OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide (14 page)

Read OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide Online

Authors: Chris Seibold

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Operating Systems / Macintosh

Out of the box, the Mac is a fantastic machine. Its graphical

interface is clean and uncluttered, you can use it to accomplish tasks with

a minimum of frustration, and everything performs exactly how you expect it

to. That honeymoon lasts for somewhere between 10 seconds and a week. While

everything is great at first, you’ll soon find yourself saying, “Man, it

sure would be better if....” When this happens, your first stop should be

System Preferences.

Apple knows that different people want different behaviors from their

Macs. While Mountain Lion can’t possibly accommodate everything that

everyone might want to do, most of the changes you’re likely to want to make

are built right into Mountain Lion.

System Preferences, which you can get to by clicking the silver-framed

gears icon in the Dock (unless you’ve removed it from the Dock, in which

case you can find it in the Applications folder or the menu), is the place to make your Mac uniquely yours.

menu), is the place to make your Mac uniquely yours.

But as you’ll see later in this chapter, you can also make some tweaks by

going beyond System Preferences.

One thing that will inevitably happen while you’re adjusting

your System Preferences is that you’ll make a change and later decide that

it was a mistake. For example, say you adjust the time it takes for your Mac

to go to sleep and later decide that Apple had it right out of the box.

Fortunately, some preference panes feature a Restore Defaults button that

resets the settings in that particular pane to the factory defaults.

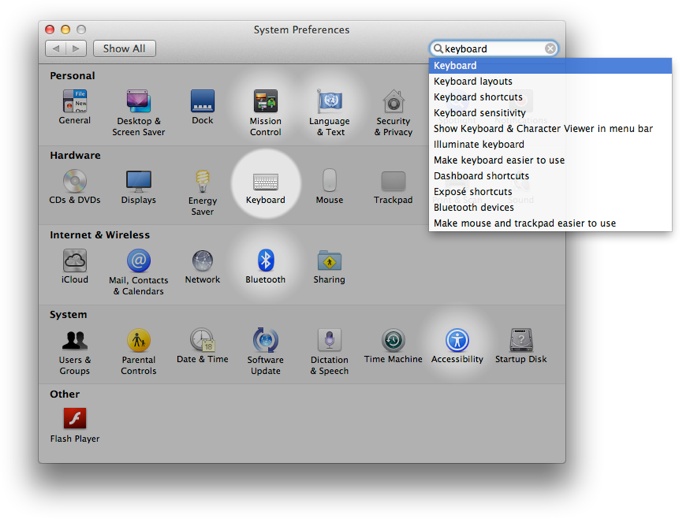

Mountain Lion comes with 29 preference panes, each of which

controls a bevy of related preferences. With all those options, how will you

remember where to find every setting? For example, are the settings for

display sleep under Energy Saver or Displays? Mountain Lion makes it easy to

find the right preference pane by including a search box right in the System

Preferences window (OS X is big on search boxes). Type in what you’re

looking for; the likely choices get highlighted, and you’ll see a list of

suggested searches (

Figure 5-1

).

Figure 5-1. Likely candidates for keyboard-related preferences

Try searching for one term at a time. For example, if you can’t find

the settings for putting your display to sleep by searching for “display

sleep,” try searching for “display” or “sleep” instead.

With so many preference panes, it’s hard to keep track of

what they all do. This section describes each one.

The System Preferences window is divided into five categories:

Personal, Hardware, Internet & Wireless, System, and Other. However,

you may see only the first four because the Other category is reserved for

non-Apple preference panes and doesn’t appear until you’ve installed at

least one third-party preference pane (which usually, but not always, is

part of a third-party application).

Some preferences, such as those that affect all users of the

computer, need to be unlocked before you can tweak them. (If a preference

pane is locked, there will be a lock icon in its lower left.) These can be

unlocked only by a user who has administrative access. On most Macs, the

first user you create has those privileges. If you don’t have

administrative privileges, you’ll need to find the person who

does

and have him or her type in the username and

password before you can make changes.

This preference pane lets you tweak the look and feel of

OS X. The first two options control colors. The Appearance setting

controls the overall look of buttons, menus, and windows and has two

choices: blue or gray. The Highlight setting controls the color used for

text you’ve selected and offers more choices, including selecting your

own color (choose Other).

And the “Sidebar icon size” setting lets you adjust, well,

the size of the icons in OS X’s various sidebars. (The most obvious

sidebar is in the Finder, but if you adjust this setting, other

sidebars—like Mail’s—will also change.)

