OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide (11 page)

Read OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide Online

Authors: Chris Seibold

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Operating Systems / Macintosh

Some features of Mountain Lion are really useful but not strictly

required for day-to-day use. Spotlight is fantastic for searching your

Mac, but some folks never need to search because they have insanely good

organizational skills. Mission Control lets you see everything on your

desktop (and more) at the same time—a lifesaver for those who work with

multiple windows. If you’re interested in one or more of these features,

this is the place to look.

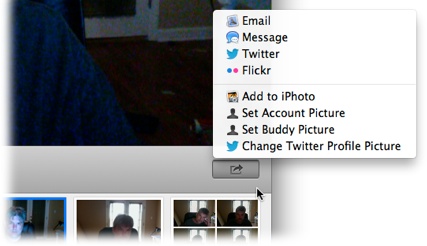

One of the big changes in Mountain Lion is that it gives

you the ability to share things easily and in multiple ways. Mountain

Lion accomplishes this by adding a feature called Share Sheets to most

applications. You access Share Sheets by clicking the Share button,

which doesn’t always look

exactly

the same (it

matches the app you’re using), but it resembles

Figure 3-28

.

When you see that icon, it means you can share whatever you’re

looking at with the world. Click the Share button and see your options

for spreading the word about your new favorite thing.

Figure 3-29

shows how you can

share an image from Photo Booth.

Figure 3-28. The Share button (and Trash icon) in Notes

Figure 3-29. Photo Booth offers a ton of sharing options

Before you’ll get options to share on Twitter, you have

to sign into Twitter. Once Mountain Lion sees you accessing Twitter,

it’ll ask if you want it to remember your Twitter info. If you choose

Yes, the system will add Twitter to your Share Sheets (where

applicable).

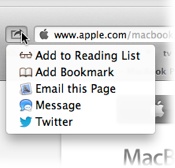

The exact options you see on the Share Sheet depend on the app

you’re using: The ways you can share something from Notes are different

from the ways you can share something from Safari, for example. (See

Figure 3-30

.)

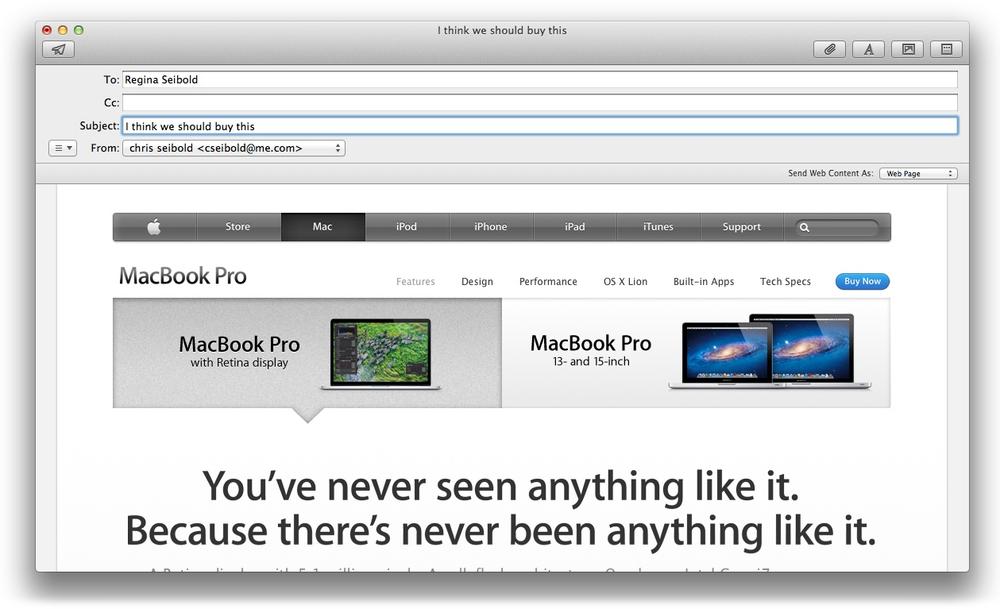

Even the information you can share differs depending on the share

methods you choose. If you decide to email a web page to some friends,

for example, the result will be an email message with the contents of

that web page; it will look something like

Figure 3-31

.

Figure 3-30. Sharing a web page from Safari

Figure 3-31. Sharing a subtle present suggestion

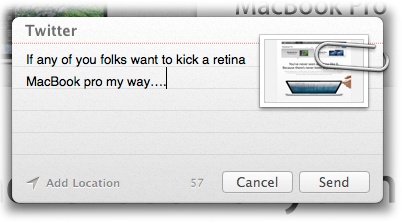

If you choose to share the same web page via Messages instead,

you’ll just send the link to the recipients. If you opt to send the page

to your followers using Twitter, you’ll send out something that looks

like

Figure 3-32

and have the option to add your

location.

