OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide (25 page)

Read OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide Online

Authors: Chris Seibold

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Operating Systems / Macintosh

When you first boot a new Mac and set up a user, the system is

configured to automatically log in that user. That’s probably fine if you’re

the only person who uses that computer, but not so great if your Mac is

sitting out where a lot of people have access to it. You’ll want to

customize your security settings to fit the environment where you’ll be

using your Mac. If it’s a desktop machine and you’ll be using it only at

home, for example, you probably don’t have much to worry about. But if it’s

a MacBook that you plan on hauling everywhere you go, you’ll want a little

more security.

See

Logging In

to find out how to disable

automatic login, and see

Logging Out, Sleeping, and Shutting Down

to customize your

logout options.

Security in OS X usually comes down to passwords: passwords for

services, accounts, websites, and email. Once you’ve created all those pesky

but necessary passwords, you’ll want to turn your attention to managing

them.

To manage all your passwords, Mountain Lion uses keychains;

they’re where it stores your passwords and certificates to keep them safe

from prying eyes. These keychains save you a lot of time, because your Mac

can use the stored passwords to do a variety of useful things, like

joining your wireless network without any help from you.

The more you do online, the more passwords you need. Ideally, you

want different passwords for everything; using the same password for your

bank’s website and for posting to a third-rate message board isn’t the

best idea. However, with so many passwords running around, it is easy to

forget them. We’ve all been faced with the situation where we were

sure

we typed in the right password, only to be

repeatedly denied access. Fortunately, OS X can help.

So you’ve forgotten the password to some rarely visited

yet essential server or some network you join only every six months.

Turns out Mountain Lion probably remembered the password

for

you because chances are good that when you

first entered the password, Mountain Lion asked if you wanted it to save

the password, you chose Yes. (The three options are Yes, Never, and Not

Now; since Yes is the default, that’s the option most people choose.) To

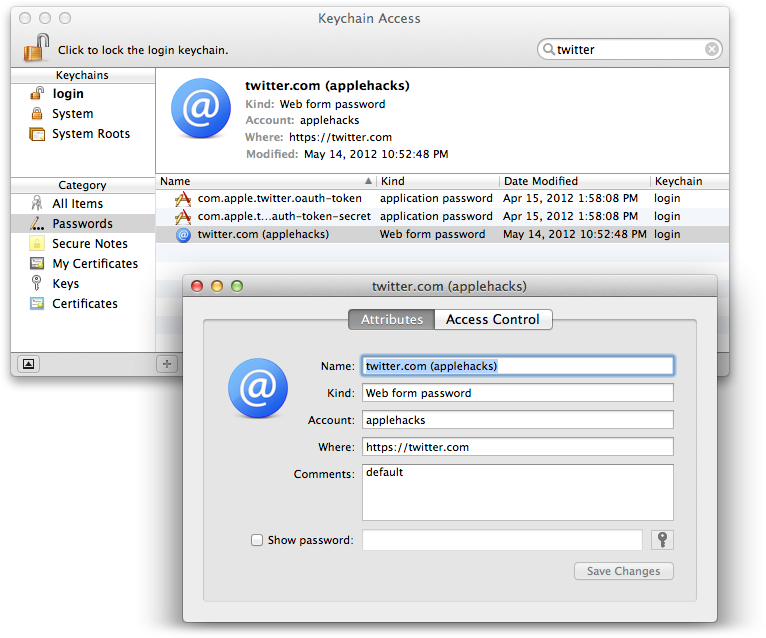

recover the password, open Keychain Access (Applications

→

Utilities

→

Keychain Access) and then type the name of the

site or application, or something else relevant into the program’s

search box. Keychain Access will find entries that match your search

criteria and present you with a list like the one in

Figure 7-1

.

Figure 7-1. Recovering a Twitter password

When whatever you’re looking for appears in the list in the middle

of the Keychain Access window, double-click that item and a window will

pop up that includes a “Show password” checkbox. Check the box, enter

your keychain password (usually, but not necessarily, the same as your

OS X password), and you’ll see the password.

For an added level of security, you can configure OS X to

lock your keychain after a period of inactivity. Open Keychain Access,

click “login” in the Keychains list on the left side of the window, and

then select Edit

→

“Change Settings for

Keychain ‘login.’” You’ll then be able to lock the keychain after a

period of inactivity or when the computer sleeps. Once a keychain is

locked, Mountain Lion won’t let your Mac give out passwords until you

unlock the keychain by typing in your password.