The second section of this pane lets you decide when you

want the scroll bar to show up. “Automatically based on mouse or

trackpad” leaves the decision up to your Mac; “When scrolling” means the

bars show up only when you’re actively scrolling; and, for those who long for the

days of Snow Leopard, “Always” keeps them visible all the time. No

matter which option you choose, you’re stuck with gray scroll bars—no

more colorful scrolling.

You’ll also find options to modify what happens when you click a

scroll bar. You can set it to automatically jump to the next page or to

the spot that you clicked. The difference between these options isn’t

trivial: if you’re looking at a lengthy web page or a 1,000-page

document, opting for “Jump to next page” means it’ll take a lot of

clicks to reach the end, whereas “Jump to the spot that’s clicked” could

shoot all the way to the end in a flash.

By default, Mountain Lion shows your 10 most recent

applications, documents, and servers in the menu’s Recent Items submenu, but you can change

menu’s Recent Items submenu, but you can change

that number here.

The Desktop & Screen Saver preference pane has two

tabs. The Desktop tab lets you change the desktop background (also known

as wallpaper). You can use the Apple-supplied images, solid colors

(click Custom Color to create your own), or pictures from your iPhoto

library. You can even specify a whole folder of images by clicking the +

button in the tab’s lower-left corner.

If you’re using multiple monitors and invoke this preference

pane, your Mac will open one window on each monitor. You guessed it:

this lets you control the desktop picture and color for each monitor

individually!

If you pick an image of your own, you can control how it’s

displayed by selecting Fill Screen, Fit to Screen, Stretch to Fill

Screen, Center, or Tile from the menu to the right of the image preview.

If you like a little liveliness, you can tell your computer to change

the desktop picture periodically. Apple supplies options ranging from

every five seconds to every time you log in or wake from sleep. And if

you want your menu bar to be solid instead of see-through, turn off the

“Translucent menu bar” checkbox.

If you choose to change the picture periodically without

carefully vetting the source images, you’ll likely be presented with

something completely useless, confusing, or embarrassing at a random

moment.

The Screen Saver tab is a bit more complicated. In the

left half of the pane, you’ll find a long list of slideshows (14

different styles, to be exact). Select a slideshow style and, in the

right side, you’ll see a Source pop-up menu that lets you tell the

slideshow to use images from one of four default collections (National

Geographic, Aerial, Cosmos, Nature Patterns) that all look fantastic.

You can also pick a folder for the slideshow to use. Finally you’ll see

a “Shuffle slide order” checkbox, which you should check if you grow

tired of the same progression of pictures time after time.

If you scroll past the 14 slideshow options, you’ll discover

Screen Savers. Your choices are limited to only six option (seven if you

count Random). Select the screen saver you want your Mac to use, and

you’re done. Well, maybe not—depending on the screen saver you choose,

you might get options. If that is the case, the Screen Saver Options

button in the right side of the pane becomes clickable. Clicking it lets

you set options for that screen

saver.

Below the area where you choose slideshows and screen

savers, you’ll find a pop-up menu labeled Start After which allows you

to control how long your Mac is idle before displaying your chosen

slideshow or screen saver. You’ll also find a checkbox labeled “Show

with clock,” which makes your Mac display a clock with your chosen

animation.

If you’d like the screensaver to kick in on demand—handy

when you’re messing around online and the boss walks in—you can set a

hot corner

that lets you invoke the screensaver

right away. Click the Hot Corners button and you’ll get a new window

with options for every corner. Use the drop-down menus to set options

for any corner you want. After that, when you move your mouse to that

corner, your Mac fires up the screensaver (or does what you told it

to—put the display to sleep, launch Mission Control, or whatever). The

only downside of setting hot corners is that Apple gives you eight

options for each corner, so unless you want to use a modifier key with

the corner, you don’t have enough corners to use all the

options.

By using modifier keys (you can choose from Shift, ⌘,

Option, and Control), you can get a single corner to do many different

things. To add a modifier key to a hot corner, hold down the modifier

key while you select what you want the hot corner to do from the

Active Screen Corners window’s menus. Using modifiers with hot corners

not only gives you extra flexibility, but it also prevents you from

accidentally invoking the hot corner action when you’re mousing

around.

There aren’t a lot of options in the Dock preference pane,

but they give you control over the most important aspects of the Dock.

You can change its size—from illegibly small to ridiculously large—with

the aptly named Size slider, which works in real time so you can see the

change as you’re making it.

If you turn on Magnification, the application or document you’re

mousing over will become larger than the rest of the items in your Dock.

How much larger? Use the Magnification slider to determine that.

If you want to move the Dock somewhere else, click one of the

three “Position on screen” radio buttons: Left, Bottom, or Right. (Top

isn’t an option because you don’t want the Dock to compete with the menu

bar.)

