Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (67 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

4.76Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Outside the parameters of normality

In situations where the midwife is faced with factors not deemed to be normal, she must use

her knowledge and clinical judgment about the most appropriate way forward. If she can justify what she is doing – keeping the woman and her baby the focus of providing safe effective care, then her clinical judgement should not be called to question. For example, in a situation where transfer to hospital from a birth centre or home birth is being considered, then the whole picture must be evaluated. This will include taking into consideration not only the facts presenting at the time, but also the background, the woman’s obstetric history and whether there is time to safely transfer. As identified by the NMC (2012) midwives must seek help and support from appropriate professionals when there are deviations from the norm.

Artificial rupture of membranes

Artificially rupturing the membranes along with the use of intravenous oxytocin became common practice in 1969 after O’Driscoll pioneered the managed labour to speed up the process of birth to accommodate the move from birth at home to birth in hospital. His impres- sion was that this intervention did not result in untoward outcomes with some suggestion that women were satisfied with such care (O’Driscoll et al. 1969). It is now seen as an intervention to be considered when other possibilities have been exhausted in a normal physiological labour (Walsh 2011). In midwifery-led care, the midwife would not rupture the membranes unless there was a clinical reason to do so. The cushion of amniotic fluid in front of the baby’s head is protec- tive and intact membranes allow the amniotic fluid to act as a shock absorber throughout contractions. If labour progress has stalled and the midwife and mother have done everything they can to help labour move forward, it may be appropriate to transfer care to the obstetricians. However, before this happens, since this will probably be the first intervention employed by the obstetricians, artificial rupture of membranes by the midwife at this point may be all that is required and the care can continue midwife-led, removing the need to transfer care.

Equally there may be occasions when the midwife detects an abnormality of the fetal heart. This may raise alarm to the potential for distress of the fetus. Detecting the presence of meco- nium by either artificially rupturing the membranes, or if it becomes evident on spontaneous rupture, gives the midwife more information on which to base her care and advice.

Pain management in labour

Women have a choice of different types of analgesia and other forms of pain management in

labour. It is the midwife’s responsibility to ensure the woman understands how each form of pain relief will affect them, their baby and the course of their labour.

Figure 7.7

Woman using water for relaxation in labour. Source: Reproduced with permission from

Green.

155A summary of the evidence from Cochrane Systematic Reviews suggests that non- pharmacological methods such as: immersion in water (see Figure 7.7), relaxation, acupuncture and massage may improve management of labour pain, with few adverse effects, although their efficacy is unclear (Jones et al. 2012). Hypnotherapy and acupuncture have been acknowledged as having benefits to assisting women cope with labour (Smith et al. 2009). The popularity is increasing for considering water immersion for coping with labour and giving birth. Evidence suggests that its use in the first stage of labour reduces the need for epidural analgesia and the length of labour (Cluett and Burns 2009).Pharmacological methods including local anaesthetic nerve blocks or non-opioid drugs also improve management with few adverse effects (Jones et al. 2012). There is evidence to suggest that epidurals relieve pain, but can increase the numbers of instrumental births and run the risk of causing hypotension, motor blocks (hindering leg movement), fever and urine retention (Jones et al. 2012). It could be argued there are pros and cons; at times an epidural can be a valuable part of modern medicine when complications occur or if requested by the woman as an option for managing pain in labour. If a woman is so anxious and tense in response to the pain of contractions the optimal hormonal balance may be hindered. By having an epidural the woman relaxes and the oxytocin release improves; it can often be seen at the next vaginal examination that the cervix is fully dilated with good descent of the presenting part.

155A summary of the evidence from Cochrane Systematic Reviews suggests that non- pharmacological methods such as: immersion in water (see Figure 7.7), relaxation, acupuncture and massage may improve management of labour pain, with few adverse effects, although their efficacy is unclear (Jones et al. 2012). Hypnotherapy and acupuncture have been acknowledged as having benefits to assisting women cope with labour (Smith et al. 2009). The popularity is increasing for considering water immersion for coping with labour and giving birth. Evidence suggests that its use in the first stage of labour reduces the need for epidural analgesia and the length of labour (Cluett and Burns 2009).Pharmacological methods including local anaesthetic nerve blocks or non-opioid drugs also improve management with few adverse effects (Jones et al. 2012). There is evidence to suggest that epidurals relieve pain, but can increase the numbers of instrumental births and run the risk of causing hypotension, motor blocks (hindering leg movement), fever and urine retention (Jones et al. 2012). It could be argued there are pros and cons; at times an epidural can be a valuable part of modern medicine when complications occur or if requested by the woman as an option for managing pain in labour. If a woman is so anxious and tense in response to the pain of contractions the optimal hormonal balance may be hindered. By having an epidural the woman relaxes and the oxytocin release improves; it can often be seen at the next vaginal examination that the cervix is fully dilated with good descent of the presenting part.