Figure 3-32. Tweeting a link

Not every app can share, though. Apps included with Mountain Lion

that can share include Notes, Reminders, iPhoto, Photo Booth (you can

even change your Twitter picture directly from Photo Booth), Safari, and

FaceTime. And sharing isn’t limited to apps created by Apple—other

developers will be able to use the new sharing options built into

Mountain Lion, too. To figure out whether an app can share, just look

for the Share button.

Auto Save and Versions were introduced in Lion. Auto Save

does exactly what its name implies: as you work on a document, song,

movie, or whatever, Auto Save automatically saves your progress

incrementally so you don’t have to. Working in TextEdit and just want to

quit? You don’t need to save before quitting—Auto Save will save your work

without being told to.

Versions are the result of all those saves. With Versions,

if there’s a change you want to undo, you aren’t stuck with the most

recent version of your file. Use TextEdit as an example. Once you create a

document and start typing in it, the word “Edited” appears in the title

bar to let you know that Auto Save is working. Click Edited to reveal a

drop-down menu that gives you six options:

- Rename...

You can guess what this does: it lets you give the

document you’re working on a new name.- Move To...

Lets you choose where you want to save the document.

iCloud is an option, naturally.- Duplicate

Choosing this option lets you create a copy of the

current version of the file you’re working on and save it to a new

location.- Lock

This option lets you lock the document. Once it’s

locked, you won’t be able to edit it, but you can use it as a

template for a new document. Think of this as a way of being sure

you don’t make any boneheaded changes to something you worked long

and hard to create.- Last Saved

Choosing this item reverts to the last version you

explicitly saved with the Save command (not the latest version that

Auto Save created).- Browse All Versions

This is where Versions comes in. If you’ve made some

changes to your file that you like and some that you hate, you can

use Versions to pick out the moment in time when your file was at

its best. Select this option from the drop-down menu and you’ll see

a screen reminiscent of Time Machine. You can then flip through the

incremental changes Mountain Lion has been tracking and pick out the

version you like the most.

Not every application works with Auto Save, so don’t depend on

Auto Save to back up your work unless you’re

sure

the program you’re using supports it.

Auto Save and Versions work with iCloud as well, so if you’ve saved

your document to iCloud it is automatically updated on the cloud.

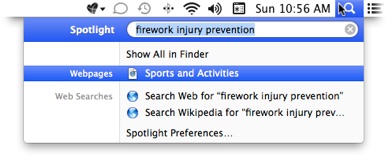

Using Spotlight is easy: Simply click the magnifying glass

icon in the upper-right corner of your screen and start typing the name

of the item you’re looking for.

In Snow Leopard, Spotlight lets you search through only the files

on your computer. But these days, it also lets you search the Web or

Wikipedia, as shown in

Figure 3-33

. (The results will

open with OS X’s Dictionary application.) You also get Quick Look

previews: just highlight the most promising-looking results and Quick

Look will give you a detailed look at the file or web page. Plus, you

can drag and drop things directly from Spotlight. Found that GarageBand

file you want to send to your pal? Drag it right to AirDrop to make the

process quick and painless.

When it’s searching your computer, Spotlight works by indexing

(making a list of) all the files on your Mac according to the files’

metadata and contents. So if you type “Lake Monsters Stole My Thursday”

into a document, that bit of data will be available to Spotlight. The

moment you type “lake monsters stole” into Spotlight’s search field,

you’ll see a list of matching files. By the time you’ve typed the entire

string into Spotlight, the document where you wrote it will be the top

result.

Figure 3-33. Choose where you want your results to come from

About Metadata

Metadata is information about a file. This includes

obvious things like the date it was created and its file type, as well

as a lot of unexpected info. An image’s metadata, for example,

contains information about its size, pixel count, and so on. Spotlight

is smart enough to realize that when you’re searching, you’re most

likely searching for a particular file’s name or contents, as opposed

to more esoteric metadata. So, while Spotlight indexes everything

(unless you tell it not to—see below), it puts results like documents

and folders higher on its lists of results than more obscure matches

(unless you change the order of its results—see below). That way, you

won’t be burdened by information overload when performing Spotlight

searches.

You can adjust how Spotlight arranges its results either

by choosing →

→

System

Preferences

→

Spotlight

→

Search Results or clicking Spotlight

Preferences at the bottom of any list of Spotlight search results. In

the window that appears, drag the categories into your preferred

order.

If you don’t want your Spotlight search results

cluttered with stuff you’re not interested in, go to →

→

System Preferences

→

Spotlight

→

Search Results and uncheck the boxes next to

any categories you find less than compelling. Be aware that not

returning results from certain categories doesn’t mean those files

aren’t indexed; read on to learn how to control

what

Spotlight indexes.

