Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (39 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

3.

Ask about symptoms of connective tissue disease. Joint pain or swelling may also occur in acute sickle cell crisis and especially affect the knees and elbows. Refractory leg ulcers occur in hereditary spherocytosis and sickle cell syndromes. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other connective tissue disorders may be associated with warm antibody immunohaemolytic anaemia. Lymphoma is associated with both warm and cold antibodies and anaemia.

4.

A history of pain in the abdomen, back and elsewhere suggests sickle cell anaemia or paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Congenital haemolytic anaemias can result in pigment gallstones that can cause symptomatic cholelithiasis and even acute cholecystitis; these episodes can be confused with acute crises.

5.

Ask about neurological problems. Spinal cord lesions can occur with hereditary spherocytosis. Paraspinal masses (extramedullary haemopoiesis) are a rare complication of any hereditary haemolytic anaemia or lymphoma. Acute sickle cell crisis can also result in neurological impairment, particularly stroke. Tertiary syphilis may cause paroxysmal cold haemoglobinuria. In thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

there are often fluctuating neurological abnormalities. For other features of TTP, remember the mnemonic FAT RN:

F

ever

A

naemia (microangiopathic haemolytic)

T

hrombocytopenia

R

enal failure

N

eurological abnormalities

6.

List all drugs that have been taken. For example, methyldopa, penicillin and quinidine can cause warm antibody immunohaemolytic anaemia, and antimalarials, sulfonamides and nitrofurantoin cause haemolysis in subjects deficient in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD).

Note:

Between 10% and 20% of people taking methyldopa have a positive direct Coombs’ test, but only a small minority of these develop haemolysis. The drug alters Rh antigens so that antibodies are produced against them, which then cross-react with normal Rh antigens. The indirect Coombs’ test is therefore positive, even when the drug is not added to the test. The other drugs produce an indirect Coombs’ test result only when the drug is added to the mixture, because in that case the antibodies are directed against a combination of drug and cell membrane. Fludarabine, which is increasingly used as first-line treatment of chronic lymphatic leukaemia in patients under the age of 65 and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, may cause exacerbation of warm autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. When fludarabine is combined with the anti-CD20 monoclonal rituximab, AIHA is mitigated.

7.

Enquire about any operations, particularly mechanical heart valve replacement (10% of those with aortic valve prostheses have significant haemolysis; this percentage is lower with mitral valve prostheses unless a paravalvular leak is present, as the pressure gradient is lower). Severe haemolysis in these patients suggests a paravalvular leak. Consider the other occasional cause of haemolysis within the circulation – external trauma, such as occurs in joggers who wear thin-soled shoes, and the traditional group, bongo drummers. In these cases, haemolysis is intravascular and haemosiderinuria is characteristic.

8.

Determine the patient’s ethnic background (e.g. Greeks or Italians may inherit the beta-thalassaemia trait; both thalassemias are common on the subcontinent and alpha thalassaemia is common in China and Southeast Asia; black men may have G6PD deficiency).

9.

The patient may have an underlying medical problem associated with the risk of developing microvascular fragmentation of red cells. These conditions include: disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which is usually caused by vessel wall changes related to an underlying disease, such as disseminated malignancy, renal graft rejection or malignant hypertension; TTP, which is of unknown aetiology; and haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS, with similar features to TTP), which can follow gastroenteritis caused by

E. coli 0157:H7

infection (do not treat these cases with an antibiotic, since this increases the risk of HUS!).

The examination

1.

A careful haematopoietic system examination is required. The characteristic ‘chipmunk’ facies in a young person with thalassaemia is caused by maxillary marrow hyperplasia and frontal bossing.

2.

Look for pallor and icterus.

3.

Examine the heart for a valve prosthesis or severe aortic stenosis (traumatic haemolysis). Profound anaemia may be associated with high-output cardiac failure. An iron overload state in thalassaemia major from repeated transfusions may cause skin pigmentation, cardiac failure and hepatomegaly.

4.

Carefully palpate for the spleen; splenomegaly from any cause (see

Table 16.21

) may result in haemolysis. Lymphadenopathy may indicate lymphoma (associated with warm or cold antibody haemolysis), chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or in practice glandular fever (cold agglutinin haemolysis).

5.

Signs of chronic liver disease should be noted – in severe cirrhosis spur-cell (acanthocyte) anaemia is occasionally observed.

6.

Examine for focal neurological signs. Look in the fundi – retinal detachment, retinal infarcts and vitreous haemorrhages can be manifestations of sickle cell anaemia; Kayser-Fleischer rings may be present in the cornea when haemolysis is caused by Wilson’s disease.

7.

Joint swelling and tenderness, and occasionally aseptic necrosis of bone (e.g. neck of femur), also occur in sickle cell anaemia; bony infarcts may become infected (e.g.

Salmonella

osteomyelitis).

8.

Look for leg ulceration. Note any signs of connective tissue disease.

9.

Test the urine – urobilinogen may be present with haemolysis; it may be dark from haemoglobin in intravascular haemolysis and the sediment may be abnormal (e.g. TTP).

10.

Fever may occur with septicaemia or malaria-associated haemolysis, with acute crises in sickle cell anaemia and in TTP.

Investigations

It is important to confirm that haemolysis is present, exclude intravascular haemolysis and perform tests to determine the aetiology. The history and physical examination may have provided hints about the likely aetiology.

1.

Ask for the results of a blood count, reticulocyte count, serum bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase. Haemolysis is likely to be present if there is a normochromic normocytic anaemia with an increased reticulocyte count (but reticulocytosis also occurs with blood loss or partially treated anaemia) and release of red blood cell components (increased unconjugated bilirubin and, more variably, lactate dehydrogenase).

2.