Midwifery craftsmanship

A midwife learns her craft through experience; repeatedly noticing subtle patterns and com-monalities in women’s behaviour. This experiential knowledge forms the bedrock of an indi- vidual midwife’s skill. Although we focus on normality, most midwives work in environments where the use of interventions can be common and routine. Having confidence in midwifery156rather than just concentrating on normality is essential for a midwife; since it is not possible to make an abnormal situation normal, but the midwife can care for the woman with the same midwifery skill. Applying midwifery knowledge and skills complements the obstetric care a woman may require. The desired outcome is that women can still feel in control even if the birth experience is not what they had hoped (Fahy and Hastie 2008). The role of the woman within the team is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2: ‘Team working’.

Judicious use of midwifery skills and knowledge is vital, ensuring that clinical skills have been appropriately employed throughout to support the midwife in her accountability; utilising what is known about physiology and the individual women and having confidence in the woman’s ability to birth. Being a watchful guardian with honed clinical skills and the knowledge to be able to use all that information is what makes the midwife who she is. There is no place for routine and ritual, without justification. Doing things just because we have always done them is not good enough, but doing the right things with the woman’s understanding and consent, even if that means something the woman may prefer to avoid, is good practice of an educated midwife.

Judicious use of midwifery skills and knowledge is vital, ensuring that clinical skills have been appropriately employed throughout to support the midwife in her accountability; utilising what is known about physiology and the individual women and having confidence in the woman’s ability to birth. Being a watchful guardian with honed clinical skills and the knowledge to be able to use all that information is what makes the midwife who she is. There is no place for routine and ritual, without justification. Doing things just because we have always done them is not good enough, but doing the right things with the woman’s understanding and consent, even if that means something the woman may prefer to avoid, is good practice of an educated midwife.

Medical intervention

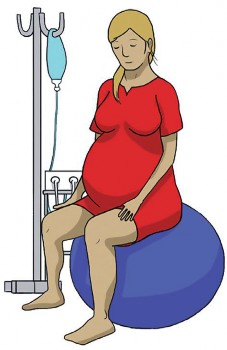

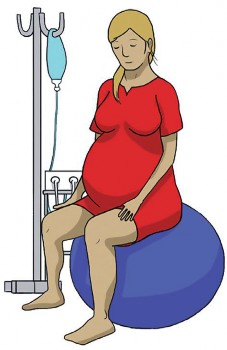

It is acknowledged that modern Western technology and evidence-based medicine has indis-putably contributed to safer childbirth, reducing maternal and fetal mortality. However it is questionable whether the benevolent aspect of paternalism has gone too far and being at the detriment of women’s autonomy in childbirth (Walsh et al. 2004). It is part of the midwives’ role to keep elements of normality as part of the holistic care for women, for those also needing a doctor and medical intervention. Figure 7.8 illustrates a woman receiving some medical inter- vention, using different positions to help labour progress.

Figure 7.8

Figure 7.8

Woman on a birthing ball receiving medical intervention. Source: Reproduced with permission from J. Green.

Meeting the baby

The moment a mother meets her baby has been awaited with anticipation. Women’s expecta-tions will differ greatly, for some there may be fear and sense of responsibility; some may not be intending to be the social parent of the child and maybe facing some very difficult times. (See Chapter 5: ‘Parenthood’, where defining parents is discussed in greater depth). Whatever the situation, this is a moment in the lives of the parents and the newborn that will stay with them both forever. The midwife has an opportunity to assist in making this moment memorable and the most optimal physiologically.Midwives must be alerted to the sudden change of environment for the newborn; a stimulat- ing environment may potentially trigger stress responses in the baby. Very little evidence exists about the emotional status of a newborn, although it is known there is an increase in fetal catecholamines in labour in response to birth (Coad and Dunstall 2011). Providing a gentle transition for the newborn simply seems a logical approach. The benefits of skin-to-skin contact for mother and baby are well recognised (Anderson et al. 2006). Skin-to-skin and gentle han- dling may help to instil a calmness that will stay with the baby in the early weeks. The joy of birth and bonding potential is needed even more if labour has resulted in intervention and an assisted or traumatic birth, for example caesarean section or an instrumental birth.

