Poison (6 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

CHAPTER 3

“YOU KILLED MY DAUGHTER”

April 5, 1995

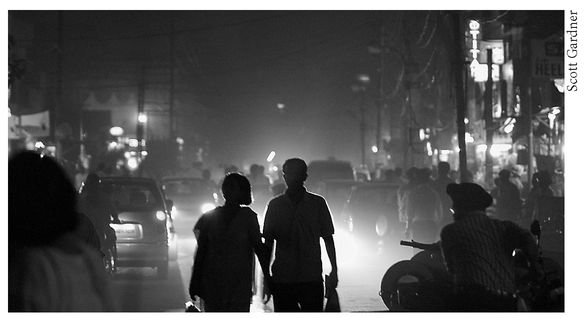

Ludhiana, India

Ludhiana, India

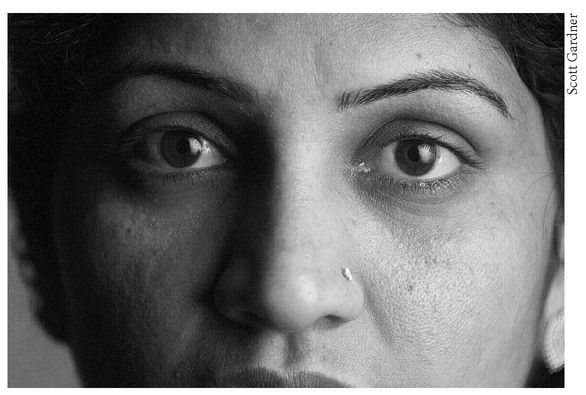

Sarabjit Kaur Brar had tanned, smooth skin; her voice was soft and hesitant. She usually managed to keep her smile at bay, but it would occasionally crack and briefly light up a room. In English her name meant “the universe.” She sat on the edge of the bed, the moment nearing when her new husband, a man she neither knew nor loved, would arrive and expect intercourse from her. His name was Sukhwinder Dhillon. He was 36 years old, had two young daughters. She was 20, and had never even kissed a man before. Sarabjit waited to hear him mount the stairs and enter the room. She sat there, her small hands clasped on her lap as though in prayer, head bowed, staring at her bare feet, wearing a magenta lehnga—a formal silk blouse and skirt—and sheer chunni wrapped regally around her neck. Traditional bridal bracelets colored ivory, maroon, and gold lined the new bride’s thin wrists and forearms. The ritual red dye that covered the palms of her hands in an intricate pattern looked like dried blood.

Sarabjit Kaur Brar

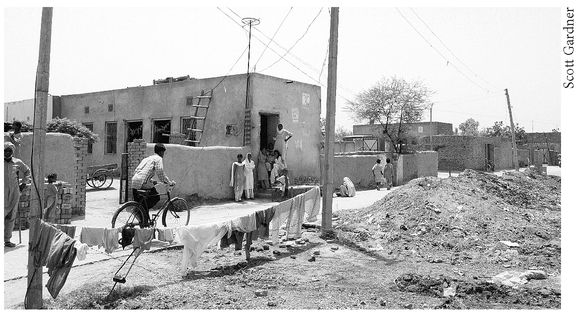

She lived in a farm village called Panj Grain, two hours southwest of Ludhiana, where 2,000 people lived in a collection of bungalows made of a combination of concrete and sun-hardened mud and cow dung. The road to her arranged marriage had begun two weeks earlier when Sarabjit had first been presented to Dhillon. She had sat in the living room of her uncle Iqbal’s home along with her parents. Sarabjit wore a blouse known as a salwar kameez, rose-colored pants, and her head was covered in a scarf.

Panj Grain, the village Sarabjit called home.