The “Minimize windows using” menu lets you choose which

animation your Mac uses when you minimize a window: the Genie or Scale

effect. (These days, this is just a matter of personal preference, but

in the early days of OS X, some machines weren’t fast enough to render

the Genie effect.) The “Double-click a window’s title bar to minimize”

checkbox does just what you’d think—with this setting turned on, you can

minimize windows by double-clicking their title bars.

The “Minimize windows into application icon” setting determines

where your windows go when you click the yellow button found at the

upper left of almost every window. If you leave this unchecked, then

minimized windows appear on the right side of the Dock (or at the bottom

of it if you put the Dock on the left or right side of your screen). If

you turn on this checkbox, you’ll save space in the Dock, but to restore

minimized application windows, you’ll have to right-click or

Control-click the appropriate application’s icon in the Dock, select the

minimized window from the application’s window menu, or invoke Mission

Control.

The checkbox labeled “Animate opening applications” sounds

like more fun than it actually is. All it does is control whether

applications’ Dock icons bounce when you launch them. If you turn this

option off, you’ll still be able to tell when an application is starting

because the dot that appears under it (or next to it, if the Dock is

positioned on the left or right) will pulse (unless you’ve turned off

the indicator lights, as explained in a sec). If you turn on

“Automatically hide and show the Dock,” it will remain hidden until you

move the mouse above or next to it.

The blue dots in the Dock that indicate that an

application is running really bother some people. If these dots are the

bane of your existence, unchecking the “Show indicator lights for open

applications” box to make them go away. To figure out which apps are

running once you’ve banished the dots, use Mission Control or the

Application Switcher.

This pane allows you to adjust how you invoke Mission

Control and what happens when you do.

You’ll find an option to display Dashboard as a desktop space,

which is turned on by default; this setting puts a mini-sized Dashboard

screen at the top of your monitor with your other spaces. You can opt to

have OS X arrange your spaces so that the ones you’ve used most recently

are at the top of the list; if you like to manually set your spaces,

uncheck this option. You can also have OS X switch you to a space with

an open window when you switch applications. With this option on (which

it is by default), if you have a space with a Safari window open, say,

and you switch to Safari from another space or full-screen application,

the space you switch to will have a Safari window open already. If you

turn this option off, you might find yourself in a space without an open

window for the application you just switched to, which can be confusing.

The final option, which is on by default, tells Mission Control whether

to group windows by application. Leaving this box checked keeps all the

windows for Safari (for example) together when you invoke Mission

Control.

You also get to change the shortcuts for invoking Mission Control,

opening application windows, showing the desktop, and showing the

Dashboard. Finally, the Hot Corners button lets you define what your Mac

does when you slide your cursor to a corner of the screen (everything

from launching Mission Control to putting your display to

sleep).

The Language tab of the Language & Text preference

pane lets you set the language your Mac uses.

The Text tab is helpful if you spend much time typing. It

includes a list of symbol and text substitutions your Mac performs,

which lets you do things like type(r)and have it automatically show up as ®.

Even better, you can add your

own

substitutions.

Click the + button below the list to add whatever text you want

substituted and what you want it replaced with; make sure the checkbox

to its left is turned on, and your Mac should make that fix

automatically from then on. This won’t work in every application, but in

the supported ones, text substitutions can save you a lot of

effort.

The Text tab also lets you adjust how OS X checks spelling

(the default is automatic by language, but you can have it check

everything for French even if your Mac is using English). The Word Break

setting affects how words are selected when you double-click on a word,

and two drop-down menus let you customize how double and single quotes

are formatted.

The Region tab (which, before Mountain Lion, was called

the Format tab) lets you control the format of the date, time, and

numbers on your machine; pick which currency symbol to use; and choose

between US (imperial) and metric units of measurement.

On the Input Sources tab, the “Input source” list lets you

select the language you want to type in. You can choose anything from

Afghan Dari to Welsh, which can mean a lot of scrolling. To speed things

up, use the search box below the list to find the language you are

after. You can choose as many languages as you like and switch among

them using the flag menu extra that appears in your menu bar

automatically when you select multiple languages. So you don’t have to

spend all day changing languages, you can assign the languages globally

or locally, respectively, using the radio buttons labeled “Use the same

one in all documents” and “Allow a different one for each

document.”

Turning on “Show Input menu in menu bar” adds a multicolor flag to

the otherwise grayscale menu bar. If you check the box labeled Keyboard

& Character Viewer (at the top of the list of input sources), you’ll

be able to launch the Character Viewer and Keyboard Viewer from the menu

bar.