Third stage management

When discussing the third stage of labour with a woman, it is really important to ensure thatshe understands this can be achieved without intervention as the natural conclusion of a normal uncomplicated labour (Soltani 2008), only separating the baby and the placenta and mem- branes once the baby has been born. Alternatively the third stage can be actively managed by the midwife with uterotonic drugs, clamping and cutting the cord and controlled cord traction. Giving information about the third stage of labour would form part of birth planning and should include discussion about both methods of delivery and the benefits and risks for mother and baby. However, the woman should be aware that this decision does not need to be made until the end of the second stage of labour, with full information of the clinical picture.Where there is a risk of the uterus not contracting to expel the placenta and membranes and achieve haemostasis of the blood vessels at the placental site, or other risk factors for haemor- rhage. The woman should be advised regarding active management of the third stage with uterotonic drugs and controlled cord traction (NICE 2007). By giving a simple explanation of the physiology of the third stage, the woman can make the most appropriate decision for her. Some women have no strong feeling regarding this part of labour, wishing to get it over with as soon as possible allowing them to concentrate on their baby, whilst for others it is extremely important.Midwives should ensure they have the skills for both physiological and managed delivery of the placenta, avoiding mixing elements of the two methods since this may have implications on outcome (Begley et al. 2011). Skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding at this point is a moth- er’s well-deserved reward for her hard work. This helps the mother to be more relaxed and produce the hormonal response to encourage separation of the placenta. Soltani (2008) has shown that gravity too can play its part in helping the placenta to separate and expel from the body. It is suggested the woman should be in an upright position for this part of labour.Birth in water may alter the timing of use of drugs if active management of the placenta is to be employed, with midwives waiting until the woman has exited the pool before starting the process for active management. The reality in practice is that midwives and doctors whilst

157158broadly following the principles of active management do vary in their techniques, and as evidence has emerged to support delaying the clamping and cutting of the cord, to allow full transfusion of blood to the baby, this too has further complicated management (Farrar et al. 2009). Partners or women themselves may want to be involved in the cutting of the umbilical cord, seeing this as a symbolic moment where baby becomes truly independent.

157158broadly following the principles of active management do vary in their techniques, and as evidence has emerged to support delaying the clamping and cutting of the cord, to allow full transfusion of blood to the baby, this too has further complicated management (Farrar et al. 2009). Partners or women themselves may want to be involved in the cutting of the umbilical cord, seeing this as a symbolic moment where baby becomes truly independent.

Lotus birth involves physiological delivery of the placenta, but the cord and placenta remain intact until the cord separates naturally from the baby. The placenta may be treated with salt and herbs and is wrapped with the baby following birth. This practice whilst not common is increasingly requested.

Lotus birth involves physiological delivery of the placenta, but the cord and placenta remain intact until the cord separates naturally from the baby. The placenta may be treated with salt and herbs and is wrapped with the baby following birth. This practice whilst not common is increasingly requested.

155A summary of the evidence from Cochrane Systematic Reviews suggests that non- pharmacological methods such as: immersion in water (see Figure 7.7), relaxation, acupuncture and massage may improve management of labour pain, with few adverse effects, although their efficacy is unclear (Jones et al. 2012). Hypnotherapy and acupuncture have been acknowledged as having benefits to assisting women cope with labour (Smith et al. 2009). The popularity is increasing for considering water immersion for coping with labour and giving birth. Evidence suggests that its use in the first stage of labour reduces the need for epidural analgesia and the length of labour (Cluett and Burns 2009).Pharmacological methods including local anaesthetic nerve blocks or non-opioid drugs also improve management with few adverse effects (Jones et al. 2012). There is evidence to suggest that epidurals relieve pain, but can increase the numbers of instrumental births and run the risk of causing hypotension, motor blocks (hindering leg movement), fever and urine retention (Jones et al. 2012). It could be argued there are pros and cons; at times an epidural can be a valuable part of modern medicine when complications occur or if requested by the woman as an option for managing pain in labour. If a woman is so anxious and tense in response to the pain of contractions the optimal hormonal balance may be hindered. By having an epidural the woman relaxes and the oxytocin release improves; it can often be seen at the next vaginal examination that the cervix is fully dilated with good descent of the presenting part.