If you work on a Mac managed by someone other than

yourself, you probably don’t want your keychain password to be the

same as your OS X password. Why? Because, if the administrator set

your OS X password for you, that person will also be able to access

the information that’s on your keychain. To change your keychain

password, open Keychain Access, click “login” in the Keychains list on

the left side of the window, and then select Edit

→

“Change Password for Keychain ‘login.’” Enter

a new password and your data will be safe from everyone but

you.

The following passwords are not acceptable:

letmein

,

password

,

123

, and

qwerty

. Using one of

those for anything you care about is like leaving the door to your house

wide open—but removing the welcome mat. Sure, a miscreant

might

pause momentarily when he notices the mat is

missing, but that won’t stop him from coming into your house. You need a

better password.

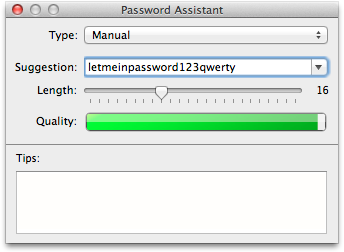

Mountain Lion can help you in your quest. You can find out

whether your chosen password is strong with Password Assistant, which

tests password strength. For whatever reason, you can’t access Password

Assistant directly—you have to use Keychain Access to get to it.

(Actually, any prompt that displays the little key icon will give you

access to Password Assistant, but Keychain Access is one of the easiest

ways to get there.) Open Keychain Access (Applications

→

Utilities

→

Keychain Access), and then select Edit

→

“Change Password for Keychain ‘[keychain

name].’”

In the dialog box that pops up, type a prospective password in the

New Password field. As you type, you’ll see a colored bar appear that

indicates how good your password is (red for weak, yellow for fair, and

green for good or excellent). Under that is a Password Strength rating

(Weak, Fair, Good, or Excellent). When you’re done typing, click the key

icon and the Password Assistant window appears (

Figure 7-2

).

Figure 7-2. Know your password’s strength

If your password isn’t the digital equivalent of Fort Knox, try

out some new passwords in the Password Assistant window to see how they

rate. If you can’t come up with a good one on your own, Mountain Lion is

happy to pitch in and help. The Password Assistant window’s Tips field

gives you pointers on how to build a better password, and the Type

drop-down menu lets you choose the kinds of passwords Mountain Lion

suggests: “memorable” ones, ones with letters and numbers, purely

numeric ones, random ones, or FIPS 181–compliant ones (the kind used by

government agencies).

Once you’ve found a good, strong password, close the Password

Assistant window and then click Cancel in the “Enter a new password

for...” window (unless you actually want to change the password for that

keychain). Now you can type that password into whatever program or

website needs it and know that your info should be pretty

secure.

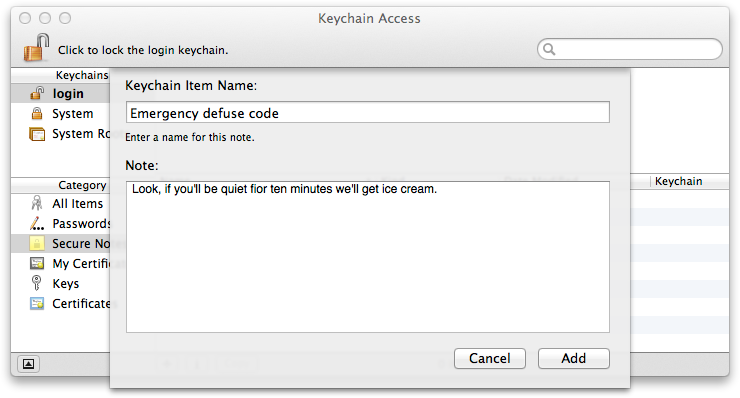

Keychain is great at storing passwords, but you can also

use it to store notes. To write a note that no one else can see (well,

except for people who know your OS X username and password), open

Keychain Access, click “login” in the Keychains list, select Secure

Notes in the Category section, and then click the + button at the bottom

of the window. Give your secret note a name, and then start typing away

(

Figure 7-3

). When you’re done, click Add

and your note will be safely stored in that Keychain.

