OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide (4 page)

Read OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide Online

Authors: Chris Seibold

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Operating Systems / Macintosh

Before Migration Assistant came along, getting your data onto your

new Mac could be a real pain. While Migration Assistant is a fantastic

tool, it has one drawback: it doesn’t differentiate between different

types of networks.

As you know, not every network connection is equal. If you’re

transferring small bits of information (like email or text messages), a

cellphone protocol is plenty of bandwidth. But when you’re transferring

larger chunks of data, the connection type is more important. If you’re

using Migration Assistant, there’s a good chance that you’re planning to

send a bunch of data from your old computer to your new Mac, so the

speed of the transfer really matters—especially since you’ll be locked

out of both machines for the duration of the transfer.

Here are your data-transfer options from fastest to

slowest:

- Thunderbolt

You couldn’t use Thunderbolt when Lion was released,

not because some Macs didn’t have the port for it, but because

there wasn’t a cable available from Apple. Now you can get the

required cable from Apple for $49. It’s an investment you might

want to make if you have a lot of data to transfer, because

Thunderbolt can transfer data at up to 20 gigabits per

second.- Ethernet

Ethernet is your second-fastest option. If your Mac

has an Ethernet port (all Macs except the MacBook Air do), you can

string an Ethernet cable between your old computer and your new

Mac and transfer data at up to a gigabit per second.- FireWire 800

FireWire 800 is your next-fastest option. Not every

Mac that can run Mountain Lion has a FireWire 800 port, so if

you’re unsure, check your System Information (see

System Information

) and select FireWire. If both your

computers are FireWire 800 equipped, you’ll be swapping data at a

peppy 800 Mbps. A lot of Mac owners have FireWire

400

on their old machines and FireWire

800

on their new ones (no new Macs have

FireWire 400). If you’re in that camp, you can get a FireWire 400

to 800 cable (try Amazon) and then transfer your files using a 400

Mbps connection.- WiFi

WiFi is the slowest option. Its speed varies

depending on the network, but if you’re using the 802.11n, your

network could be running up to 300 MBps.

The speeds listed above are best-case scenarios, so your real-life

experience may not match those numbers. But even with that caveat,

you’ll save a significant amount of time if you use one of the wired

options instead of WiFi.

Your Mac is kind of lazy. It doesn’t care which transfer method

is the fastest; it’ll automatically opt for the network connection

you’re currently using. So if you don’t want to sling files over your

WiFi connection (which could take forever), you can string a

Thunderbolt cable between your Macs and then switch to

that

connection

in the Network preference pane to get your data moving at breakneck

speed.

If you’re migrating data, chances are you have a new Mac.

If you’re like most people, you’ve accumulated a lot of cruft over time,

and you might not want to transfer

everything

from

your old Mac. Of course you’ll want to save that folder of lolcat

pictures, but that folder with your master’s thesis is just taking up

space.

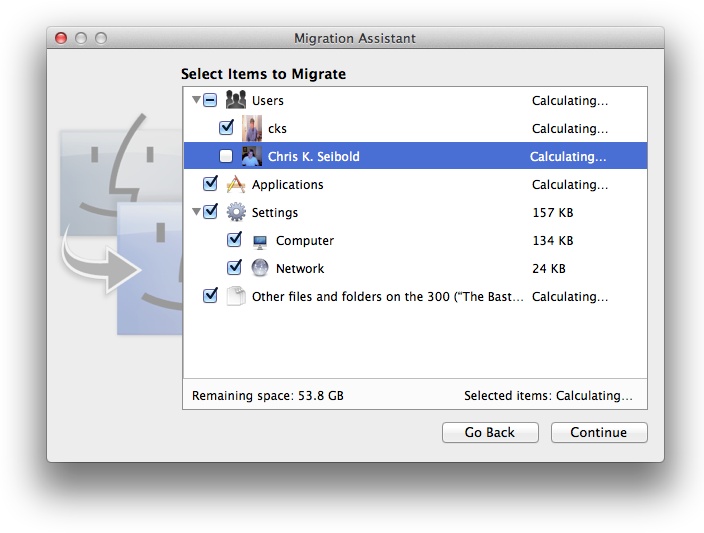

Migration Assistant lets you decide what to take and what to leave

behind in terms of users and settings. (Don’t worry: this is a

nondestructive process, so the data you shun on your new Mac will still

be on the old machine.) Simply follow the data-migration process

described earlier in this chapter, but when you get to the “Select Items

to Migrate” screen (

Figure 2-6

),

uncheck the items you want to leave behind. Click the disclosure

triangle to display all your options.

Figure 2-6. Choosing what data to grab

Don’t get confused by the folder names listed on the “Select

Items to Migrate” screen. For example, Movies doesn’t mean that

Migration Assistant will import all your movie files, just that it

will import the Movies

folder

. If you have movies

stored elsewhere and you want them to come along during the transfer,

make sure the “All other files and folders” option is checked.

After you make your selections, click Continue and your data will

be transferred. Give it some time and the data will magically appear on

your new Mac.

