OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide (3 page)

Read OS X Mountain Lion Pocket Guide Online

Authors: Chris Seibold

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Operating Systems / Macintosh

If you look for iChat in Mountain Lion, you won’t find it;

like the dodo, iChat is dead. But just because iChat is gone doesn’t

mean you have to stop chatting. The new Messages app retains all the

functionality of iChat and adds much more. In Messages, you can send

unlimited messages to anyone who uses an Apple device. And even better,

because everything’s instantly synced with iCloud, you can now go

straight from chatting using your

Mac to chatting using your iPhone without a break in the

conversation.

You can send texts from Messages, chat using your Jabber (or other

popular chat program) account, start a FaceTime conversation with your

buddy stationed at the South Pole, and so forth. It’s like Apple has

rolled all your communication needs into one convenient app.

Even better, like iMessage (the iOS app that inspired Messages),

when you’re contacting other Apple-gadget aficionados, you won’t run up

their cellphone bills: texts you send with Messages don’t count against

their cell providers’ text-message limits. (Those message limits still

apply for

non

-Apple cellphones and other devices,

however.)

According to Apple, the most popular portable gaming

device in the world is the iPod Touch. If you spend a lot of time gaming

on your iOS-based device, it stands to reason that you might want to

keep the games going when you’re using your Mac.

You’ve grown to love checking the leaderboards and playing

online friends with your iPad. With the Game Center, you can now play

those same friends when you’re using your Mac. As an added bonus, since

Game Center is included in Notifications, when you’re playing against

your cheating sister, say, you’ll be notified as soon as she makes yet

another cheater move so you can immediately take corrective action. See

Game Center

for more info.

Imagine you’ve got a video or Keynote presentation on your

Mac that you want to share with the world—or at least a group of people

too large to comfortably watch it on your Mac. With AirPlay Mirroring,

you can stream what’s on your screen to an Apple TV. Have a web page you

want to show the entire class? Turn on AirPlay Mirroring, and all your

students can see that page on the big screen. Miss your favorite show

last night? If it’s available online, you can broadcast it from your Mac

to your big-screen TV.

Using AirPlay Mirroring is easy: just open the Displays preference

pane (see

Displays

) and select Apple TV from the

drop-down menu (or the menu extra that’s enabled by default). The

hardest thing about AirPlay Mirroring is parting with $99 for the

required Apple TV.

You’ve been able to talk to your Mac and have it perform

actions for a decade. Now, Apple has raised the bar by giving your Mac

the ability to take dictation system-wide. That means that anything you

need to type you can instead

speak

to your attentively listening

Mac, and the machine will type if for you.

Dictation uses two things that might surprise you: your

location and your contacts. Your location is understandable (regional

accents and all), but contacts can seem positively creepy. Just what

is Apple after? Turns out Apple doesn’t care who your contacts are;

it’s interested in getting the names right when you use the dictation

software.

Apple’s version of dictation works a little differently than most

people expect. After you press the Fn (function) key twice, a little

microphone appears and you’re ready to start dictating. But the words

don’t appear on the screen as you speak. Instead, once you’re done

dictating, you click the Done button and the stuff you just said is sent

back to Apple’s servers and deciphered, then the passage pops up on your

Mac.

How well does it work? Here’s the “transcript” of the first

paragraph in this section:

“you talk to your form actions for a decade now apples raise the

bar in your Mac usually to take dictation system one that means

anything you need to type you can Cenesti to your listening machine

will type for”

Expect dictation to get better as time goes by.

That’s 10 nifty new features in Mountain Lion, but this list isn’t

comprehensive. There are a bunch of smaller improvements throughout OS X

in the various apps and system preferences; these changes are covered

throughout this book. To learn about changes to a specific app, for

example, flip to the section about that particular app.

The easiest way to start enjoying OS X Mountain Lion is to buy a new

Mac—the operating system is preinstalled, and you get a brand-new computer

to boot! If you’re one of the lucky ones getting a new Mac, you likely want

to learn how to get all your important data from your old machine to the new

one; see

Moving Data and Applications

for

details.

However, you don’t

have

to buy a new Mac to run

Mountain Lion, and since transferring your data is a little time consuming,

you might not want to. If your Mac meets Mountain Lion’s requirements

(explained next), you can simply upgrade your old Mac to Apple’s latest and

greatest. This chapter gives you the lowdown.

With every revision of OS X, Apple leaves some Macs behind,

and Mountain Lion is no exception. To install Mountain Lion, your Mac has

to possess a 64-bit Intel Core 2 Duo processor or better, be able to boot

into the OS X 64-bit kernel, and have an advanced

GPU (graphical processing unit). But those kinds of

requirements are hard to commit to memory—ask 100 Mac users what GPU

chipset their machine employs, and the vast majority of them will give you

a puzzled look (the people who

do

know the answer are

hard-core types and should be left alone).

So how do you find out whether your Mac is compatible with Mountain

Lion? The simplest way is to try to buy the software from the App Store.

If your Mac isn’t compatible, the App Store will tell you that the

software won’t run on that machine.

If you want to download the software once and install on multiple

machines, here’s a list of Macs that can run OS X Mountain Lion:

MacBook Pro 13-inch from mid-2009 or newer

MacBook Pro 15-inch from late 2007 or newer

MacBook Pro 17-inch from late 2007 or newer

MacBook Air from late 2008 or newer

Mac Mini from early 2009 or newer

iMac from mid-2007 or newer

Mac Pro from early 2008 or newer

Xserve from early 2009 or newer

You also need 2 GB of

RAM (which some otherwise compatible MacBooks and Mac Minis

might not have) and 5 GB of disk space. These are, of course,

minimum

requirements; you’ll be happier and your Mac

will run more smoothly if your computer has more RAM and disk space than

these requirements.

