Languages In the World (32 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

Sino-Tibetan is one of the most important language stocks, given that it has the most speakers in the world today. The early Sino-Tibetans were a Neolithic people who lived in the central plains of what is now northern China, in the valley of the Yellow River. The time of their breakup is dated at about 6.5 kya, and the expansion was to the west and the south, with the southern movement also heading east. Those who stayed in the central plains or moved south and east became the group that has come to be known as Chinese, while those moving south and west have become known as the Tibeto-Burmans. Although there is archeological evidence dating back seven millennia, given the diversity of the modern varieties, the reconstruction of Proto-Chinese cannot date farther back than about the first millennium BCE. Proto-Sino-Tibetan was SOV. Tibeto-Burman languages have agglutinative morphology and a preference for postpostional inflectional morphology, and these features may also have been true of Proto-Sino-Tibetan. Modern varieties of Chinese, however, have little inflectional morphology and do not mark nouns for case or gender; they prefer compounding and derivational morphology.

Philologists now recognize the language stock known as Hmong-Mien, aka Miao-Yao, which includes languages spoken in central southern China. These languages used to be classed as Sino-Tibetan but are now understood to make a separate language family.

Paleo-Siberian is a term of convenience to refer to a collection of language isolates. Efforts have been made to sort out the geographic situation by identifying the family Yeniseian (Ket) whose homeland is likely the Yenisei River in central Siberia and which may not be more than 2000 years old. Chukotko-Kamchatkam (Chukchi) is another family identified as belonging to this region. Among the many other languages to be found here are Yukaghir and some varieties of Eskimo-Aleut.

There is no homeland as such that can be posited for speakers of Native American languages. In the 1960s, philologist Joseph Greenberg proposed three waves of human movement across the Behring Straights that produced three linguistic divisions: (i) the first around 30 kya, which forms the group of General Indian and encompasses most of the languages found on the two continents; (ii) a second around 15 kya, which brought a much narrower linguistic group/stock called Na-Dené that includes the language family Athabaskan (Apache, Navajo) â Athabaskan languages are spoken in Alaska and British Columbia, and the southwestern United States; and (iii) a more recent migration, perhaps around 6 kya, to present-day Canada, bringing languages that come under the heading of the stock Eskimo-Aleut (Inuit). These are spoken from Siberia to Greenland. With the American Indian languages, as is the case for the Aboriginal Australian, Indo-Pacific, and Khoisan languages, we are out of reach of what the reconstructive method can tell us about more precise relationships among many of the Native American languages.

Nevertheless, biologists reached similar conclusions about the peopling of the Americas. Before the advent of DNA sequencing, blood typing was used to identify human groups, and it was noted early on that for indigenous populations of Central and South America, Blood Type O was found 100% of the time and nearly 100% of the time for indigenous populations within the United States. The blood-type picture changed for indigenous populations in Canada. DNA studies have reinforced the idea that the first populations to move into the New World formed a distinct group and remained in isolation because they belonged to a single Y-haplogroup, while the Na-Dené and Eskimo-Aleut belonged to a different Y-haplogroup.

Despite these coincidences with biology, Greenberg's three large groups are not universally accepted. That is to say that the subject of the historical relationships among the Native American languages is very complex indeed. Difficulties immediately arise in how to break down these three large groups into language stocks. Some of the stocks of the General Indian (if one accepts such a grouping) are relatively well defined, for instance Algonquin (Delaware, Massachusetts, Menomini) once spoken across much of the eastern seaboard of the United States and across the Mid West, and Iroquois (Wyandot, Seneca, Oneida, Cherokee) once spoken in what is Upstate New York, Quebec, and Western North Carolina and, after the Trail of Tears of the 1830s, now

in Oklahoma. Another established language stock is Uto-Aztecan (Nahuatl) found in the western United States and Mexico. Proto-Uto-Aztecan dates to around 5600 years ago and seems to be a family that spread after the domestication of maize â¼5 kya. However, not all the native languages identified in North America can be assigned to a clear family or stock.

The language map of South America is even more complex than the language situation in both North America and Southeast Asia. The Amazon Basin alone contains about 300 divided into 12 language stocks and some language isolates. The major language families are: Arawak, TupÃ, Carib, Pano, Tucano, and Jê. The languages of this region are not easy to categorize. One specialist in these languages, Alexandra Aikenvald, has likened the Amazon to a set of Chinese boxes of linguistic areas and subareas, included within each other. For convenience, we treat the Native American languages as an areal grouping.

