OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide (20 page)

Read OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide Online

Authors: Chris Seibold

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Operating Systems / Macintosh

The Startup Disk pane lets you specify which currently

attached disk you wish to use to start your Mac. You can use any valid

startup disk (your choices will show up in the pane), including DVDs and

external disks. Clicking Restart reboots your system using the selected

disk. (You can also choose a startup disk by pressing and holding the

Option key while your Mac is starting).

If your Mac has a FireWire port, you can also choose to

start the machine in Target Disk Mode. This turns your high-priced Mac

into a glorified hard drive, but it is extremely useful for transferring

data and preferences and repairing troublesome hard disks.

After you install a non-Apple application that has a

preference pane of its own, you’ll see that pane in a new section of

System Preferences labeled Others. These panes work the same as Apple’s

own—they let you control aspects of the program or feature you added. For

example, if you install Perian (

www.perian.org

) so your Mac

can display a greater variety of video types, you can adjust Perian via

its preference pane.

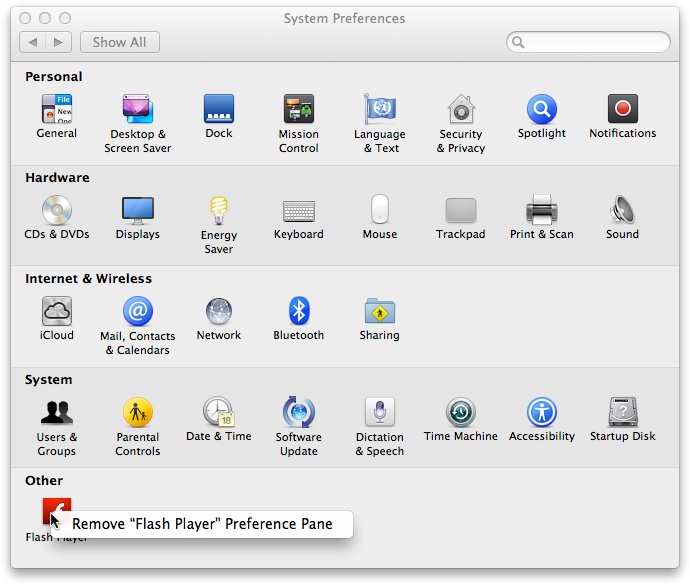

One of the most common questions about third-party preference panes

isn’t how to

use

them; it’s how to get rid of them.

If the third-party application doesn’t include an option to uninstall its

preference pane, you can manually uninstall the pane by right-clicking or

Control-clicking it and then selecting Remove (see

Figure 5-8

).

Figure 5-8. Removing an unwanted preference pane

Removing an application’s preference pane removes only the

preference pane, not the application itself.

When you install Mountain Lion, a number of applications and utilities

come along for the ride. You get the predictable apps like Safari, and the

boring-yet-useful utilities like Activity Monitor, as well as brand-new

applications like Reminders. And some of the older applications have been

radically upgraded (and, in the case of iChat, renamed; it’s now called

Messages).

This section gives you a quick rundown of all the applications

installed by default with Mountain Lion. Note that the list covers only

applications that come with a Mountain Lion install—if you have a

brand-new Mac or are upgrading an older Mac, you’ll likely have other

applications that aren’t included in this list (such as iLife).

The App Store application is Apple’s electronic

distribution client. If you’ve used an iOS device or any version of OS X

after 10.6.7, you’re familiar with the concept. If you haven’t used the

App Store before, it works like you might expect: When you launch this

app, you’ll see a store where you can buy a huge variety of apps. The

App Store offers recommendations, shows you what’s popular, and offers a

search function so you can find the perfect app. Once you’ve made a

selection (or several), you type in your iTunes or iCloud password and

purchase the chosen app(s).

Worried that you could lose the apps you’ve bought if

your computer crashes? Never fear: once you buy an app, you can

download it as many times as you like.

Using the Mac App Store differs from the traditional way

you’re used to managing software. Instead of having to search for

updates, you’ll find any updates to your purchases prominently indicated

in the App Store and in the Notification Center; click Update All to

install the latest versions of all your purchases. You can install App

Store purchases on any of your authorized Macs (up to five).