155A summary of the evidence from Cochrane Systematic Reviews suggests that non- pharmacological methods such as: immersion in water (see Figure 7.7), relaxation, acupuncture and massage may improve management of labour pain, with few adverse effects, although their efficacy is unclear (Jones et al. 2012). Hypnotherapy and acupuncture have been acknowledged as having benefits to assisting women cope with labour (Smith et al. 2009). The popularity is increasing for considering water immersion for coping with labour and giving birth. Evidence suggests that its use in the first stage of labour reduces the need for epidural analgesia and the length of labour (Cluett and Burns 2009).Pharmacological methods including local anaesthetic nerve blocks or non-opioid drugs also improve management with few adverse effects (Jones et al. 2012). There is evidence to suggest that epidurals relieve pain, but can increase the numbers of instrumental births and run the risk of causing hypotension, motor blocks (hindering leg movement), fever and urine retention (Jones et al. 2012). It could be argued there are pros and cons; at times an epidural can be a valuable part of modern medicine when complications occur or if requested by the woman as an option for managing pain in labour. If a woman is so anxious and tense in response to the pain of contractions the optimal hormonal balance may be hindered. By having an epidural the woman relaxes and the oxytocin release improves; it can often be seen at the next vaginal examination that the cervix is fully dilated with good descent of the presenting part.Midwifery craftsmanship

A midwife learns her craft through experience; repeatedly noticing subtle patterns and com-monalities in women’s behaviour. This experiential knowledge forms the bedrock of an indi- vidual midwife’s skill. Although we focus on normality, most midwives work in environments where the use of interventions can be common and routine. Having confidence in midwifery156rather than just concentrating on normality is essential for a midwife; since it is not possible to make an abnormal situation normal, but the midwife can care for the woman with the same midwifery skill. Applying midwifery knowledge and skills complements the obstetric care a woman may require. The desired outcome is that women can still feel in control even if the birth experience is not what they had hoped (Fahy and Hastie 2008). The role of the woman within the team is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2: ‘Team working’.

Judicious use of midwifery skills and knowledge is vital, ensuring that clinical skills have been appropriately employed throughout to support the midwife in her accountability; utilising what is known about physiology and the individual women and having confidence in the woman’s ability to birth. Being a watchful guardian with honed clinical skills and the knowledge to be able to use all that information is what makes the midwife who she is. There is no place for routine and ritual, without justification. Doing things just because we have always done them is not good enough, but doing the right things with the woman’s understanding and consent, even if that means something the woman may prefer to avoid, is good practice of an educated midwife.

Judicious use of midwifery skills and knowledge is vital, ensuring that clinical skills have been appropriately employed throughout to support the midwife in her accountability; utilising what is known about physiology and the individual women and having confidence in the woman’s ability to birth. Being a watchful guardian with honed clinical skills and the knowledge to be able to use all that information is what makes the midwife who she is. There is no place for routine and ritual, without justification. Doing things just because we have always done them is not good enough, but doing the right things with the woman’s understanding and consent, even if that means something the woman may prefer to avoid, is good practice of an educated midwife.Medical intervention

It is acknowledged that modern Western technology and evidence-based medicine has indis-putably contributed to safer childbirth, reducing maternal and fetal mortality. However it is questionable whether the benevolent aspect of paternalism has gone too far and being at the detriment of women’s autonomy in childbirth (Walsh et al. 2004). It is part of the midwives’ role to keep elements of normality as part of the holistic care for women, for those also needing a doctor and medical intervention. Figure 7.8 illustrates a woman receiving some medical inter- vention, using different positions to help labour progress.

Figure 7.8

Figure 7.8Woman on a birthing ball receiving medical intervention. Source: Reproduced with permission from J. Green.

