Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (34 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

You are more likely to encounter Crohn’s disease in the clinic and exam than UC. A rectal exam for fistula is routine (the results will be provided for you). Small bowel imaging nodalities include CT enteroclysis or MR enteroclysis. Capsule endoscopy is widely available, but remember the capsule may obstruct the small intestine in Crohn’s disease. Fistula can be evaluated by radiology (e.g. CT, MR and fistulography) and examination under anaesthesia. For active colonic disease, treatment is similar to ulcerative colitis. Always advise the patient to stop smoking! Always try to taper off and stop steroids once the patient is in remission. A multi-disciplinary team approach is needed to manage what can be a devastating disease long term.

1.

Sulfasalazine or mesalazine is more effective in colonic disease, whereas steroids are more effective in small bowel disease.

2.

Budenoside (a steroid derivative that acts locally and is 90% inactivated by the liver) is useful in ileocolonic disease.

3.

In quiescent disease, mesalazine only very modestly reduces the frequency of relapse in the postoperative setting.

4.

Azathioprine (or 6-mercaptopurine) is useful for those who cannot cease steroids and to reduce relapse (including post-resection surgery). Methotrexate is an alternative if azathioprine fails.

5.

Oral cyclosporin is largely ineffective.

6.

With extensive ileal disease, diarrhoea may respond to a bile-salt-sequestering drug (cholestyramine or colestipol).

7.

Metronidazole or ciprofloxacin is modestly useful for severe perianal disease and fistulae, which tend to recur once treatment is stopped; azathioprine may be tried in difficult severe cases.

8.

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha monoclonal antibody-infliximab and adalimumab heal fistulae and suppress underlying inflammatory disease, but relapse is common and therefore maintenance treatment is required. A positive antinuclear antibody occurs in half the patients. Infusion reactions, infection (including miliary tuberculosis), lymphoproliferative diseases and demyelination can occur. These drugs are very expensive, but TNF antibody therapy is becoming the standard of care for fistulas and refractory disease.

9.

Surgery is reserved for the complications of Crohn’s disease (e.g. internal fistula with abscess, intestinal obstruction not responding to medical management). The best operation is resection. Strictureplasty may allow relief of localised obstruction without the deleterious effects of multiple resections.

10.

When a total colectomy is needed, a standard ileostomy is the procedure of choice. The recurrence rate of the disease is unchanged by surgery.

Colon cancer

This is a particularly common tumour that usually develops in those 50 years of age or older, although patients at risk with hereditary syndromes will present at a younger age. Because early disease is curable, there has been increased interest recently in colon cancer screening. Hence, a history of polyps or colon cancer is increasingly likely to be encountered in the examination.

Table 7.6

Immunosuppression in inflammatory bowel disease

FBC = full blood count; LFTs = liver function tests; 6MP = 6 mercaptopurine; TPMT = thiopurine methyltransferase

The history

1.

The patient may have been diagnosed recently as having a colon cancer. In this case, ascertain the reasons for diagnostic testing. A recent change in bowel habit or bright red blood per rectum (from a rectal or left-sided colon cancer), symptoms of anaemia, new-onset abdominal pain or symptoms suggestive of small bowel obstruction (with a slow-growing caecal cancer) may have been the presenting complaint. There may have been symptoms from involvement of the bladder or female genital tract owing to local invasion. Sacral plexus pain is a very late manifestation.

2.

If colon cancer was identified, determine the staging tests and treatment undertaken. If radiotherapy was given to the pelvis, enquire about any ongoing proctitis or cystitis.

3.

Determine whether the patient understands the prognosis and ascertain the social support network. Ask whether stoma therapy has been discussed.

4.

If the patient has a history of polyps, try to determine from the patient whether these were adenomatous polyps, their approximate size and number. Patients are often rather unclear about these matters and when discussing with the examiners you may need to request information from the medical record. Adenomatous polyps may be tubular or villous (or tubulovillous); invasive cancer is more likely in larger polyps (10% of those >2.5 cm are malignant). If polyps were detected, ask the patient whether surveillance colonoscopy has been conducted in the past, when this began and how often. A repeat colonoscopy after 3 years in those patients without previously documented colonic cancer who have a documented large (>1 cm) adenomatous polyp or multiple (3–10) polyps is generally recommended (

Table 7.7

), although surveillance needs to be tailored to other risk factors, including the family history. A serrated polyp is usually flat and can lead to colon cancer through a different pathway (hypermethylation of genes).

Table 7.7

Current recommended follow-up colonoscopy intervals in patients otherwise at average risk based on findings at initial colonoscopy (American Gastroenterology Association, 2012)

| BASELINE COLONOSCOPY RESULT | RECOMMENDED SURVEILLANCE INTERVAL (YEARS) |

| No polyps or small (<10 mm) hyperplastic polyps in rectum or sigmoid | 10 |

| 1–2 small (<10 mm) tubular adenomas | 5-10 |

| 3–10 tubular adenomas or one or more tubular adenomas ≥10 mm | 3 |

| 10 adenomas | <3 |

| One or more villous adenomas or sessile serrated polyp ≥ 10mm | 3 |

5.