Iqbal had suggested his niece to Dhillon as a prospective bride. And now, to her uncle and others, the bride-to-be seemed happy. Why wouldn’t she be? Marrying a Canadian citizen like Dhillon meant she could move to Canada, a new life, new opportunity. It was the dream of many Punjabis. Not all young women like Sarabjit held such an arrangement as their life mission, but what did the wishes of an Indian girl matter? To even hope to marry a man of your choice would mean exercising an independence that in the arranged-marriage culture was unacceptable. Sarabjit would marry whomever her parents deemed appropriate. “Love” marriages, as Indians called them, were more common in liberal circles in the big cities, but arranged marriages were still the overwhelming majority. Even in Canada, Sikh girls who left India as toddlers felt the pressure of their culture. Rebelling against an arranged marriage in Punjab, for a girl like Sarabjit from a traditional village family,

was not even a remote possibility. It would mean disgracing the entire family in the eyes of the community, perhaps even bringing death upon herself.

was not even a remote possibility. It would mean disgracing the entire family in the eyes of the community, perhaps even bringing death upon herself.

Sarabjit averted her brown eyes from Dhillon’s stare. Everyone seemed to call Dhillon by his nickname,

Jodha

, which means brave warrior. Sarabjit heard him speak in his rough Punjabi. The man was clearly uneducated, she could tell immediately.

Jodha

, which means brave warrior. Sarabjit heard him speak in his rough Punjabi. The man was clearly uneducated, she could tell immediately.

“I’m bringing a hundred friends to the wedding,” Dhillon declared in his rapid-fire cadence. “Look after them properly.” He said not one word to Sarabjit. She felt angry, claustrophobic. It was all closing in on her, out of her control. She locked her mother’s eyes in a cold stare. At the wedding, she saw the looks on the faces of her friends. They felt sorry for her, even though they knew their number would be up one day, too. Hopefully their parents would arrange marriages to more appealing men. Sarabjit’s closest friend, Pinky, leaned over and whispered, “Sarabey, what have you gotten yourself into? It’s all right. Everything’s going to be fine.”

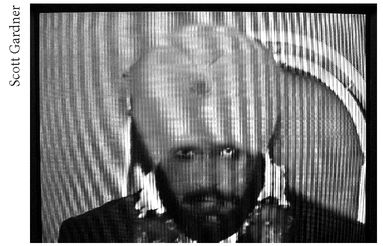

Dhillon on his wedding video

Wedding guests paraded past Dhillon as he sat with Sarabjit. They handed him cash and jewels. Dhillon had told Sarabjit’s family to sweeten the dowry, and handed her parents, Gurjant and Ranjit, a wish list. He requested rings for his brother and father—even though Dhillon’s father had long been dead. Dowry is a serious business in India. When the dowry is found wanting by the groom or in-laws, the new bride is on occasion burned alive. “Dowry deaths” the local newspapers call them. The dowry paid to Dhillon included the rings, three bracelets, including a gold one for his mother, a neck chain, clothes. Dhillon told the parents he didn’t want stuff like a TV, fridge, or the family’s prized motorcycle. He could get those things in Canada. He preferred cash. The dowry he received totaled two Indian lakhs, or

200,000 rupees—about $9,000 Canadian. To Dhillon, the amount was modest; he could earn that much in Canada selling one used car. But for Sarabjit’s family, who owned a house and a patch of farmland, it was a massive expense; two lakhs is a small fortune in India. They borrowed money and, to help pay Dhillon, Sarabjit’s grandfather sold half of his farm and the family tractor. The family considered it an investment. They mortgage their lives to Dhillon, give him their daughter, and the payoff would be a move to Canada for all of them in the future through family reunification. The golden dream.

200,000 rupees—about $9,000 Canadian. To Dhillon, the amount was modest; he could earn that much in Canada selling one used car. But for Sarabjit’s family, who owned a house and a patch of farmland, it was a massive expense; two lakhs is a small fortune in India. They borrowed money and, to help pay Dhillon, Sarabjit’s grandfather sold half of his farm and the family tractor. The family considered it an investment. They mortgage their lives to Dhillon, give him their daughter, and the payoff would be a move to Canada for all of them in the future through family reunification. The golden dream.

