The Birth Order Book (13 page)

Read The Birth Order Book Online

Authors: Kevin Leman

Tags: #Christian Books & Bibles, #Christian Living, #Family, #Self Help, #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Psychology & Counseling, #Personality, #Parenting & Relationships, #Family Relationships, #Siblings, #Parenting, #Religion & Spirituality, #Self-Help, #Personal Transformation, #Relationships, #Marriage, #Counseling & Psychology

____ 8. You find yourself apologizing for something because you could have done it better if you’d had more time.

____ 9. When in a meeting, working in a team, or in any group situation in the workplace, you prefer to be in control of what’s happening.

____ 10. Realizing your deep need to have all your ducks in a row, you insist that those around you have their ducks in the same row (i.e., think exactly the way you do).

____ 11. You tend to see the glass half-empty instead of half-full.

Scoring:

0–22: Why are you reading this chapter anyway? You’re certainly not even close to being a perfectionist.

23–27: mild perfectionist

28–36: medium perfectionist

37–44: extreme perfectionist (you’re too hard on yourself and everyone else)

A True Perfectionist at 18 Months

We all develop our particular lifestyle (the way we act, think, and feel) when we are very young, and that includes perfectionists. Sande and I saw the handwriting on the wall with our oldest daughter, Holly, when she was only 18 months old. We were on an R & R trip to California and the seashore, and it was the first time on any beach for Holly. She soon discovered sand and came toddling over, holding up one finger with three or four grains of sand stuck to it.

“Ugh, ugh,” she grunted, very displeased with all this “mess” and wondering if there wasn’t something we could do about it. Before our eyes—at the tender age of 18 months— Holly was displaying signs of the true perfectionist. Despite our best efforts to encourage and reinforce Holly rather than find fault or pick flaws, she has grown into a mature woman who seeks perfection in all she does. And that’s why, as I mentioned earlier, her high school literature students get detention when they come to class unprepared. Holly knows she would have had her assignments in on time (she always did in high school and in four years of college), so she wants her students to do the same.

But while Holly is far from being a slob, she is hardly the neatest one in the family. That honor goes to her sister Krissy, our secondborn middle child (more about her in chapter 8). But I don’t find it odd at all that our perfectionist, firstborn daughter acts a bit out of character and isn’t always concerned about having a perfectly neat room. It’s her own way of covering her frustration with life’s less-than-perfect warts and bumps.

People who score in the medium-to-extreme perfectionist range on the quiz usually fall into the category I call “discouraged perfectionists.” They go through life telling themselves the lie “I count only when I’m perfect.” It becomes their lifestyle. I’m not talking about lifestyle in the sense of what you wear, drive, eat, or drink.

Lifestyle

is a term coined by Dr. Alfred Adler, who used it to refer to how people function psychologically to reach their goals (more on this in chapter 12).

Beware the Ultracritical Perfectionist

When the discouraged perfectionist reaches a certain point, she can become ultracritical not only of herself but of others. The person in the want ad, for example, may somehow find a man who happens to meet all her “requirements” and is foolish enough to marry her. But after the honeymoon is over, he will almost certainly find he has an ultracritical discouraged perfectionist on his hands, and he will pay a big price.

Ultracritical discouraged perfectionists hide behind a mask of “being objective.” Their favorite motto is: “The good is the enemy of the best!” They are such flaw pickers that they can become a constant irritant to everyone. They can even become toxic, making fellow workers so angry or so worried about their performance that they can’t do a job properly or safely.

Realize you can never please this ultracritical perfectionist because he cannot please himself.

I always tell managers and executives that if they have a severely discouraged ultracritical perfectionist on the payroll and he or she is working directly with other people, they should consider strong measures. First, this severely discouraged perfectionist needs a friendly warning and a chance to modify his or her behavior. If the extreme perfectionism continues, the best option is to transfer this person to another area—preferably where he or she can work mostly alone. And if that isn’t possible, perhaps this ultracritical perfectionist should be advised to look for another line of work.

Speaking of looking for another line of work, if you are serving under an extremely critical perfectionist who happens to be the office manager, the president, the owner of the company, or some other position of tremendous power, do not get down on yourself because of the constant criticism. Instead, realize you can never please this ultracritical perfectionist because he cannot please himself. Perhaps the job pays so well that you can hang on and be hammered with the negatives while getting very little positive reinforcement. On the other hand, if self-fulfillment and job satisfaction are really important, it’s best to consider moving on.

For the perfectionist, nothing is ever good enough, and he or she is never quite finished with the task.

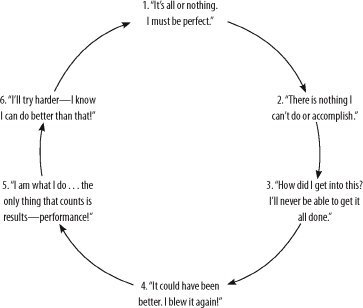

The Cycle of Perfectionism

For the perfectionist, nothing is ever good enough, and he or she is never quite finished with the task. The cycle of perfectionism generally follows these steps:

1. The perfectionist is the originator of the motto “It’s all or nothing.” He is sure he must be perfect in everything he does. He tends to be a streak performer; when he’s hot, he’s hot, and when he’s not, he’s a mess.

2. This leads to biting off more than he can chew, perhaps the perfectionist’s major problem. As a perfectionist, he can always take on one more thing, even when his schedule is absolutely full and running over. This leads toward the next step in spiraling downward to defeat.