There are some things you just don’t want indexed: your

plans for world domination, your Pog value spreadsheet, and so forth.

To keep the things you want private out of Spotlight’s index, go to →

→

System

Preferences

→

Spotlight

→

Privacy. Clicking the + button brings up a

file-browsing window where you can select things you want to keep

Spotlight from indexing. You can exclude folders or entire disks.

Unfortunately, you can’t exclude a single file, so if you’re trying to

keep just one file out of the index, you either have to exclude the

folder it’s in (along with all of the folder’s other contents) or move

it into its own folder and exclude that.

As you learned above, Spotlight works by indexing

metadata. What if you want to add some metadata so Spotlight can find

files or folders with greater precision? The Info window is your key to

adding metadata (and changing other things, too). To open an item’s Info

window, select the item in the Finder and then either select File

→

Get Info or press ⌘-I. The window that appears

will look something like

Figure 3-34

.

Figure 3-34. Get Info is a very useful window

This window has several subsections:

- Spotlight comments

Spotlight will index anything you type here and use it when

it searches.- General

This section includes pertinent data about the file

(if this section is collapsed, click the disclosure triangle next

to the word “General”). If you check the “Stationery pad” box

(which appears only when applicable), the file turns into a

read-only file, meaning you can look at it and save it as a new

file, but you can’t save it with the same name as the Stationery

pad; this effectively turns the file into a template. If you’re

constantly tweaking the same document, you can use the template

you created by checking the Stationery pad box as a starting

point. (For example, if you are constantly generating TPS reports

but you change only the last page, you can mark the document as a

Stationery pad. You can then open it and add what you need to

without worrying about corrupting the master file.) Checking the

Locked box locks the file. A locked file is much like a Stationery

Pad except you can’t easily throw it away. You’ll get warnings

when you move a locked file to the Trash and again when you go to

empty the Trash.- More Info

Clicking the More Info disclosure triangle reveals where the

file originated if it wasn’t created on your Mac. (The file shown

in

Figure 3-34

happens to

be the chapter you’re reading.)- Name & Extension

This section lets you rename the item and hide its

extension. You can also change the extension, but that will

(likely) change which program opens the file. If you change the

extension, you’ll get a warning from OS X.- Open with

This section is surprisingly powerful. You can

choose the application you want to open this particular file with,

or change what programs open any file with the same extension by

clicking Change All. Clicking the pop-up menu will reveal

suggested choices, but if you don’t want to trust OS X’s advice,

you can select Other to force a different application to open that

file.- Preview

This section shows the same preview of the file that you see

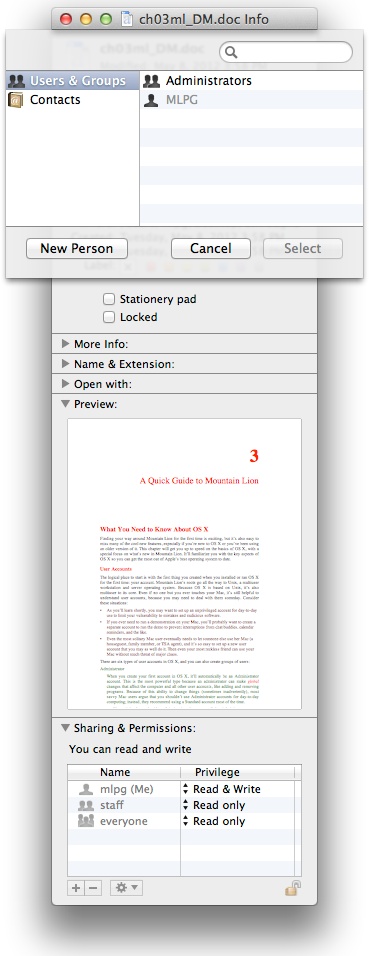

when using the Finder.- Sharing & Permissions

This is where you can fine-tune access to the file.

The options you’re first presented with differ depending on the

file, but generally include your account, an admin, and everyone.

Those are usually enough, but if you

really

want to control who can and can’t mess with a particular file,

click the + button to bring up even more options, as shown in

Figure 3-35

.

Figure 3-35. Fine-tuning who can share a file

In the window that appears, you can grant access to specific

individuals. Note that adding someone new (from your Address Book,

for instance) will bring up a dialog box where you can set a

password for the item, and will add a Sharing account to your Mac

for that person. Adding a new group of people will add a new Group

account.Finally, if you’ve made a bunch of changes to sharing and

then thought better of it, you can click the gear icon at the

bottom of the Info window and then undo what you’ve wrought by

selecting “Revert changes.”

The Sharing & Permissions section also includes a lock icon.

If you’re logged in as a Standard user, you can click it to unlock

restricted features, such as the Change All button in the “Open with”

section. However, you’ll need the username and password of an

administrative user to make those changes.