Figure 7-3. They must never know

With all the goodness Keychain Access offers, you might

want easy access to it. You can add it to your Dock, but that might be

getting a little crowded, and the Keychain icon isn’t the best-looking

one Apple has churned out. Luckily, you can add a menu extra for

Keychain Access (see

Menu extras

for a refresher). To

do that, the next time you’re using Keychain Access, go to Preferences

(⌘-,) and, on the General tab, check the box next to “Show keychain

status in menu bar.”

Carefully choosing passwords is a great start when it

comes to security, but it’s not a perfect solution. If someone has

physical access to your Mac, there are things she can do to get at your

data. If this prospect seems particularly loathsome to you, consider

making the extra effort to enable FileVault, a feature of Mountain Lion

that makes your data impossible to access unless you want it accessed.

For information on setting up FileVault, see

FileVault tab

.

When you’re using the keyboard, you want to keep your hands on the

keys. A trip to the trackpad, reaching for the mouse, or hunting for a

special character can really slow you down. The good news is that Mountain

Lion has a lot of key commands and special characters built right in. The

bad news is that, unless you’re one of those people who memorize the digits

of pi to a thousand places for fun, you won’t remember them all.

The most important key commands and special characters vary from user

to user. For example, if you’re writing about Exposé, knowing how to type é

really helps, but knowing how to type ¬ isn’t of much use. Everyone uses his

or her Mac a little differently, so this chapter features a wide selection

of keyboard commands and ways to type different characters. Memorize the

ones for the functions you use most, and you’ll save a lot of time and

effort.

When your hands are on the keyboard, it’s much quicker to

keep them there to perform some mundane task than it is to dig through the

menus and find the option that lets you type a special character or create

a new folder.

In general, the less time you spend using the mouse (or trackpad),

the more productive you’ll be. While you’ll want to learn the keyboard

commands for all your favorite programs, some commands are so common that

it’s worth reserving a special spot for them in your brain:

- ⌘-S

Save. This saves the document you’re working on. The

more often you use this command, the happier you’ll be (at least

until OS X’s Auto Save feature is part of every program). Nothing is

more frustrating than having all your hard work disappear when the

power flickers or an application crashes.NoteIf you’re using a keyboard designed for Windows

systems, you won’t see the ⌘ key. Instead, use the Windows key,

which is usually in the same spot you’d find the ⌘ key. Some

keyboards use a different symbol, however; for example, the Happy

Hacking Keyboard uses the “lozenge” symbol (◊).- ⌘-C

Copy. This command copies the current selection for

later pasting.- ⌘-X

Cut. This command deletes the current selection but

copies it to your Mac’s memory. After you’ve cut something, you can

paste it elsewhere (until you copy or cut something else, that

is).- ⌘-V

Paste. Once you’ve copied or cut something, you’ll

want to paste it.- ⌘-,

Opens the preferences for the active

application.- ⌘-] and ⌘-[

Moves forward (]) or backward ([) in the Finder,

Safari, and some other applications. For example, when navigating to

various directories in the Finder, you can use these keys instead of

clicking the arrows in the upper-right corner of the window.- ⌘-Shift-?

Opens the current application’s Help dialog box so you

can get quick answers to your vexing questions.- ⌘-Q

Quits the current application.

NoteYou can’t easily quit the Finder, so this command doesn’t

work when you’re using it. To find out how to quit the Finder (or

more accurately, relaunch it), see

The Finder stops responding

.- ⌘-Tab

Brings up the Application Switcher, which lets you

cycle through running applications by pressing Tab repeatedly as you

hold down ⌘. When you get to the application you’re after, let go of

both keys. If your hands are on the keyboard, this is a

much

faster way to switch applications than the

Dock.- Option-⌘-Esc

Force quits the current program.

Once you’ve mastered those commands, your appetite for keyboard

shortcuts is likely to become insatiable. Fortunately, there’s plenty more

of that keyboard-shortcut, time-saving goodness, much of which is shown in

Table 8-1

.

Unfortunately, some of these commands don’t work the same

way in all programs. For example, in the Finder and many other

applications, ⌘-I displays the Get Info window for the currently

selected file or object, but in most word-processing applications, ⌘-I

italicizes the selected text.

Also, on some keyboards, you may need to hold down the key labeled

Fn to use keyboard shortcuts that require a function key (F1, F2,

etc.).