Once Migration Assistant finishes transferring your data, Setup

Assistant will pop up and offer to upgrade your email (if you’re

migrating from an older version of Mac OS X). This takes a few moments,

but once it’s finished, you’re free to use your new Mac and pick up

where you left off with your old machine!

Finding your way around Mountain Lion for the first time is

exciting, but it’s also easy to miss many of the cool new features,

especially if you’re new to OS X or you’ve been using an older version of

it. This chapter will get you up to speed on the basics of OS X, with a

special focus on what’s new in Mountain Lion. It’ll familiarize you with

the key aspects of OS X so you can get the most out of Apple’s best

operating system to date.

The logical place to start is with the first thing you

created when you installed or ran OS X for the first time: your account.

Mountain Lion’s roots go all the way to Unix, a multiuser workstation

and server operating system. Because OS X is based on Unix, it’s also

multiuser to its core. Even if no one but you ever touches your Mac,

it’s still helpful to understand user accounts, because you may need to

deal with them someday.

Consider these situations:

As you’ll learn shortly, you may want to set up an

unprivileged account for day-to-day use to limit your vulnerability

to mistakes and malicious software.If you ever need to run a demonstration on your Mac, you’ll

probably want to create a separate account to run the demo to

prevent interruptions from chat buddies, calendar reminders, and the

like.Even the most solitary Mac user eventually needs to let

someone else use her Mac (a houseguest, a family member, or a TSA

agent), and it’s so easy to set up a new user account that you may

as well do it. Then even your most reckless friend can use your Mac

without much threat of major chaos.

There are six types of user accounts in OS X, and you can

also create groups of users:

- Administrator

When you create your first account in OS X, it’ll

automatically be an Administrator account. This is the most

powerful type, because an administrator can make

global

changes that affect the computer and

all other user accounts, like adding and removing programs.

Because of this ability to change things (sometimes

inadvertently), most savvy Mac users argue that you shouldn’t use

Administrator accounts for day-to-day computing; instead, they

recommend using a Standard account most of the time.NoteYou might detest the idea of jettisoning the power of the

Administrator account for day-to-day use. But even if you’re

using a Standard account, you can still make global changes by

typing in your Administrator account name and

password.- Standard

Standard accounts are the sweet spot: you can’t mess

up your Mac or anyone else’s account while using a Standard

account, but you still have plenty of control over how your Mac

works. You can add and delete programs for just your account, but

not to the entire system, and you can delete files you own

(meaning ones you’ve created or installed), but not files owned by

others.- Managed with Parental Controls

Accounts managed with Parental Controls are limited

in what they can do. These users can’t make changes to the system

at all. If you tried to use a managed account, you’d likely find

it frustrating and unacceptable; but to a five-year-old, a managed

account is nirvana. You can adjust the settings using the Parental

Controls preference pane (see

Parental Controls

).- Sharing Only

Sharing Only accounts are designed to let people

connect to your machine from another computer to share files.

People assigned this type of account can’t log into your Mac via

the login screen; only remote connections are accepted.- Group

You can use Group accounts to create a collection of

multiple users. These types of accounts let you exercise

fine-grained control over privileges for shared documents.- Guest

If you want to let others use your Mac without the

ability to accidently delete precious files or install malicious

software, you can enable the Guest User. This creates an option on

the login screen to log in as, unsurprisingly, Guest. There’s no

password required, and you’re free to lock the account down using

Parental Controls. Guests can use your Mac as they wish while

they’re logged in, but the moment they log out, everything they’ve

done (documents they created, emails they’ve sent, etc.) gets

deleted. (Note that the Guest Account

isn’t

an option if you have FileVault activated; see

FileVault tab

.)

Now that you know the different types of accounts in

Mountain Lion, you’ll likely want to set up a few. Click →

→

System

Preferences

→

Users & Groups

(located in the System section). Before you can make any changes, you

have to click the lock icon at the bottom left of the preference pane

and then enter an administrator username and password. The extra level

of security is there because this preference pane lets you adjust the

level of access for other accounts, so you wouldn’t want an

unauthorized person making changes.

To add a new account, click the + button above the lock icon.

This opens a drop-down window where you can select the type of account

to create, enter the identifying info (full name, account name), and

set up a password. Mountain Lion assigns a default image as the new

user’s picture. To pick a different image, just click the default

image in the middle of the preference pane. You’ll be able to choose

from the icons included with Mountain Lion or snap a pic with your

Mac’s built-in iSight camera and then apply Photo Booth’s effects to

the image (click the “Apply an effect” button in the snapshot’s lower

right). Setting up an account is significantly more fun in Mountain

Lion than in previous versions of OS X.

To enable the Guest account, click Guest User in the

list of accounts, and then check the box marked “Allow guests to log

in to this computer.” To disable this account, simply uncheck that

same box; this will prevent guests from using your computer without a

password.

The Home folder is what makes your Mac seem like

your

Mac. For example, if you create a document and

save it in Documents, the document doesn’t show up in some centralized

documents folder for the entire system; it shows up in only the

Documents folder that lives inside your Home folder.

