Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (39 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

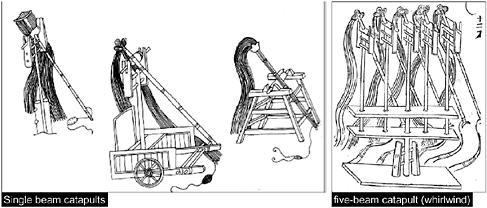

Chinese siege machines can be divided into three main categories: catapults that fired round clay balls;

24

siege machines that hurled inflammable materials; and large and powerful crossbows.

The Pao: the Chinese catapult

The word

Pao

(

Phao

), means literally to hurl or to throw. The Pao was mounted on a base that resembled a pyramid or a light cart, which made maneuvering it during a siege a slightly easier task. The type of wood used for the central arm was of great importance; in most cases it was either oak or black birch, soaked in water for at least six months. The length of the central beam varied between 5.58 and 7.75m. One end had a leather sling that held the catapult-stone and the other had ropes to pull on. A more advanced type of catapult machine had several beams and could hurl five or seven stones simultaneously (

Figure 2.1

).

25

This latter type of siege machine does not appear to have been known among the Franks or the Mamluks. In addition, there were also siege machines where the beam was mounted on an axis, enabling the machine to be aimed in different directions without having to move the entire structure. Most siege machines were built on those basic lines. The main difference between the various types was in the length of the central beam and the number of beams. Those two components dictated the number of men needed to operate the

Figure 2.1

Chinese siege machines in the twelfth to thirteenth centuries

machine and the weight of the stones that could be hurled.

Table 2.1

lists the various types of siege machines and the number of men needed to operate them, the distance each machine could fire and the weight of the stone or clay projectiles.

A number of historical narratives concerning the Mongol invasion into the Middle East provide information that does not comply with the figures given in the above table. However, the figures proposed provide a reliable basis for estimating the force of Chinese siege machines. An interesting aspect of Chinese siege machines is the use of clay balls as projectiles. This was recommended by Ch’en Kuei (ca. ad 1130), author of the twelfth-century war manual

Shou-ch’eng lu

.

26

The counterweight siege machine first appeared in China during Qubilai’s reign (1260–94). We have no written evidence of the use of counterweight siege machines by the Īlkhānids other than an illustration in the manuscript of the

Jāmī‘ al-tawārīkh

(dated 1306–14) at the Edinburgh University Library.

27

The most convincing evidence of the penetration of Islamic siege technology from Syria to the Īlkhānid state and further into the Chinese Empire is dated 1272. During Qubilai’s wars against the Song state he had sought the advice and help of his nephew, the Īlkhān Abagha,

Table 2.1

Chinese siege machines in the service of the Mongol army

Number of men on the crew | Weight of stones in kg. | Range in meters | Type of siege machine and number of beams |

40 | 1.2 | 86.75 | single-beam catapult |

50 | 1.8 | 86.75 | five-beam catapult (whirlwind) |

70 | 7.2 | 86.75 | single beam (crouching tiger) |

100 | 15 | 104 | two-beam catapult |

70–80 | 94.2 | 86.75 | five-beam catapult |

90–100 | 150 | 86.75 | seven-beam catapult |

Source: This table is based o |

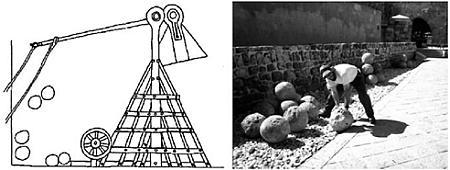

Figure 2.2

The counterweight trebuchet and catapult stones from the siege of Acre, 1292

asking for two Muslim siege engineers to be sent to his court.

28

This request indicates that siege technology in the Eastern Mediterranean was more advanced than that of the Īlkhānid state and of the Chinese siege units employed by Qubilai. We may also conclude that the Īlkhānid army had begun to use the counterweight trebuchet soon after the state was established. Two Muslim engineers who specialized in building siege machines were brought to Qubilai’s court in 1272. was from Mayyāfarīqin and

was from Mayyāfarīqin and from Aleppo. At the court they built what is known in the Mamluk sources as “the large Frankish manjanīq”; in China it received the title “the Muslim phao.”

from Aleppo. At the court they built what is known in the Mamluk sources as “the large Frankish manjanīq”; in China it received the title “the Muslim phao.”

