Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (40 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

2.

Transfusion is not usually indicated unless there is symptomatic anaemia with a haemoglobin level <90 g/L; it may exacerbate haemolysis. The antibody in immunohaemolytic anaemia is likely to react with all normal donor cells so that standard cross-matching is not possible.

Laboratory testing in such cases most often reveals a ‘pan agglutining’ autoantibody. Occasionally the autoantibody has Rh antigen specificity and donor red cells lacking the antigen can be safely transfused under close observation.

3.

When cold-reactive antibodies are responsible, steroid treatment is less effective. Avoidance of cold can be helpful. The disease tends to progress unless the underlying malignancy can be treated.

4.

The chimeric antibody, rituximab, which attaches to the CD20 binding site on B lymphocytes and induces their destruction, may be useful in severe cases of resistant autoimmune haemolytic anaemia.

5.

The acute haemolytic episodes of patients with G6PD deficiency are self-limiting (only older red blood cells are affected) and require no specific treatment. Hydration should be maintained to protect renal function. Patients should be warned to avoid precipitating factors (e.g. broad beans, antimalarials and sulfonamides).

6.

Valve haemolysis may be improved by iron supplements and an increase in haemoglobin (reduced cardiac output). Paravalvular leaks often need to be repaired and occasionally the prosthetic valve may have to be replaced with a larger one.

7.

TTP is now treated with plasmapheresis, which improves the mortality rate from almost 100% to 10%. Twice-daily treatment is combined at first with high-dose steroids. Even severe neurological deficit, including coma, may be reversible.

Anti-platelet drugs are of uncertain benefit. Cyclophosphamide and vincristine are used when plasmapheresis has been unsuccessful. Relapse (10%) can usually be treated successfully. Platelet transfusions must be avoided as they exacerbate thrombosis. The preferred replacement solution is cryosupernatent or fresh frozen plasma (FFP).

8.

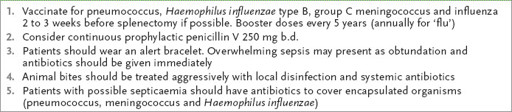

Splenectomy is virtually curative for patients with hereditary spherocytosis and elliptocytosis (only 10% have severe haemolysis), and may be useful in selected patients with massive splenomegaly, immunohaemolytic anaemia, certain haemoglobinopathies and enzymopathies. All patients undergoing splenectomy should receive pneumococcal vaccine preoperatively if possible. Sometimes, prophylactic treatment with penicillin is recommended for 2 years following splenectomy (

Table 8.3

). Failure of splenectomy to control haemolysis may be caused by an accessory spleen (which can be detected by a liver–spleen scan).

Table 8.3

Treatment advice for patients having a splenectomy

9.

PNH can be treated with washed red cell transfusions and steroids. Heparin and warfarin should be used for thrombotic episodes. Bone marrow transplant may be curative. Trials of the monoclonal antibody eculizimab, which blocks the complement cascade below C5, have shown major benefits with a reduction in transfusion requirements and reduced incidence of thrombosis; the drug prevents the complement-driven haemolysis in PNH. The Commonwealth Department of Health has a specific program to fund the administration of eculizimab for Australian patients on a PNH registry.

Thrombophilia

The discovery of new thrombophilic factors has made the patient with recurrent or even a single thrombotic episode a very suitable long case. Suspect this possibility if the patient is under 50 or has a family history of recurrent thromboses (

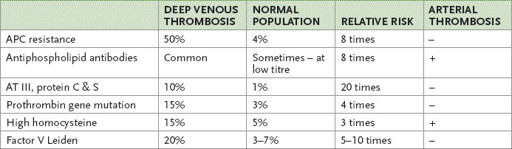

Table 8.4

).

Table 8.4

Occurrence of and risk associated with the thrombophilic factors

APC = activated protein C; AT = antithrombin.

The history

1.

Ask about the reasons for any recent admissions to hospital. There may have been a recent episode of venous or arterial thrombosis or the patient may have been admitted for a procedure that has a high risk of thrombosis.

2.

Ask about the nature of thrombotic episodes. These may have been arterial or venous, or both. Find out how often the problem has occurred and what part of the body was involved.

3.

Ask whether a thrombotic tendency has been identified and how this was done (the patient may know).

4.

Ask what anticoagulation therapy is currently being used. The possibilities include intravenous unfractionated heparin, fractionated heparin given subcutaneously, low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, aspirin or (less likely) clopidogrel or dipyridamole. Since 2010, a number of novel oral anti-coagulants (NOACs) have become available, including the anti Xa agents apixaban, rivaroxaban and the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigitran. None of these appears superior to warfarin in terms of recurrent thrombosis, but there is the major benefit of the lack of need for monitoring. None is reversible in the setting of severe trauma or haemorrhage.