When we began our discussion of philology and Indo-European in Chapter 3, we tried to make things as clear-cut as possible. However, the further one goes into the relationships among the branches of any language family and the further one goes back in time, the less clear-cut everything becomes. This might also be called the fun of being a philologist. The brief discussion of the Native American languages begins with the identification of the grouping General Indian, which could be called a phylum or even a macrophylum, a term we are using for a classification that has a time-depth of 15â40 kya or more.

16

Whatever the precise time-depth, they are large-scale classifications whose subgroupings do not form clear branches and subbranches. Phyla and macrophyla are hypotheses about how humans who were moving around during the period of Globalization 1.0 interacted with one another before settling down in the aforementioned fairly well-agreed-upon language stocks. The phyla and macrophyla are based on assumptions about the ways groups of people interact when they migrate and the linguistic results of those interactions. These assumptions about movement patterns and language change form the way the relationships among the languages are represented. There have been two major ways these relationships have been imagined and then represented: by means of trees and by means of waves.

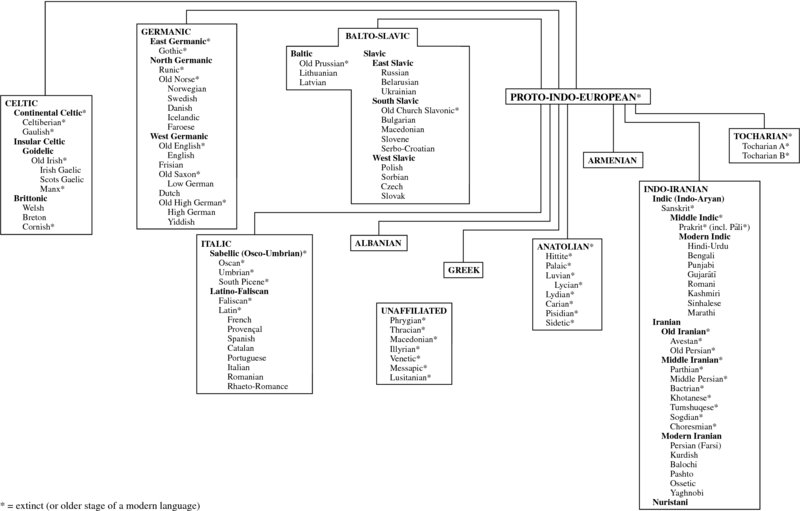

The usual representation of the relationships among languages in a language family is the tree model (

Figure 7.2

), one of splitting and branching, as a continuous and ongoing differentiation. We have been, more or less, assuming this model in our discussion of both linguistic and population separations. Nineteenth-century philologists understood that the tree model is good for representing the splitting process that results in linguistic differentiation, say, when the Germanic tribes left the PIE homeland and began to travel west and north. A catalogue of features particular to Germanic can be made, for instance: (i) phonetic effects of Grimm's Law; (ii) a third of its vocabulary being of non-PIE origin; (iii) a unique system of strong verbs (

sing-sang-sung

)

and weak verbs (

walk-walked

). Incidentally, the image of the tree is the only image Darwin included in his

Origin of the Species

, and it has consolidated itself linguistically when we speak of our individual or collective

family tree

. The tree's venerability, however, is no reason to limit ourselves to it.

Figure 7.2

Tree model image.

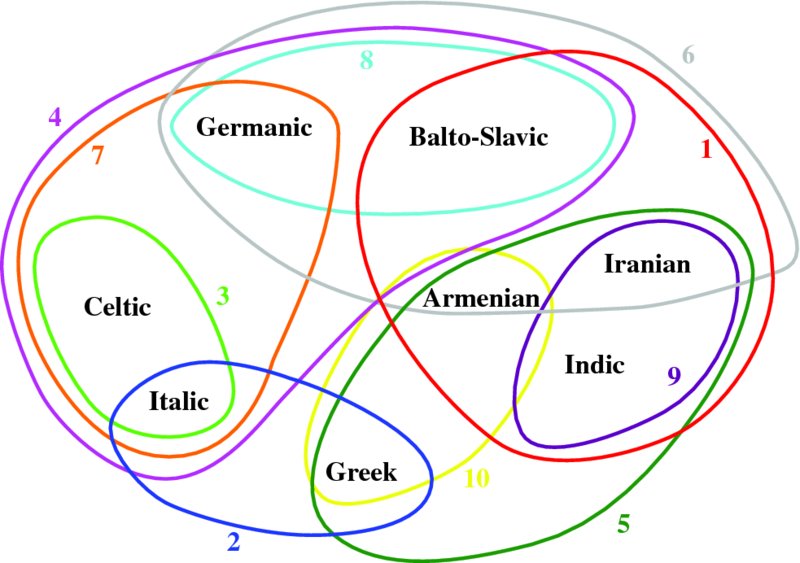

Nineteenth-century philologists knew that the tree model fails to represent linguistic changes that spread, like waves (

