OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide (10 page)

Read OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide Online

Authors: Chris Seibold

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Operating Systems / Macintosh

It doesn’t matter whether you’ve got a relatively tiny

SSD drive in a MacBook Air or 4 terabytes of hard disk space in a

fully tricked-out Mac Pro. Sooner or later, you’re going to want to

get rid of some files, either because your drive(s) are feeling

cramped or you just don’t want the data around anymore. That’s where

the Trash comes in.

The Trash is located on the right end of the Dock (or, if you’ve

moved the Dock to the left or right of your screen, it’s on the

bottom; see

Dock

to learn how to relocate the

Dock). To banish files from your Mac, select them and then drag them

from the Finder to the Trash (or press ⌘-Delete).

When the Trash has something in it (whether it’s one item or a

million), its icon changes from an empty mesh trash can to one stuffed

with paper. This lets you know that the files you’ve moved to the

Trash are still there, and that you can retrieve them (until you empty

the Trash).

To open the Trash and view its contents in a Finder window,

click its Dock icon. (You can view the items in the Trash with the

Finder, but you can’t actually open a file that’s in the Trash;

attempting to do so will result in an error message.) If you find

something in the Trash that shouldn’t be there, you can either drag it

out of the Trash or select it and then click File

→

Put Back to send it back to where it was

originally.

To

permanently

delete items in the Trash,

right-click or Control-click the Trash’s Dock icon and choose Empty

Trash, or open the Finder and either choose Finder

→

Empty Trash or press Shift-⌘-Delete.

Note that emptying the Trash doesn’t completely remove

all traces of the files you deleted. Those files can be recovered with

third-party drive-recovery utilities, at least until the disk space

they previously occupied has been written over with new data. To make

it harder for people to recover deleted data, in the Finder, choose

Finder

→

Secure Empty Trash.

This command overwrites the deleted files multiple

times.

If you work with a lot of sensitive files, you can tell the

Trash to

always

write over files you delete by

going to the Finder’s preferences (Finder

→

Preferences or ⌘-, while in the Finder) and,

on the Advanced tab, checking the box next to “Empty Trash securely.”

You probably want to leave the “Show warning before emptying the

Trash” option checked because, once you securely empty the Trash,

you’re not getting that data back.

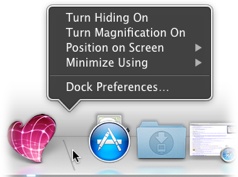

Here are a few quick and easy changes you can make

without invoking the Dock’s preference pane. If you right-click or

Control-click the divider between the two parts of the Dock (it’s a

subtle, dark-gray line), you’ll get the pop-up menu shown in

Figure 3-22

. This menu lets you

choose whether to automatically hide the Dock when you’re not using

it, change the magnification of icons in the Dock, change the Dock’s

location, change the animation OS X uses when you minimize windows,

and open the Dock’s preferences.

Figure 3-22. A quick way to make Dock adjustments

You can change the size of the Dock by dragging up or down over

the dashed divider to increase or decrease the Dock’s size,

respectively.

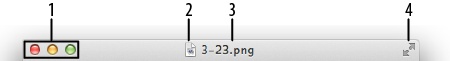

The Dock is the most obvious way to switch among

applications while they’re running, and Mission Control is probably the

niftiest way, but Mountain Lion gives you a third way to flip among open

apps. The aptly named Application Switcher (

Figure 3-23

) lets you switch

applications without taking your hands off the keyboard, a huge

timesaver if you change programs often. To use it, just hit

⌘-Tab.

Figure 3-23. Change apps and keep your fingers on the keyboard

Holding the ⌘ key while repeatedly hitting the Tab key cycles

through the open applications from left to right, and then wraps around

to the first application on the left again (use Shift-Tab instead to go

the opposite direction). Alternatively, you can press ⌘-Tab and then,

while still holding down ⌘, use the

←

and

→

keys to move between applications.

When the application you want to

switch to has a white border around it, release the keys and that

program will come to the front.

Most windows in OS X share some characteristics, shown in

Figure 3-24

. Knowing what

they do will help you be much more productive when using Mountain

Lion.

Figure 3-24. Mountain Lion’s standard window controls, which live on the title

bar

Here’s what these controls do:

The red button closes the window; if you point your

cursor at it, you’ll see an × or—if there are unsaved changes to the

current document—a dark-red dot inside it. The yellow button minimizes

a window; put your cursor over this dot, and you see a −. The green

button maximizes the window and displays a + when you point to

it.This is called the proxy icon. Drag it to create an

alias of the current file, or Option-drag it to copy the current

file.The name of the current file.