Table 8-1. Common keyboard shortcuts

Key | Most common | Finder |

|---|---|---|

⌘-A | Selects all | Selects all items in |

⌘-B | Makes selected text bold | None |

⌘-C | Copies current | Copies selected files and |

⌘-D | Duplicates selected object | Duplicates selected file or |

⌘-E | Searches for highlighted | Ejects disk |

⌘-F | Finds text | Opens a new Finder window |

⌘-H | Hides current | Hides Finder |

⌘-I | Italicizes selected | Opens Get Info window for |

⌘-J | Jumps to currently selected | Shows View |

⌘-K | Clears screen (Terminal) or | Opens “Connect to Server” |

⌘-L | Opens dialog box that lets | Creates an |

⌘-M | Minimizes | Minimizes |

⌘-N | Creates new | Opens new Finder |

⌘-O | Displays Open File dialog | Opens selected |

⌘-P | Prints | None |

⌘-Q | Quits current | None |

⌘-R | Varies | Shows original file when an |

⌘-S | Saves current | None |

⌘-T | Displays Font | Adds selected item to |

⌘-V | Pastes copied | Pastes copied file(s) or |

⌘-W | Closes | Closes |

⌘-X | Cuts | None |

⌘-Z | Undoes most recent | Undoes most recent |

⌘-1 | Varies | Displays Finder items as |

⌘-2 | Varies | Displays Finder items as |

⌘-3 | Varies | Displays Finder items as |

⌘-4 | Varies | Displays Finder items in |

⌘-Delete | Varies | Moves selected item to |

⌘-Tab | Opens Application | Opens Application |

⌘-[ | Goes back one page (in web | Goes back one |

⌘-] | Goes forward one page (in | Goes forward one |

⌘-? | Activates Help | Activates Help |

⌘-space bar | Activates Spotlight | Activates Spotlight |

⌘-' | Cycles through application | Cycles through Finder |

Tab | Moves focus to next item or | Moves focus to next |

Shift-⌘-3 | Takes a picture of your | Takes a picture of your |

Shift-⌘-4 | Displays a cursor for | Displays a cursor for |

Shift-Control-⌘-3 | Works like ⌘-Shift-3, but | Works like ⌘-Shift-3, but |

Shift-Control-⌘-4 | Works like ⌘-Shift-4, but | Works like ⌘-Shift-4, but |

Shift-⌘-A | Varies | Opens Applications |

Shift-⌘-C | Varies | Opens Computer |

Shift-⌘-D | Varies | Opens Desktop |

Shift-⌘-O | Varies | Opens Documents |

Shift-⌘-G | Varies | Opens “Go to the folder” |

Shift-⌘-H | Varies | Opens Home |

Shift-⌘-K | Varies | Opens Network |

Shift-⌘-N | Varies | Creates a new |

Shift-⌘-Q | Displays logout dialog box, | Displays logout dialog box, |

Shift-⌘-S | Opens “Save As...” dialog | None |

Shift-⌘-U | Varies | Opens Utilities |

Shift-⌘-Delete | Varies | Opens Empty Trash dialog |

Shift-Option-⌘-Delete | Varies | Empties |

Option (while dragging) | Copies item to new | Copies file/folder to new |

⌘-Option (while dragging) | Varies | Creates an alias to a |

Option-⌘-D | Shows/hides the | Shows/hides the |

Option-⌘-M | Varies | Minimizes all |

Option-⌘-Esc | Opens a dialog box that | Opens a dialog box that |

Option-⌘-Eject | Puts computer to | Puts computer to |

Control-Eject | Displays the | Displays the |

Control-⌘-Eject | Quits all applications and | Quits all applications and |

You’re probably not going to remember

all

those

shortcuts, but you’ll likely remember the ones you use frequently. And

more time at the keyboard means less time wasted mousing and searching for

commands.

If you don’t like the key commands built into OS X, you

don’t have to put up with them. You can change them or add your own by

taking a trip to the Keyboard preference pane. For details, see

Keyboard

.

If you’re banging away on the keyboard and find yourself

wanting to type special characters (like the é in Exposé, for example),

there are convoluted methods of getting the character you want (pasting

them from the Web, say). But you might be wondering if there’s a

trackpadless or mouse-free way to do it. Fortunately, there is.