Figure 7.3

), over a speech-area, and various changes may extend over different parts of an area that do not coincide with the parts covered by earlier changes. Germanic and Italic, for instance, share the feature of using the perfect tense as a general past tense, while Germanic and Balto-Slavic coincide in a nasal bilabial case ending -m from

*

b

h

, a PIE voiced aspirated bilabial stop. Celtic and Italic share passive voice endings with -r#, while Greek, Armenian, and Indo-Iranian prefix #e- for past tenses. Greek and Latin have feminine nouns with masculine suffixes, that is, quite a few more than the word for âdaughter-in-law,' and so on. The tree model cannot capture these historical relationships.

Figure 7.3

Wave model image.

The choice between the tree and the wave may well come down to aesthetic preference, whether one prefers straight lines or wavy lines, and to cognitive style, whether one is a lumper or a splitter. Of course, neither aesthetics nor style can trump careful analysis of evidence. And to repeat, the methods of linguistic reconstruction work only up to a time-depth of 10 kya. Beyond that, no graphic model is appropriate, and only statistical analyses of certain structural features can provide any possibility of linguistic relatedness, as we will see in Chapter 10.

The most important take-away from this chapter about the effects of movement is this: when a group of people who once lived together for a long period of time begins to disperse, and the people migrate away from one another, the long-term linguistic result is

isolation

. Because languages are permeable systems responsive to the ever-changing conditions of their speakers, the physical divergence of a group of

people will also produce a linguistic divergence in their ways of speaking. The effects of dispersal from a homeland are apparent in new and distinct daughter languages, separated by time and space and mutual intelligibility.

As we have just seen, most of the world's languages can be grouped into families. There are, however, languages with no known historical relationship to a family, and these are called

isolates

. Korean and Japanese are sometimes classed in the phylum Altaic. However, although Korean does have similarities with other languages in the Altaic family, there is no definitive evidence whether those similarities were inherited from the protolanguage or were acquired by contact. Japanese also has similarities with Altaic languages, but it shares features with other languages in the region as well. Clearly, both of these languages are well known and well studied, but having large numbers of speakers and well-developed histories and literatures does not guarantee a language family classification.

17

More often, a language is classed as an isolate because not enough is known about it either linguistically or historically. For instance, the Etruscan language was spoken in Italy before the Roman Empire flourished. The Etruscans handed down to the Romans the alphabet they had borrowed from the Greeks and adapted to their own use. Thousands of Etruscan inscriptions have survived. However, not enough have been deciphered to know what kind of language Etruscan was. The transcriptions petered out in the third century BCE. Another isolate is Sumerian, the oldest-known language to be preserved in written form. While its copious records written in cuneiform dating to 3300 BCE have been deciphered, there is still no way to connect it to a definite family, although Altaic and Dravidian have been suggested. Sumerian was spoken in Mesopotamia before it was replaced by Akkadian, a Semitic language in the Afro-Asiatic stock.

Two language isolates are found on the Iberian peninsula. The first is Iberian, which was spoken in southern and eastern Spain in pre-Roman times. The inscriptions that have been discovered in that language have not been successfully interpreted. However, the language was written in an alphabet with distinct Greek and Phoenician influences. The other isolate, Basque, is still spoken today in northern Spain and southwestern France, and because this language is a living isolate in Europe, it has been the subject of intense interest. One unresolved question is whether Basque is related to Iberian. An early suggestion was that Basque had similarities to languages spoken in the Caucasus. The fact that the Greeks used the term

Iberes

to refer to the people of the Caucasus gave rise to the idea that they were connected with the

Iberi

of Spain. There are linguistic features as well to tie the two, such as ergativity, which is found in both Basque and Georgian, but no lexical similarities can be found.

To try to understand to whom the Basques might be related, we turn to population genetics, and the work of Luigi Cavalli-Sforza who has mapped out the frequencies of various alleles of many genes to determine the related among populations. Because the Basques have practiced endogamy (marrying within the group) for a very long time, Cavalli-Sforza (2000:112, 121) and his team have been able to propose that the Basques are likely descended from Paleolithic and then Mesolithic people living

in Europe before the arrival of Neolithic people. During the Paleolithic period, the Basques likely occupied the areas where the cave paintings have been found. These were the first, preagricultural Europeans; they were the first people to occupy present-day France 40â35 kya and probably migrated there from the southwest, although it is possible they came from the east, as well.

18

As a point of information, the Basques call their language

Euskera

.