The family history needs to be carefully obtained for any patient with a history of polyps or colon cancer in the past. If the patient describes having had thousands of adenomatous polyps throughout the large bowel, then familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is the diagnosis (until proven otherwise). These polyps usually occur after puberty and most individuals are affected by the age of 25 years. If the colon is not removed, almost all will have colon cancer before the age of 40. In this type of clinical case, ask about the presence of any soft-tissue or bony tumours (Gardiner’s syndrome) or tumours in the central nervous system (Turkot’s syndrome), which are variants of FAP.

Most patients with FAP will have undergone a total colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis. Ask about continence and stool frequency if this operation has been performed. Screening for duodenal and periampullary cancers every 1 to 3 years by endoscopy is generally recommended.

Ask whether any offspring of a patient with this condition have been screened. Flexible sigmoidoscopy on an annual basis is recommended. DNA testing of peripheral blood mononuclear cells for the presence of the mutated

APC

gene at puberty is also useful (after first testing affected relatives to validate the

APC

mutation presence) in screening offspring.

The MuTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) syndrome (autosomal recessive) can present just like FAP.

If there is a strong family history of colon cancer, consider the possibility of Lynch syndrome (see below). There is a 70% lifetime risk of colon cancer in this autosomal dominant disease. There is often also a family history of either ovarian or endometrial carcinoma. Members of such families are typically screened by colonoscopy biennially beginning at the age of 25 years, as well as undergoing pelvic ultrasonography and endometrial biopsies.

6.

Enquire about any history of documented inflammatory bowel disease. The risk of colorectal cancer in a patient with ulcerative colitis is small during the initial 7–10 years after pancolonic disease development, but then increases approximately 1% per year. Ask whether colonoscopic surveillance has been undertaken or not. Patients with Crohn’s colitis should now also be offered similar surveillance.

7.

Ask whether there has been any history of possible septicaemia.

Streptococcus bovis

or

Clostridium septicus

bacteraemia indicates an underlying high risk of occult colon cancer and requires aggressive investigation.

8.

Haematomas of the gastrointestinal tract with mucocutaneous pigmentation (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome) increase the risk of both large and small bowel cancer, as well as breast, uterine and ovarian cancers. Affected patients should undergo surveillance by colonoscopy and gastroscopy every 3 years from 18 years of age.

9.

Determine whether there is any history of a ureterosigmoidostomy for correction of congenital exstrophy of the bladder, which increases the risk of colon cancer 15–30 years later.

10.

Diabetes mellitus, renal transplant and acromegaly may be associated with an increased risk; regular full-dose aspirin use may reduce the risk of colon cancer.

The examination

1.

Look for evidence of jaundice or anaemia.

2.

If the patient is currently undergoing 5-fluorouracil-derived chemotherapy, look at the palms and soles for evidence of hand–foot syndrome (very tender, symmetrical erythema) (

Fig 7.6

).

FIGURE 7.6

Hand, foot and mouth syndrome. Skin

reaction to docetaxel. Note erythema and edema of the palms in this patient.

A T Skarin.

Atlas of diagnostic oncology

. 4th edn, Fig 21.4F. Mosby, Elsevier, 2010, with permission.

3.

Carefully examine the abdomen, in particular looking for any evidence of malignant deposits in the liver or other intraperitoneal masses or skin changes that are consistent with radiotherapy. Record any scars on the abdomen.

4.

Results of a rectal examination need to be obtained.

5.

Other lymph node groups should be examined and evidence of metastatic malignancy elsewhere (e.g. the lungs, bones or brain) should be sought.

6.

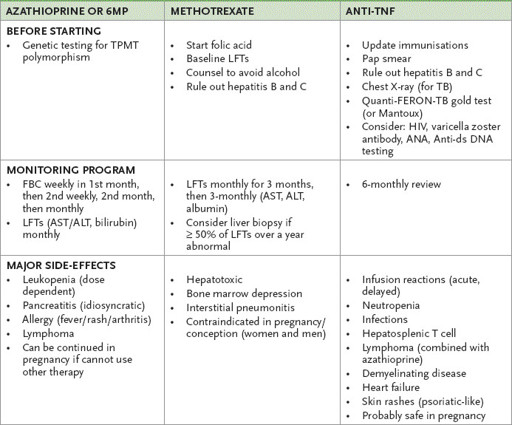

Look for the pigmentation of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (see

Fig 7.7

).

FIGURE 7.7

Pigmentation of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. (a) Buccal mucus in the mouth (b) Discreet brown-black

lesion of lips.

(a) F S McDonald (ed.).

Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine

. With permission.©Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press. (b) D V Jones et al., in M Feldman et al.,

Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal disease

, 6th edn, Ch 112. Saunders, Elsevier, 1998, with permission.