3. The hurdle effect causes the perfectionist to panic. He looks down the track and sees all those hurdles ahead, and each hurdle gets a little higher than the last one. The hurdles aren’t necessarily there, but they are perceived obstacles, and they are overwhelming.

How did I get into this mess? How am I ever going to get out?

are the typical laments of the perfectionist.

4. As the hurdles seem to grow taller and taller, the perfectionist compounds his problems by maximizing failures and minimizing successes. If a perfectionist makes mistakes, he internalizes them, chews on them, and goes over and over in his mind what went wrong. If he manages to do something right, he thinks,

It could have been better.

5. When the pressure becomes too great, the perfectionist may bail out, quitting the project or turning it in less than well done with the excuse, “There just wasn’t enough time.”

6. Whether the perfectionist manages to finish his job or backs out of it because it simply proved too much, he is always left feeling he must try harder. He is the original victim of what I call the “Avis complex.” For years, Avis has willingly placed themselves in a secondary position to Hertz. The Avis motto? “Yeah, we’re in second place, but

we try harder

.” To me, those words sum up the quandary of the perfectionist: sure that he’s number two (or lower), he’s never satisfied and always shooting to be better.

The Avis complex doesn’t haunt only “average” people. It can be the bane of the celebrity, the highly successful executive, or the genius.

Actor Alec Guinness admitted he was very insecure about his work and added, “I’ve never done anything I couldn’t pull to bits.”

Abraham Lincoln presented his Gettysburg Address and then described it as “a flat failure.”

Leonardo da Vinci, who was an outstanding painter, sculptor, scientist, engineer, and inventor—actually, one of the world’s true geniuses—said, “I have offended God and mankind because my work didn’t reach the quality it should have.”

1

Figure 1

The Hopeless Pursuit of Perfection

2

Skilled Procrastinators

This six-step cycle (see diagram above) can be repeated several times a day, depending on what the perfectionist is doing. While going through this cycle, the perfectionist often slips into the habit of procrastinating.

Have you ever known a real procrastinator? (Perhaps you know one all too well.) The procrastinator has a real problem with time, schedules, and deadlines. A major reason behind the procrastination is the perfectionistic fear of failure. The procrastinating perfectionist has such high expectations that he or she is afraid to start a project. He or she would rather stall and rush to get something done at the last minute. Then the procrastinator can say, “If there had been more time, I could have done a much better job.”

Recently I did an entire radio show on the topic of perfectionism and feeling that you are not good enough, cannot jump high enough, and can never do anything really well. We had many callers that day who struggle with perfectionism, procrastinating, and just feeling like they don’t measure up in life. One of them was Michael, who complained that he never got things accomplished and never finished things (a sure sign of a procrastinating perfectionist). He started projects with his wife or his kids and didn’t finish them. He felt overcommitted and admitted he had definitely been biting off more than he could chew.

Michael sounded like the very person I had in mind when I wrote

When Your Best Isn’t Good Enough

,

3

a book that zeros in on perfectionism and how to conquer it. While we were on the air, I told Michael I could describe him and his family without ever seeing any of them. I said:

Sometimes you’ll be asked to do something and you’ll say no because you’ll look at the big picture and say,

This is impossible, I can’t do it.

And then you’ll move on to something else. Or, as you’ve already admitted, you will do some things to a certain degree or a certain point and either lose interest or turn left or right at the last minute.

My big guess is that you grew up in a home where criticism reigned. In other words, you had a critical-eyed parent, so you protected yourself from criticism by not finishing things. Your thinking was,

If I don’t finish it, how can anyone criticize me?

This, of course, is where self-deception comes in and we become great at lying to ourselves.

Michael replied, “That’s almost exactly who I am and what I do. Some days I’ll look at the problem and think,

You know, this has eight or nine steps. I can’t do this.

Or some days I’ll even do two or three steps and then, as you said, turn right or turn left and just walk away from the problem. And that’s one of the biggest issues I have—that walking away. I need to stop and say, ‘I’ve committed to this. This is something that needs to get done.’”

As is so often the case, Michael knew the answer to his problem. It was simply a matter of following through and changing his behavior. I asked him if he had liked building models as a kid, and he said that indeed he did—“model cars, stuff like that.” I told Michael I found that guys who really struggle with procrastinating and perfectionism usually loved building models or assembling puzzles—anything where all the parts come together.

“Here’s the kicker,” I added. “You’re a very competent person, more competent than you’ve ever believed yourself to be. If I talked to people who know you well, I believe they would say, ‘He’s a guy with such great potential. It’s unbelievable!’”

It turned out Michael was production manager of a ceramics shop—a very exacting kind of work that is a natural for a perfectionist. I said I was quite sure that people had told him he had done beautiful work on certain ceramic pieces, but inside he was saying,

If you only knew about that little flaw . . .

“Very, very true,” Michael answered. “You know, I recycle a lot of ceramics because of that.”

What did Michael need most of all? The permission to be imperfect! I urged him to flaunt his imperfections before his children and to be the first to say to them or to his wife, “Honey, I’m sorry. I was wrong. I shouldn’t have said that.”

As for getting things done, Michael needed to set some time limits for finishing projects. He had to make the limits reasonable, but at the end of the time stop and accept the job the way it was without trying to perfect it.

So many people who struggle with perfectionism will say things such as, “It’s no good,” or “Oh, it isn’t much—it’s really nothing.” Those are sure signs of a perfectionist who is fending off criticism. I urged Michael not to be so quick to put himself down. Instead, he needs to start telling himself the truth—that he has really been given a wonderful gift and needs to use that gift in the most positive way he can.