You can’t authorize or deauthorize machines via the Mac

App Store. Instead, you have to open iTunes, head up to the Store

menu, and then manage your Macs from there using the

Authorize/Deauthorize This Computer commands.

Automator is a workflow tool for automating repetitive

tasks: resizing photos, converting files to different types, combining

text files, syncing files between folders—that kind of thing. In

Mountain Lion, Automator looks and acts much like previous versions, and

at first glance you won’t notice the difference. But closer inspection

reveals new actions that make automating things even easier. So if there

was something you couldn’t get Automator to do before, now is a great

time to revisit this application. Automator supports Auto Save and

Versions (see

Auto Save and Versions

).

Still not finding the script you need? Google has you

covered: head to

Google.com

and type

“automator actions” into the search box, and you’ll find scads of

prewritten scripts.

When you fire up this application, you get a basic

calculator. If you explore the program’s menu bar, you’ll note that it

has scientific and programmer modes (in the View menu), and numerous

conversion functions (in the Convert menu). If you want a history of

your calculations, you can get a running record by using Paper Tape

(⌘-T). Calculator can also speak: the program can announce both button

presses and your results; just visit the Speech menu in Calculator’s

menu bar.

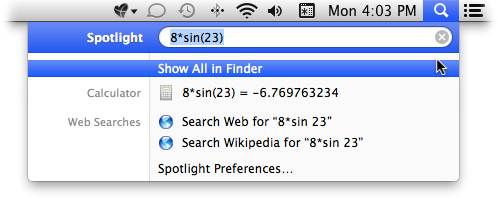

Using Calculator for basic math isn’t the fastest way to

get the answer—Spotlight can do math, too. So if you need a simple

expression calculated, type it into Spotlight (see

Figure 6-1

) and skip

Calculator altogether!

