Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (32 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

4.

Ask about current treatment (e.g. diet, pancreatic supplements, vitamin supplements, cholestyramine, antibiotics).

5.

Enquire about family history (e.g. coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease).

6.

Ask about social problems related to the chronic illness.

The examination

Pay particular attention to the current weight and nutritional status (e.g. BMI), the presence of abdominal scars, skin lesions (e.g. bruising, dermatitis herpetiformis (

Fig 7.1

), pigmentation (

Fig. 7.2

), erythema nodosum (

Fig 7.5

), pyoderma gangrenosum (

Fig 7.4

), stomatitis, perianal lesions), signs of anaemia, signs of chronic liver disease, signs of peripheral neuropathy and lymphadenopathy.

FIGURE 7.2

Whipple’s disease and skin pigmentation. Erythema nodosum-like subcutaneous, slightly erythematous nodules affected (a) the lower legs and (b) the abdomen. J Schaller. Erythema nodosum-like lesions in treated Whipple’s disease: Signs of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology

, 2008. 60(2):277–288, with permission.

FIGURE 7.3

Aphthous ulcers. S O Akintoye, M S Greenberg. Oral soft tissue lesions: Recurrent aphthous stomatitis.

Dental clinics of North America

. 2005. 49(1):31–47, Fig 2, 2005.

FIGURE 7.4

Pyoderma gangrenosum. E Wierzbicka-Hainaut et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum récidivant lors des grossesses. Recurring pyoderma gangrenosum in pregnancy.

Anales de dermatologie et de venereologie

. 2010. 137(3):225–9, Fig 1.

FIGURE 7.5

Erythema nodosum. J Mana, J Marcoval. Erythema nodosum.

Clinics in dermatology

. 2007. 25(3):288–94. Elsevier, with permission.

Investigations (see

Table 7.2

)

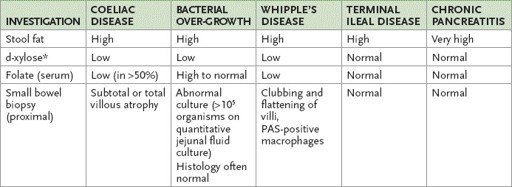

Table 7.2

Typical results of investigations in malabsorption

*

This is a test of proximal small bowel function. Falsely low values occur in patients with chronic kidney disease, dehydration, ascites or hyperthyroidism and in the elderly. PAS = periodic acid-Schiff technique.

1.

Demonstrate malabsorption:

a.

the ‘big six’ laboratory screen tests

– look for a low serum iron, prolonged prothrombin time, low calcium, low cholesterol, low carotene and a positive Sudan stain of the stool for fat (which is a good screening test for steatorrhoea)

b.

faecal fat estimation over 3 days

– more than 7 g per day is abnormal; note that patients with severe small bowel diarrhoea of any cause without fat malabsorption may lose up to 14 g per day; this gold standard test is very useful if you strongly suspect fat malabsorption based on the screening evaluation, but is not widely used or available

c.

glucose or lactulose breath hydrogen test

for bacterial overgrowth (think about this possibility in the setting of macrocytosis with a high folate and low B

12

level, or in patients with structural, motility or immunoglobulin deficiency disorders that predispose to bacterial overgrowth)

d.

Schilling test

for ileal disease causing vitamin B

12

deficiency (rarely ordered)

e.

SeHCAT test

for bile salt malabsorption that can occur with ileal rejection or terminal ileal disease (e.g. Crohn’s disease).

2.

Evaluate the consequences:

a.

blood count with particular attention to red cell indices

b.

serum iron and ferritin, serum and red cell folate, and vitamin B

12

studies

c.

serum albumin estimation

d.

vitamin D level (25-OH vitamin D), serum calcium, phosphate and alkaline phosphatase estimations

e.

clotting profile – international normalised ratio (INR)

f.

cholesterol and carotene.

3.

Find the cause.

a.

Check small bowel X-ray films for localised disease (e.g. Crohn’s disease or anatomical causes of bacterial overgrowth such as diverticula or blind loops).

b.

Check gastroscopy and small bowel biopsy (the optimal number for diagnosis of coeliac disease is four duodenal biopsies, as disease can be patchy) and duodenal aspirate for histology, parasites and bacterial overgrowth; look for multiple duodenal ulcers (e.g. as a result of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, lymphoma, jejunoileitis).

Subtotal villous atrophy may be present histologically in:

•

coeliac disease

•

tropical sprue

•

giardiasis

•

lymphoma

•

hypogammaglobulinaemia

•

Whipple’s disease.

Note that tissue transglutaminase (or anti-endomysial antibody) is the most useful screening test for sprue. Remember that 2% of the population is IgA deficient and will have negative serology, so check IgA levels if testing is negative and your suspicion is high. Do not rely on antigliadin antibodies. Serology is not a substitute for small bowel biopsy, which remains the gold standard test if coeliac disease is suspected.

c.

Vitamin B

12

absorption may be abnormal in ileal disease, bacterial overgrowth, pernicious anaemia and pancreatic disease.

d.

Greatly raised faecal fat levels (>40 g per day) strongly suggest pancreatic disease, but this test is now uncommonly available. An alternative is faecal elastase testing. Suspected pancreatic disease is investigated by plain abdominal X-ray films (for calcification), CT scan, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic ultrasound; pancreatic function testing is not performed routinely.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the cause and also involves the replacement of essential nutrients (see

Table 7.3

).

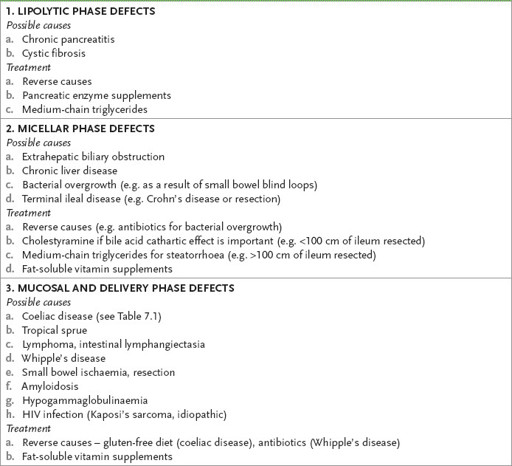

Table 7.3

Causes and treatment of malabsorption

Management of coeliac disease

Coeliac disease is a commonly missed diagnosis! Have a low threshold for ordering serology; patients may present with no gastrointestinal symptoms. Remember to consider the possibility of coeliac disease in a patient with osteoporosis or osteomalacia, abnormal transaminases, new neuropsychiatric symptoms or unexplained iron deficiency.

1.

The management of coeliac disease includes a gluten-free diet (exclusion of wheat, rye and barley; there is controversy about oats). Symptoms usually improve in weeks and the histology in months; tissue transglutaminase antibody also normalises in 3 to 6 months.

2.

A strict diet may reduce complications. It is reasonable to re-biopsy the duodenum in 3 months to confirm histological healing.

3.

Lack of response to a gluten-free diet may be caused by inadvertent gluten exposure, the presence of another problem (e.g. lactose intolerance, pancreatic insufficiency, bacterial overgrowth), refractory sprue (which may respond to corticosteroids) or lymphoma (T cell enteropathy: unresponsive to steroids).

4.

Pneumococcal vaccine is recommended because of the hyposplenism of coeliac disease.

5.

Osteoporosis must be looked for and managed.

6.

Latent coeliac disease can be diagnosed if the small bowel biopsy appears normal but there is a positive serology. For these patients, a gluten-free diet is not usually recommended, but follow-up with repeat biopsy is indicated if the symptoms recur.