Meeting the baby

The moment a mother meets her baby has been awaited with anticipation. Women’s expecta-tions will differ greatly, for some there may be fear and sense of responsibility; some may not be intending to be the social parent of the child and maybe facing some very difficult times. (See Chapter 5: ‘Parenthood’, where defining parents is discussed in greater depth). Whatever the situation, this is a moment in the lives of the parents and the newborn that will stay with them both forever. The midwife has an opportunity to assist in making this moment memorable and the most optimal physiologically.Midwives must be alerted to the sudden change of environment for the newborn; a stimulat- ing environment may potentially trigger stress responses in the baby. Very little evidence exists about the emotional status of a newborn, although it is known there is an increase in fetal catecholamines in labour in response to birth (Coad and Dunstall 2011). Providing a gentle transition for the newborn simply seems a logical approach. The benefits of skin-to-skin contact for mother and baby are well recognised (Anderson et al. 2006). Skin-to-skin and gentle han- dling may help to instil a calmness that will stay with the baby in the early weeks. The joy of birth and bonding potential is needed even more if labour has resulted in intervention and an assisted or traumatic birth, for example caesarean section or an instrumental birth.

Third stage management

When discussing the third stage of labour with a woman, it is really important to ensure thatshe understands this can be achieved without intervention as the natural conclusion of a normal uncomplicated labour (Soltani 2008), only separating the baby and the placenta and mem- branes once the baby has been born. Alternatively the third stage can be actively managed by the midwife with uterotonic drugs, clamping and cutting the cord and controlled cord traction. Giving information about the third stage of labour would form part of birth planning and should include discussion about both methods of delivery and the benefits and risks for mother and baby. However, the woman should be aware that this decision does not need to be made until the end of the second stage of labour, with full information of the clinical picture.Where there is a risk of the uterus not contracting to expel the placenta and membranes and achieve haemostasis of the blood vessels at the placental site, or other risk factors for haemor- rhage. The woman should be advised regarding active management of the third stage with uterotonic drugs and controlled cord traction (NICE 2007). By giving a simple explanation of the physiology of the third stage, the woman can make the most appropriate decision for her. Some women have no strong feeling regarding this part of labour, wishing to get it over with as soon as possible allowing them to concentrate on their baby, whilst for others it is extremely important.Midwives should ensure they have the skills for both physiological and managed delivery of the placenta, avoiding mixing elements of the two methods since this may have implications on outcome (Begley et al. 2011). Skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding at this point is a moth- er’s well-deserved reward for her hard work. This helps the mother to be more relaxed and produce the hormonal response to encourage separation of the placenta. Soltani (2008) has shown that gravity too can play its part in helping the placenta to separate and expel from the body. It is suggested the woman should be in an upright position for this part of labour.Birth in water may alter the timing of use of drugs if active management of the placenta is to be employed, with midwives waiting until the woman has exited the pool before starting the process for active management. The reality in practice is that midwives and doctors whilst

157158broadly following the principles of active management do vary in their techniques, and as evidence has emerged to support delaying the clamping and cutting of the cord, to allow full transfusion of blood to the baby, this too has further complicated management (Farrar et al. 2009). Partners or women themselves may want to be involved in the cutting of the umbilical cord, seeing this as a symbolic moment where baby becomes truly independent.

157158broadly following the principles of active management do vary in their techniques, and as evidence has emerged to support delaying the clamping and cutting of the cord, to allow full transfusion of blood to the baby, this too has further complicated management (Farrar et al. 2009). Partners or women themselves may want to be involved in the cutting of the umbilical cord, seeing this as a symbolic moment where baby becomes truly independent. Lotus birth involves physiological delivery of the placenta, but the cord and placenta remain intact until the cord separates naturally from the baby. The placenta may be treated with salt and herbs and is wrapped with the baby following birth. This practice whilst not common is increasingly requested.

Lotus birth involves physiological delivery of the placenta, but the cord and placenta remain intact until the cord separates naturally from the baby. The placenta may be treated with salt and herbs and is wrapped with the baby following birth. This practice whilst not common is increasingly requested.

Other books

Threat by Elena Ash

The Lost Life by Steven Carroll

Beauty in Disguise by Mary Moore

Forever a Lord by Delilah Marvelle

The Zoey Chronicles: Discovery (Vol. 2) by Gray, Sophia

La soledad de la reina by Pilar Eyre

The Shallows by Nicholas Carr

Mortlock by Jon Mayhew

The Seat Beside Me by Nancy Moser

Werelord Thal: A Renaissance Werewolf Tale by Tracy Falbe