If the application you’re using can go full screen, you’ll see

these arrows. See the section

Full-Screen Applications

for details.

The following table lists some keyboard

shortcuts that are useful for working with windows.

Action | Key |

|---|---|

Open a new window | ⌘-N |

Close the active | ⌘-W |

Minimize the active | ⌘-M |

Minimize all windows for | Option-⌘-M |

Not every key combination is universal. For example, some

applications use ⌘-M for something other than minimizing the active

window.

If the green maximize button isn’t convenient for you, you

can manually resize windows in Mountain Lion. To pull this trick off,

put your cursor over the edge of a window and, when the cursor changes

to a double-headed arrow, simply drag to resize the window.

You’ll still see the occasional triple-slash resizing handle in

the lower-right corner of programs such as Microsoft Word. Don’t

worry, you can still resize such program windows by dragging any edge,

though the resize handle works, too.

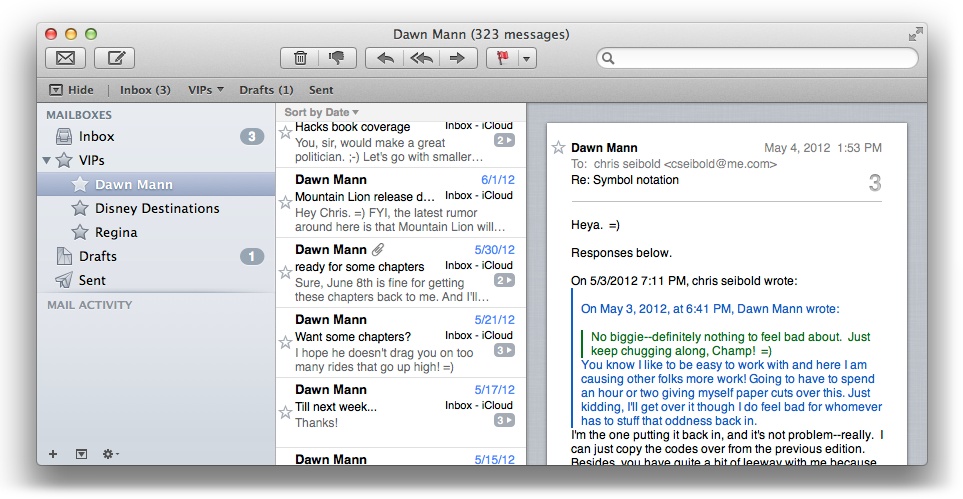

Ever longed for a more immersive Web-browsing experience, or

wished that iCal would take over every pixel of screen space? Having

Safari fill your screen when you’re reading a longish Wikipedia entry is

great, and working in Preview using the full screen lets you see more of

the image you’re tweaking.

Not every application has a Full Screen mode, but it’s easy to

figure out which ones can suck up all your screen real estate: look for

the double arrows in the upper-right corner of the program’s window (

Figure 3-25

).

Figure 3-25. Mail is one of many Full Screen–capable apps in Mountain

Lion

Once the application is in Full Screen mode, you can do whatever you

wish, free from the distractions of your desktop and other programs. When

you’re using that application, move your cursor to the top of the screen

and the menu bar will reappear. Click the blue arrows on the right end of

the menu bar to return the program to a regular window.

You may be thinking that full-screen applications

seem

like a great idea but that they might be a

little too much work when you need to use another program or get back to

the desktop. Don’t worry, there are plenty of easy ways to get out of a

full-screen application. You can switch programs with the ⌘-Tab key combo,

hit the Esc key to exit Full Screen mode, or invoke

Mission Control

.

If you use multiple monitors, you might be hoping for a world

where you can run one application in Full Screen mode while doing

something else on the other monitor. Sadly, you’re out of luck:

launching a full-screen application in Mountain Lion renders the second

monitor useless—unless your goal is to look at a static, gray-linen

screen.

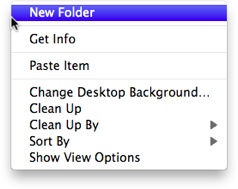

As you already know, folders are where you keep files. But

OS X also includes two special kinds

of folders: Burn folders and Smart folders. This section explains ’em

all.