Figure 6-1. The same answer as Calculator, but much more convenient

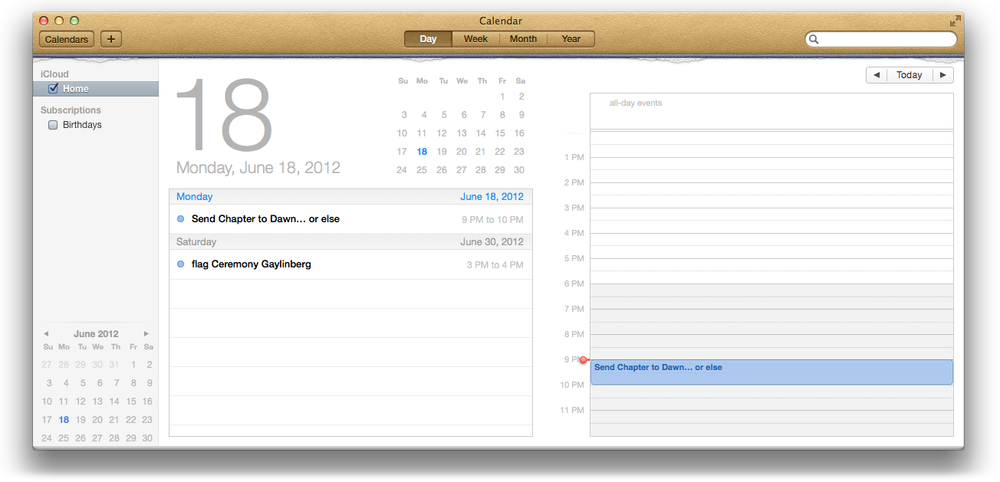

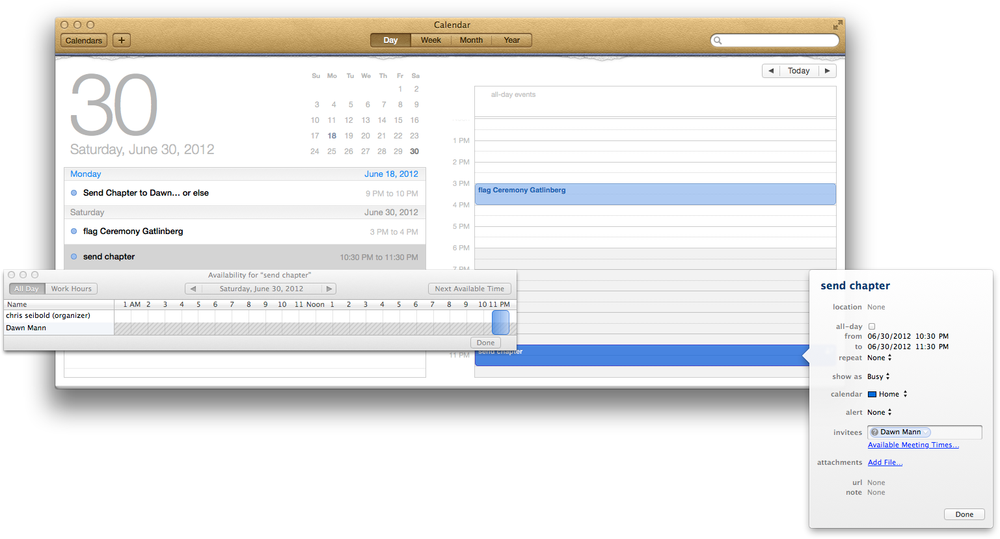

In earlier versions of OS X your calendaring needs were

handled by iCal. You won’t find iCal in Mountain Lion because it’s been

replaced by Calendar. Like iCal, Calendar’s interface resembles a

desktop calendar, but the program’s look is more refined than it was in

Lion (see

Figure 6-2

).

Calendar also adds some features not found in the last version of iCal,

like a sidebar (click the Calendars button to display it).

Figure 6-2. Rejoice, iCal fans—the sidebar has returned!

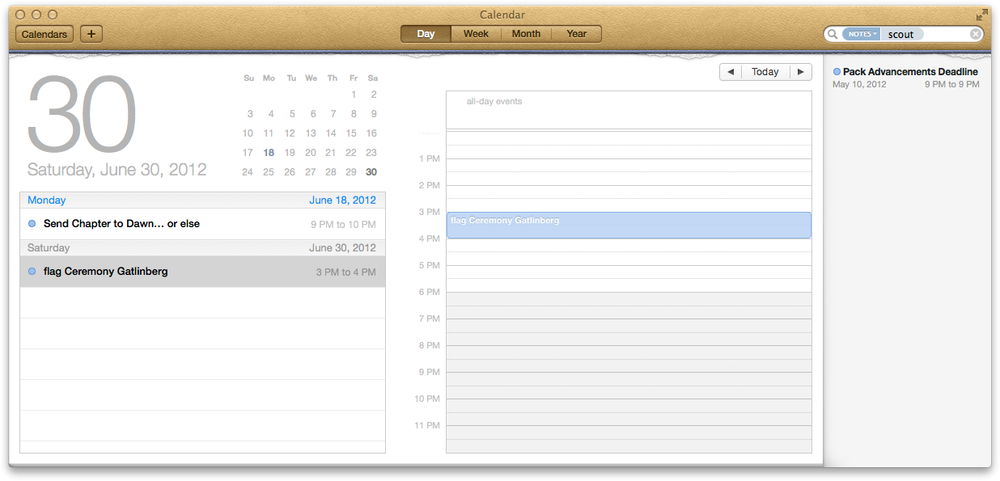

Calendar also adds a new method for searching through all

your calendar entries:

search tokens

. Search tokens

make searching easier. Start typing whatever you’re looking for and a

list will drop down. When you see what you want, select it from the

drop-down menu. The options will be something like the following:

- Event contains “scout”

Title Scout

- Notes

Scout

Select Scout under Notes and it’ll transform into a token. For

example, if you search for “Scout” (

Figure 6-3

) and then select “Scout” under

Notes, the calendar is filtered so only entries with “Scout” in their

notes show up. You don’t have to stop with one token; you can keep

adding tokens to find exactly what you want. Search tokens have been

around in OS X for some time, but their use is becoming more widespread.