In OS X Lion, Apple added an easy way to get at those pesky

diacritical symbols. Simply type the letter you’re interested in and

hold the key down

; a window will pop up with all your

options (as in

Figure 8-1

). You can then

use the arrow keys to select the diacritic, click the one you want, or

press the number key that corresponds to the number below your

pick.

Figure 8-1. All your options for e

This feature is universal, so you can use it anywhere you can type a

character. It does have a couple of drawbacks, though: depending on how

your key repeat rate is set (see

Keyboard

), you might

find yourself typing

sss

before the diacritic menu

shows up; and if you type a special character often, it’s faster to commit

its keyboard shortcut to memory instead.

Table 8-2

shows how to easily type

diacritical symbols.

Table 8-2. Diacritical accent mark shortcuts

Symbol | Name | Keystroke |

|---|---|---|

´ | Acute | Option-E, then type the |

^ | Circumflex | Option-I, then type the |

` | Grave | Option-`, then type the |

˜ | Tilde | Option-N, then type the |

¨ | Umlaut | Option-U, then type the |

That takes care of only a few characters you may not be able to find

on your keyboard. But what about other characters, such as the euro symbol

or the Apple logo? You might try looking through the Font Book utility,

but with the number of fonts included in a standard OS X install, that

task can require more luck than skill.

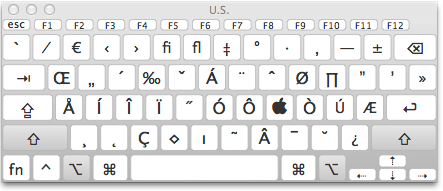

The Character Palette is a bit easier to use. You enable it by

heading to →

→

System

Preferences

→

Language & Text. Click the

Input Sources tab, and then check the box labeled Keyboard & Character

Viewer. Your Mac adds a new icon to the menu bar that lets you launch

either Character Viewer or Keyboard Viewer. Character Viewer lets you

browse a wide variety of special characters and insert them into documents

by clicking them (the characters appear in the most recently used

application). With Keyboard Viewer (

Figure 8-2

), you can hold down

Shift, Option, or Shift

and

Option simultaneously to

see how the keyboard is modified when you’re depressing those modifier

keys. As with Character Viewer, simply click a letter or a symbol to

insert it into a text field.

Figure 8-2. Wonder what Option-Shift does to the characters on your keyboard?

Wonder no more!

You can also check out

Table 8-3

for a quick

reference to U.S. English keyboard modifiers.

Table 8-3. Special character shortcuts for U.S. English keyboards

No | Shift | Option | Shift-Option |

|---|---|---|---|

` | ˜ | ` | ` |

1 | ! | ¡ | ∕ (fraction slash |

2 | @ | ™ | ₠ |

3 | # | £ | ‹ |

4 | $ | ¢ | › |

5 | % | ∞ | fi (ligature) |

6 | ^ | § | fl (ligature) |

7 | & | ¶ | ‡ |

8 | * | • | ° |

9 | ( | ª | · |

0 | ) | º | ¸ |

- | _ | – | — |

= | + | ≠ | ± |

q | Q | Π| Π|

w | W | Σ | „ |

e | E | ´ (above next vowel | ´ |

r | R | ® | ‰ |

t | T | † | ˇ |

y | Y | ¥ | Á |

u | U | ¨ (above next vowel | ¨ |

i | I | ^ (above next vowel | ^ |

o | O | Ø | Ø |

p | P | Π | ∏ |

[ | { | “ | “ |

] | } | ‘ | ‘ |

\ | | | « | » |

a | A | Å | Å |

s | S | ß | Í |

d | D | ∂ | Î |

f | F | ƒ | Ï |

g | G | © | ″ |

h | H | ˙ | Ó |

j | J | Δ | Ô |

k | K | ˚ |

|

l | L | ¬ | Ò |

; | : | ... | Ú |

‘ | “ | Æ | Æ |

z | Z | Ω | ¸ |

x | X | ≈ | ˛ |

c | C | Ç | Ç |

v | V | √ | ◊ |

b | B | ∫ | I |

n | N | ~ | ˜ |

m | M | µ | Â |

‚ | < | ≤ | ¯ |

. | > | ≥ | ˘ |

/ | ? | ÷ | ¿ |