A description of this siege machine is given in the

Yuan-Shi

. Its main advantages were that it did not require a large team; the projectiles were considerably heavier and could cover a greater distance. The eight of the stones could reach 90kg and more.

29

According to the source, when they hit the ground they made craters that measured 2.17m in diameter. The sound toe through the sky and the earth and the damage was considerable.

30

This appears to be the first Chinese description, if somewhat exaggerated, of the counterweight trebuchet (

Figure 2.2

).

Inflammable materials

In addition to stone and clay projectiles, vessels containing inflammable materials were a favorite type of ammunition in Chinese siege warfare.

31

Certain siege machines had names such as “Hao Pao,” i.e. a fire-hurling siege machine. Pots with wicks of flax or cotton were used, containing a combination of sulphur, saltpeter (potassium nitrate), aconite,

32

oil, resin, ground charcoal and wax. This recipe in fact contains all the basic ingredients for making gunpowder, but the emphasis in the recipe given above was on producing toxic fumes; it was called “tu-yao yen-ch’iu,” literally a ball of smoke and fire.

33

The frequent use of inflammable materials in Chinese siege warfare was most probably due to the fact that a large percentage of both public and private buildings were constructed of wood and bamboo. Even houses made of mud bricks had a wooden frame. In addition to clay roof tiles, thatched roofs could be found in both northern

and southern China. The materials used for thatching included straw from wheat or rice, canes and various types of wild grass.

34

It is no wonder then that the main dread of the besieged was of fires inside the city. Pots containing inflammable materials were hurled into a densely populated city where many structures were of wood.

35

Occasionally, even the city towers along the curtain walls were a combination of bricks and wood;

36

this can be seen in illustrations of the city Shao Hsing dating to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. A few examples of wooden gate towers date to the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries.

37

In some cases a high wooden palisade was erected parallel to the stone or brick curtain wall.

38

The immense destruction caused to the city of Bukhara when it was besieged by Chinggis Khan illustrates the effectiveness of inflammable materials in siege warfare.

He [Chinggis-Khan] now gave orders for all quarters of the town to be set on fire; and since the houses were built entirely of wood, within several days the greater part of the town had been consumed, with the exception of the Friday mosque and some of the palaces, which were built with baked bricks … mangonels were erected, bows bent and stones and arrows discharged … For days they fought in this manner.

39

In contrast to the widespread custom in large parts of China and some parts of Central Asia of building with wood and cane, in the Eastern Mediterranean public, private and military buildings were constructed mainly of stone.

40

This was both plentiful and relatively cheap when compared to the price of wood. Although inflammable materials were used in siege warfare by the Ayyubids, the Franks and the Mamluks, their effect was considerably less disastrous.

At this point of the discussion we should note that the most common material for the construction of curtain walls in China and Central Asia was rammed earth sometimes faced with stone and/or sun-dried mud bricks (

Map 2.1

and

Figure 2.3

).

41

In contrast to Middle Eastern and European strongholds that were built on prominent sites (hills, mountains, cliffs and the like) “no such preference for an elevated, easily defensible site, however, seems to have nourished city site selection in China.”

42

According to Di Cosmo, wall building was a military concept and a technology that originated on the Central Plain. Walls asserted the state’s political and military control over certain areas. “Like roads, walls provide the logistic infrastructure to facilitate communications and transportation, vital elements for armies employed in the occupation or invasion of foreign territory.”

43

This function attributed to walls in China differs from their function in the Eastern Mediterranean. Chinese walls were not constructed only for military purposes. They ere often located on a river bank and their first and at times most important task was to protect the population from floods. In certain areas in the northwest the walls acted as screens against sand storms.

44

Forbidding earthen ramparts almost became the trademark of Chinese fortifications, although certain sections such as the gates and towers were constructed of bricks or stone. Although they were effective their main fault was the large area of “dead space” below the wall. The straight lines and relatively few towers did not provide the defenders with sufficient flanking fire.

45