Your Mac comes preloaded with some folders that are appropriate

for commonly saved files (documents, pictures, music, and so on), but

you’ll also want to make your own folders. For example, you might make a

subfolder for spreadsheets within the Documents folder, or put a folder

on your desktop where you can toss files that end up scattered around

the desktop. To create a regular folder in the Finder, either choose

File

→

New Folder (Shift-⌘-N), or

right-click or Control-click a blank spot in a folder and then choose

New Folder from the Context menu shown in

Figure 3-26

. You can also

right-click or Control-click the desktop and then choose New Folder to

add a folder there.

Figure 3-26. Creating a new folder via the Context menu

OS X names new folders “untitled folder,” and it iterates

this name if you create a series of folders without renaming them after

you create each one, so you end up with “untitled folder,” “untitled

folder 2,” “untitled folder 3,” and so on. To change a folder’s name,

click the folder once and then press Return or click the folder’s

current name. The area surrounding the name gets highlighted so you can

type a new one. When you’re done, hit Return to make the new name

stick.

Creating a Burn folder is the easiest way to get files or

folders from your Mac onto an optical disk (a CD or DVD). To do so, go

to the Finder and select File

→

New Burn

Folder; a new folder with a radiation symbol on it will appear in the

current folder. (If you’ve made filename extensions visible—see

Finder preferences

—you’ll notice that folder’s suffix is

.fpbf

.) Be sure to give this folder

a descriptive name like

discoinferno

. Then you can

start tossing any files you want burned onto a disk into that

folder.

The files aren’t actually being moved to the Burn folder;

Mountain Lion is just creating aliases that point to them; when the time

comes to burn the data, OS X will burn the original file(s). Since the

files are aliased, if you decide to get rid of the Burn folder without

burning the data, you can simply toss the folder into the Trash. The

original items will remain untouched.

Once you’re ready to burn the data, open the Burn folder and click

the Burn button in its upper-right corner. Insert a disk when prompted,

and Mountain Lion takes care of the rest.

There are Smart folders all over your Mac: in iTunes,

Mail, and lots of other places. Smart folders are actually Spotlight

search results, but you can browse them just like regular

folders.

To create your own Smart folders, head to the Finder and choose

File

→

New Smart Folder or press

Option-⌘-N. In the search box of the new window that appears, type in

text describing what you want to find, and Mountain Lion will fill the

folder with items that meet your criteria. As you type, Mountain Lion

displays suggestions for refining your search. Say you want an easy way

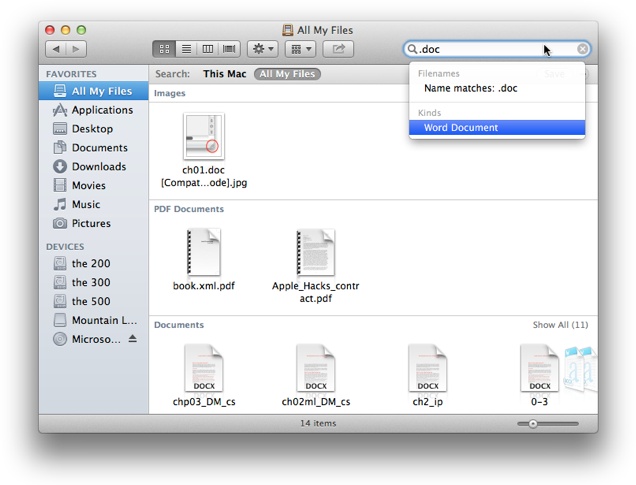

to manage all your Word files. Start typing.docin the search box, and

Mountain Lion will make handy suggestions like the ones shown in

Figure 3-27

. Select “Word

Document” under Kinds and all your Word documents will appear in the

Smart folder.

Figure 3-27. OS X knows what you’re looking for!

If the results aren’t quite what you want, you can further

refine your search by clicking the gear icon in the window’s toolbar and

selecting Show Search Criteria. Doing so will let you refine your search

by adding more conditions for a match. (Love the search you created?

Click Save and the search will be available to you anytime you need

it.)

There are more great things about Smart folders. The results of

your search don’t change where anything is actually stored on your Mac,

but you can act as if all the files reside in the Smart folder. That

means that, even though the files in it could be scattered across a

hundred folders on your Mac, you can move, copy, and delete them just as

if they all resided in the Smart folder. (If you delete a file from a

Smart folder, you’ll also delete that file from your Mac.)

Don’t worry about your Smart folders slowing down your Mac or not

displaying changes immediately. Smart folders are constantly updated, so

when you add a new file that fits the Smart folder’s criteria, the file

shows up in the Smart folder right away.