5.

If the patient is or has been on treatment with warfarin, find out how much he or she understands about the drug, including the importance and necessary frequency of international normalised ratio (INR) testing and the target INR. The patient should probably know the most recent INR result and have some understanding of food and drug interactions with warfarin. For a patient on warfarin, ask about the usual frequency of blood tests and whether practical difficulties have been encountered in getting to the pathology laboratory. Ask who usually relays INR results and dose changes to the patient, and whether the patient has ever used a home INR tester.

6.

Enquire about a family history of thrombosis and whether the patient’s own problem has led to the testing of other family members. In general, 50% of first-degree relatives will inherit the mutation if there is an identified autosomal dominant hereditary factor (e.g. protein C, protein S and antithrombin deficiency). Remember, a family history of thrombosis greatly increases a patient’s risk. Patients with a thrombophilic defect, but without a family history of thrombosis, have only a slightly increased risk. The absence of a family history may make thrombophilia testing irrelevant, as positive tests will not likely change management.

7.

Ask about other factors that may increase thrombotic risk, including smoking, oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives, pregnancy, malignancy, recent surgery and immobility. Long aeroplane flights are controversial as a risk factor, but have received extensive discussion in the popular press.

8.

If the event has followed a surgical operation, ask what prophylaxis was used to try to prevent thrombosis.

9.

In women, ask about previous unexplained miscarriages. This can be associated with the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, which are autoantibodies against various platelet surface molecules, including phospholipids. These include lupus anticoagulant (which prolongs the aPTT), anticardiolipin and anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies. Consider this possibility too if there is a history of unusual thromboses or eclampsia and pre-eclampsia.

10.

Specifically ask about previous myocardial infarction. The occurrence of myocardial infarction in young women with normal coronary arteries has been associated with factor V Leiden mutation.

11.

Ask whether there have been chronic venous problems in the legs. Damage to the venous system can cause chronic oedema and ulceration that can be quite disabling (post-thrombotic syndrome). If there have been chronic problems, asking detailed questions about their effect on the patient’s life is essential.

12.

Ask about the congenital abnormality, homocysteinuria, which is associated with a Marfanoid habitus and premature strokes and coronary artery disease. Homocysteine is a thrombophilic agent.

13.

Ask about features of PNH – recurrent episodes of dark urine, anaemia and pancytopenia.

The examination

1.

Note the presence or absence of an intravenous heparin infusion. If present, look at the infusion rate.

2.

Note the presence of obesity and look for signs of venous insufficiency from previous venous thromboses.

3.

Examine the legs for oedema, venous ulceration and venous valvular insufficiency.

4.

Check the peripheral pulses for evidence of arterial obstruction.

5.

Note the presence of abdominal wall bruising from subcutaneous low-molecular weight heparin injections.

6.

There may be evidence of a myeloproliferative disorder, SLE, nephrotic syndrome (oedema) or a malignancy.

Investigations

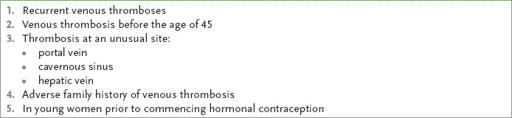

There is a case now for testing anyone with a significant arterial or venous thrombosis for thrombophilic factors (

Tables 8.4

and

8.5

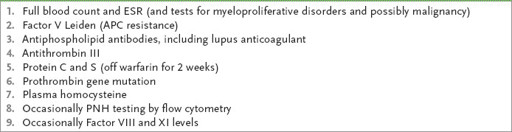

), especially those with a family history of thromboembolic disease. Certainly, unusual or repeated thromboses should be investigated, as set out below. The currently available routine screening tests are listed in

Table 8.6

.

Table 8.5

Indications for thrombophilia investigations

Table 8.6

Tests for thrombophilia

1.

Factor V Leiden

is an abnormal factor V molecule. The abnormality is caused by a point mutation that affects the cleavage site on the activated molecule. The abnormal factor V is resistant to neutralisation by activated protein C (APC), which forms part of the natural anticoagulation pathway. The condition is also called APC resistance. The mutation occurs in 4% of the general population in Australia and in up to 50% of people with a family history of recurrent venous thrombosis. The condition is autosomal dominant. The heterozygous state is associated with an eightfold increase in venous thrombotic risk; the homozygous state also occurs and these people have 100 times the average risk.

The thrombotic risk is higher for women with this condition because of the additional risk associated with pregnancy and the use of oral contraceptives containing oestrogen. Use of these drugs causes a 35 times increased risk of a thrombotic event (approximately a 3% risk over 10 years). The mechanism is probably that of lowering antithrombin III levels.