Usually serum haptoglobin is absent and haemosiderin is present in the urine. Intravascular haemolysis is documented by the presence of methaemalbumin in the plasma (Schumm’s test) and, less often, of haemoglobin in the urine.

3.

The presence of fragmented red cells (schistocytes) suggests valve haemolysis, DIC and TTP (or HUS). TTP (or HUS) is very likely when fragmented red cells occur in association with thrombocytopenia and normal coagulation studies; look for renal and neurological impairment.

4.

The blood film usually shows polychromasia; it may show other red cell changes (

Tables 8.1

and

8.2

). In thalassaemia, the anaemia is often hypochromic and always significantly microcytic.

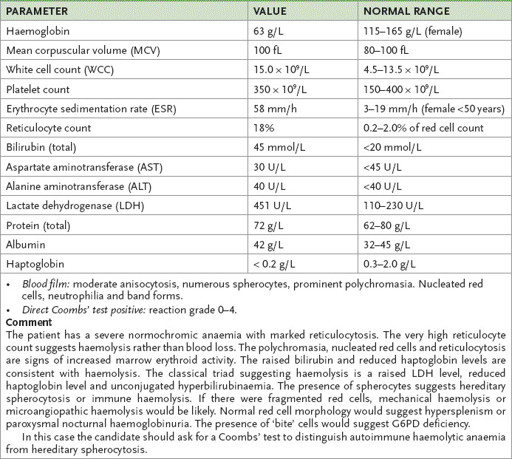

Table 8.1

Full blood count and liver function tests from a female patient with autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA)

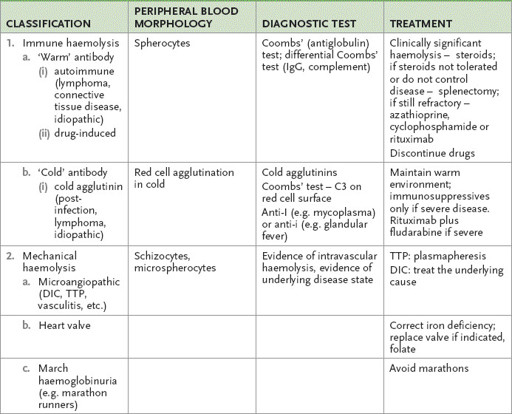

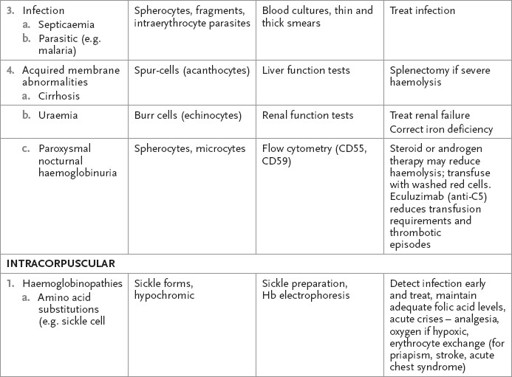

Table 8.2

Haemolytic anaemia

DAF = decay accelerating factors; DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation; G6PD = glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; Hb = haemoglobin; HbH = haemoglobin H; TTP = thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

5.

If a congenital intracorpuscular defect seems unlikely, ask for a Coombs’ test to determine whether the anaemia is immunohaemolytic. The polyspecific direct Coombs’ test measures the ability of anti-IgG and anti-C3 to agglutinate the patient’s red blood cells. Warm antibodies (80% of cases) react at body temperature and may occur with lymphoma (usually non-Hodgkin’s), chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, solid tumours (lung, colon, kidney and ovary), SLE and drugs, or may be idiopathic. They are usually IgG antibodies directed at the Rh antigens. Cold reactive antibodies are precipitated by exposure to room temperature (‘cold’) – cold agglutinin disease (IgM antibodies) may occur acutely with glandular fever, mycoplasma infection or hepatitis C, and chronically may be caused by lymphoma or may be idiopathic; paroxysmal cold haemoglobinuria (IgG antibodies) is rare.

6.

If the haemoglobinuria occurs usually at night and there is pancytopenia and venous thrombosis, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) should be strongly suspected (an acquired stem cell disease secondary to a defective

PIG-A

gene). The disease may also be associated with aplastic anaemia, in which the neutrophil alkaline phosphatase score is low (but this test is now rarely performed). The sucrose lysis and acid haemolysis (Ham’s) test used to be performed. The most reliable test now is analysis by flow cytometry for glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked proteins (e.g.

CD55

or decay-accelerating factors (DAF) on the red cell surface, and

CD59

or homologous restriction factor). PNH, which is an acquired clonal disease, is a result of a mutation that causes faulty or absent production of the GPI anchor molecule. Various linked proteins are missing from the red cell surface and, as a result, the cells are not protected from lysis by complement.

Tests for other causes of haemolysis are presented in

Table 8.2

.

Treatment

This depends on the underlying disease process, which should be reversed if possible (e.g. drug withdrawal, treatment of transplant rejection, adoption of another musical instrument) (see

Table 8.2

).

1.

Steroids are useful in immunohaemolytic anaemia caused by warm-reactive antibodies. The usual approach is to commence at a starting dose of 1 mg/kg/day of prednisolone. The haemoglobin level will usually rise within the first week. Concurrent use of folate is often recommended. Once a normal haemoglobin level has been achieved, the steroid dose must be tapered slowly. Splenectomy works as well as steroids, and is indicated in poorly responsive or resistant disease. Immunosuppressive treatment is reserved for those who do not respond to steroids and splenectomy. Azathioprine and cyclophosphamide have each been used with some benefit. Response takes 2 to 3 months. Normal human immunoglobulin is often effective. There is increasing evidence of the efficacy of rituximab in very refractory cases, but AIHA remains an ‘off label’ indication.