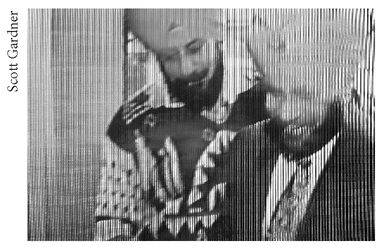

Dhillon had taken his two young daughters, Aman and Harpreet—still grieving the loss of their mother—out of school in Hamilton to India for the wedding. At the wedding he was also accompanied by his friend, a man named Manjit Singh Sidhu, a hulking inspector with the Punjab state police who went by the nickname

Dulla

(pronounced doo-la), which meant “the groom” in English. Dulla always carried a revolver sticking out of his waistband for all to see. After the wedding, the families returned to the bride’s home in Panj Grain to pick up Sarabjit’s belongings. As Sarabjit got into the car with Dhillon to drive the two hours to his family home in Ludhiana, Dulla pulled the gun and fired several celebratory shots into the air.

Dulla

(pronounced doo-la), which meant “the groom” in English. Dulla always carried a revolver sticking out of his waistband for all to see. After the wedding, the families returned to the bride’s home in Panj Grain to pick up Sarabjit’s belongings. As Sarabjit got into the car with Dhillon to drive the two hours to his family home in Ludhiana, Dulla pulled the gun and fired several celebratory shots into the air.

Dhillon and friend “Dulla” in wedding video

In the middle of Ludhiana was Dhillon’s neighborhood, called Birk Barsal. The change for Sarabjit was like a slap in the face. Panj Grain consisted of taupe bungalows surrounded by green fields, a farm village where at midday the loudest sound was a

water pump filling the rice paddies. Birk Barsal buzzed within the city’s overheated old industrial core, a mess of impossibly narrow streets and wires overhead, gray-walled textile factories clacking and shucking, horns and bells from rickshaws, scooters, bicycles, trucks and cars squeezing past one another loaded with wool, and other goods. Shops and markets spilled onto the street, diesel exhaust filling the air along with the smell of sweat and fruit and vegetables decaying in the heat.

water pump filling the rice paddies. Birk Barsal buzzed within the city’s overheated old industrial core, a mess of impossibly narrow streets and wires overhead, gray-walled textile factories clacking and shucking, horns and bells from rickshaws, scooters, bicycles, trucks and cars squeezing past one another loaded with wool, and other goods. Shops and markets spilled onto the street, diesel exhaust filling the air along with the smell of sweat and fruit and vegetables decaying in the heat.

Ludhiana at night

The white Maruti turned left off the main street, up a narrow alley, past a woolen goods store and a noisy textile shop, and stopped in front of Dhillon’s walk-up apartment. Sarabjit’s bracelets jangled as she scaled the steps. That night, her wedding night, sitting on Dhillon’s bed, Sarabjit had never felt more alone, afraid or trapped. She tried to block out her fear. What was the point of letting doubts creep in? Do not resist. It is pointless, only brings more pain. But subversive thoughts danced in and out of her mind anyway. She knew the entire concept was so Western, but what of her dreams? She grew up in a village called Mairu, even smaller than Panj Grain, with three younger brothers. She completed high school then moved to Panj Grain at 19. She was still in the first year of college, studying Punjabi and history, trying not to dream of a future of her own design, but somewhere inside, in a perfect world, she had wanted to be a teacher. She always knew it would never come true.

Other books

Redeeming Heart by Pat Simmons

Nano Contestant - Episode 1: Whatever It Takes by Leif Sterling

Murder With Reservations by Elaine Viets

Kept by Him by Red Garnier

A Journal of Sin by Darryl Donaghue

The Too-Clever Fox by Bardugo, Leigh

Grace Alive: a Christian Romance by Natasha House

The Bride Box by Michael Pearce

Sins of Innocence by Jean Stone

The Blood Debt by Sean Williams