This pattern extends to other folders, too (Music, Movies,

Pictures, and so on). Each account you create gets its own Home folder

with a subset of folders inside it. This is where all your files and

personal preferences (like your selected desktop background) are stored.

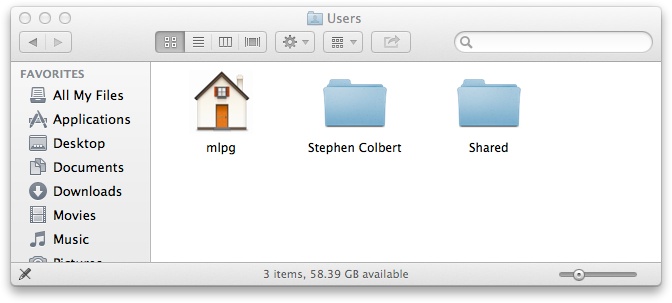

All the home folders are stored in a folder called Users that’s found in

the top level of your drive.

There’s one folder inside the Users folder that doesn’t

correspond to any user: the Shared folder. You can use it to store

files and folders you need to share among users on the same

Mac.

You can access your Home folder by opening a Finder window and

then either clicking the house icon in the sidebar or choosing Go

→

Home (Shift-⌘-H). In every Home folder, you’ll

find the following subfolders:

- Desktop

This is where all the files sitting on your desktop are

stored. (There are a few other types of items that can appear on

the desktop—hard disks, CDs, DVDs, iPods, and servers—but you

won’t see them in this folder.) If you drag a document from this

folder to the Trash, it’ll disappear from your desktop.- Documents

This is where your Mac saves documents by default.

Using this folder isn’t mandatory, but it does offer a level of

convenience to have a central repository for all your documents.

You can add subfolders for even more organization: just open the

Documents folder and then choose File

→

New Folder (Shift-⌘-N).- Downloads

The Downloads folder serves double duty: it lives in your

Home folder and has a spot in your Dock. Anything you download

from the Web via a browser shows up here (unless you change the

default download location in your browser’s preferences, that is)

and

in your Dock in the

Downloads stack (the stack bounces when a new item finishes

downloading). If you click the Save button next to an attachment

in Mail, it’s also saved here. You can get your downloaded items

either by opening this folder or by going to the Downloads stack

in the Dock.- Movies

This folder is much like the Documents folder, only

it stores all the movies you make with iMovie and screencasts you

make with QuickTime Player. Just as with the Documents folder,

there’s no reason to store your movies here other than

convenience.- Music

The Music folder, not surprisingly, is where you can

store music files. It’s also where iTunes stores its music library

and any iTunes purchases you make, including iPhone/iPod apps and

videos.- Pictures

Toss all your

.jpg

,

.png

, and

.gif

files right in here. iPhoto also

uses this folder to store images you add to iPhoto.- Public

The Public folder is a repository for files you want

to share with other users who can log into your Mac. You can get

to another user’s Public folder by switching to the Finder and

choosing Go

→

Computer. You’ll see a

window showing all the drives and networks coupled to the Mac

you’re using. Selecting the startup drive will reveal a folder

called Users. Open that folder, and you’ll see all the other

users’ Home folders (they’re labeled with the respective users’

names, as shown in

Figure 3-1

). Open the

appropriate person’s folder, and you’ll see her Public folder. You

can grab any files stored in another user’s Public folder and use

them as you wish. Likewise, any files you toss into your Public

folder can be grabbed by anyone using the same Mac. (Note that,

while you can copy and modify any files you find in the Public

folder, you can’t actually change the contents of someone else’s

Public folder.) If you want to share files in this folder with

people on

other

computers, you’ll have to go

to the Sharing preference pane (see

Sharing

).

Figure 3-1. This Mac has a meager number of accounts, but even if you

have 100 accounts, they’ll all be stored in the Users

folderTo receive files from others who use the same Mac,

have them put the files in your Drop Box, a folder inside your

Public folder. Drop Box is a shared folder, but the sharing goes

only one way: people can put things into your Drop Box, but they

can’t take anything out. In fact, they can’t even see what’s in

this folder. To use Drop Box, enable File Sharing (see

Sharing

).- Sites

You’ll see this folder only if you’re using an Administrator

account. If you want your Mac to host a website (it’s certainly

capable), then this is where you put the files for the site.

You’ll need to do more than add an HTML file to this folder to get

your site working, though. See

Sharing

to start

sharing sites stored in this folder over your local

network.

Where’s My Library Folder?

Before Mac OS X Lion, there was one additional folder inside the

Home folder: Library. This is where your preferences and settings

(among other things) are stored. If you’re used to manually

controlling various aspects of your Library folder, you’ll likely miss

having easy access to it.

It turns out the Library folder isn’t really gone; it’s just

invisible. The easiest way to make it appear is to head to the Finder

and click the Go menu. With that menu open, press the Option key, and

the Library folder will magically appear as a menu item. Click it and

you can get back to manually messing about with your Library folder if

you’re so inclined (but be warned that tweaking items in the Library

folder can have unintended consequences).