle

, where the âI' is marked twice (once with

moi

, a second time with

je

), is actually common cross-linguistically as a language shifts from dependent- to head-marking. - These new structures, these reinterpretations, often arise when a grammatical structure first used for a certain effect becomes so widespread that it loses its effect and becomes the norm.

It seems to be the case in French that these newer structures arose and are still most common in affective utterances, ones that have a stronger emotional pull on the speaker than other utterances. Matthews (1989:196) offers a host of examples:

| Je | l'aime | moi | Marie |

| I | her-love | me | Mary |

| âI love Mary' |

and

| il | est | joli | ce | coin |

| it | is | pretty | this | corner |

| âThis area is lovely ' |

as well as

| je | m'en | fiche | moi | de ce boulot |

| I | me-genitive | don't care | me | of this job |

| âI don't give a damn about this job,' |

along with other expressions of admiration, disapproval, annoyance, frustration, delight, and so forth.

Although the French language has not been affected by the series of invasions that so dramatically reformed English, it is the case that French, just like every other language, has its share of variants, because it has its share of speakers and speech communities. Out of these communities come the forms that are in play and available for

other speakers to either adopt or reject. It could very well be that the strong sense of standardized French in the north is (one of) the condition(s) the speakers in the south are pressing off and away from.