For example, you’ll now find search tokens in Mail, too.

Figure 6-3. Searching Calendar entries

Calendar retains iCal’s Quick Event feature—simply click

the + button to create an event just by typing the date and time. If

your event needs more info than just the day and time, then click the

entry and a pop up window will allow you to add alerts, invitees,

locations, and so forth (

Figure 6-4

). If you’re subscribed to

the invitee’s calendar, then clicking Available Meeting Times will

reveal any conflicts in your calendar or theirs.

Figure 6-4. Inviting an editor to an event

Mountain Lion features an updated version of Chess. As in

earlier versions, you get the standard human-versus-computer chess game,

as well as four chess variants, a tweakable board and pieces, and the

ability to speak to your Mac to move pieces. (If you don’t like the

default view, you can change the tilt of the chessboard by clicking and

holding the mouse button anywhere on the board’s border; arrows will

appear that allow you to tilt and rotate the board to your

liking.)

One difference from previous versions is that the difficulty

slider has changed (go to Chess

→

Preferences to see it). In earlier versions,

you just moved the slider to the point where you thought you could beat

the computer and then hoped for the best. In this version, the slider is

much more informative—it tells you exactly what the computer is doing

(

Figure 6-5

).

Figure 6-5. You’re about to get dominated by your Mac

You can also pit the computer against itself or play

against another human. Sadly, you can’t play chess against someone over

a network, so if you want a head-on challenge with a human, they’ll have

to be at your Mac with you. And if you’re suddenly called away from your

Mac during a heated game, don’t worry—this version of Chess features

Auto Save, so you don’t have to worry about losing any progress.

The biggest change in Chess? It’s included in Game Center (see

Game Center

), which means your Fisher-esque chess

skills will be rewarded with badges!

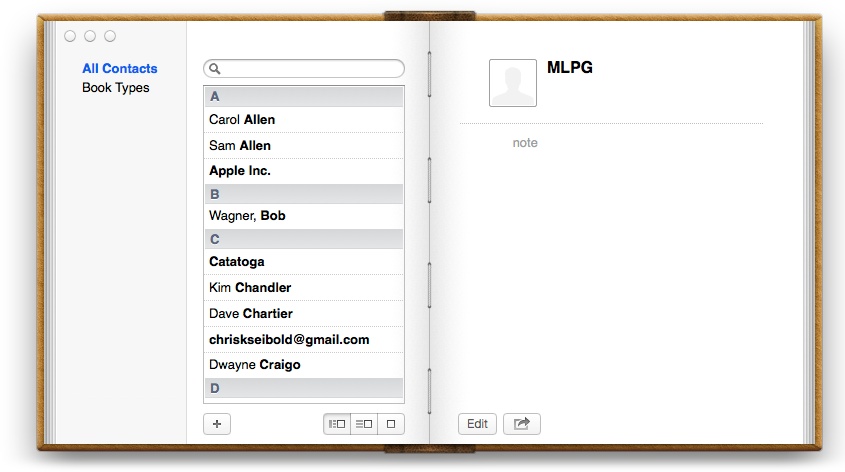

If you look for Address Book in Mountain Lion, you won’t

find it. The functionality isn’t lost, though—the app has been renamed

Contacts. But the name isn’t the only thing that changed; Contacts

includes some upgrades compared with Address Book. For one thing, the

three-column layout makes a return after being banished in Lion so you

won’t have to click that annoying bookmark to flip between individuals

and groups of contacts (see

Figure 6-6

).

Figure 6-6. The third column for groups is back!

Contacts also features a Share Sheet button so you can

easily share a contact via email, Messages, or Air Drop. Like previous

versions of Address Book, Contacts stores information in iCloud so if

you add or delete a contact on one of your Apple devices, that change

shows up on all of them.

When you set up your Mac, Contacts automatically adds an entry

for you. That might seem crazy—after all, you know how to get in touch

with yourself—but there are benefits. For example, you can hit the

Share Sheet button in Contacts to easily share your contact info with

anyone you wish.