In addition to the hardware requirements, your Mac must be running

OS X 10.6.7 (Snow Leopard) or later. Why not, say, 10.6.3? Well, it’s

likely that you’ll be getting Mountain Lion from the Mac App Store, which

didn’t exist until 10.6.7 was released. If you’re running Snow Leopard,

just head to →

→

Software Update to

make sure you have the current version. If you’re running Leopard, you’ll

need to find a copy of Snow Leopard and install

that

before you worry about anything else.

Before deciding whether you actually want Mountain Lion, you

should do a little detective work. Like OS X Lion, Mountain Lion doesn’t

support PowerPC apps, so if you depend on one of those for day-to-day

work, you’ll likely want to avoid Mountain Lion or upgrade to new apps

before you install Mountain Lion. But how do you know which apps will and

won’t work?

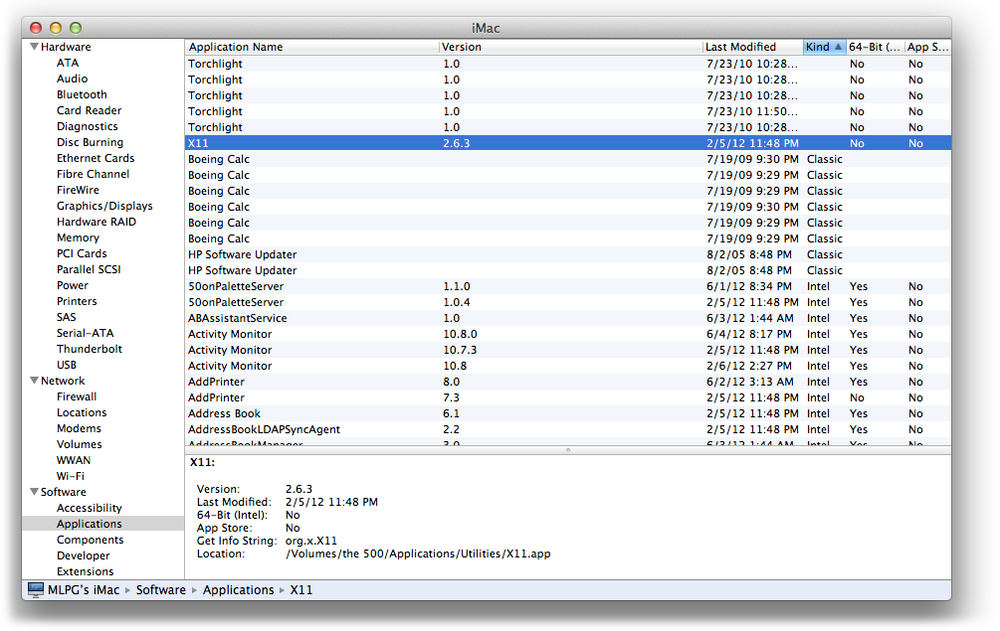

Luckily, there’s a quick way to get at this information.

Head to →

→

About This Mac, and

then click More Info to display a two-column window. The left column

contains a long list of entries that reveal specific information when you

select them. Scroll down to the Software section, click Applications, and,

in the right column, you’ll see a list of all the apps you have installed.

The list is sortable, so if you click Kind (as shown in

Figure 2-1

), the list will

organize the applications into five categories: Intel, Universal, PowerPC,

Classic, and (if your Mac just doesn’t know what kind it is) blank. If the

application you need says “PowerPC” or “Classic” next to it, then it won’t

run in Mountain Lion, so check to see if there’s a new version available

before you update your operating system. If you don’t need any of those

clunky PowerPC apps or if you’re able to upgrade to newer versions of

them, you’re ready for Mountain Lion.

Figure 2-1. Know what will run before you upgrade

If you’ve installed Lion, installing Mountain Lion will be

familiar, as the process is almost

exactly the same. If you’re unfamiliar with the process, this section

tells you what to expect.-

This is the first edition of OS X that’s App Store

exclusive. With Lion, you had an option to pay for a thumb drive with

the installer on it, but you can get Mountain Lion only from the App

Store. So what if you have a slow Internet connection or bandwidth

limits? Then you can visit your friendly neighborhood Apple Store and

download Mountain Lion while you browse all the cool Apple

hardware.

Regardless of whether you download the installer in the comfort of

your own home or use someone else’s bandwidth, the process of installing

Mountain Lion is dead simple. First, make sure you’re running the latest

version of Lion or Snow Leopard (if not, head to →

→

Software Update).

Then, open the App Store (click its icon in your Dock), purchase Mountain

Lion, and then wait for it to download.

Be warned: the Mountain Lion installer is 4.35 GB. With a 5 MBps

Internet connection (about the average speed in the U.S.), that will

take roughly two hours to download. So if you have a pokey Internet

connection or a bandwidth cap, you probably won’t want to download a

copy for each computer you have. In that case, you’ll find the Mountain

Lion installer in your Applications folder. Once you make a copy, you

can transfer it to any other authorized Mac you want Mountain Lion on

and run it without the hassle of a new download. (You’ll still have to

be connected to the Internet when you install Mountain Lion, but you

won’t have to download 4.35 GB of data again.)

Once

the download is complete, the Mountain Lion installer should launch

automatically. (If it doesn’t, you’ll likely find an alias for it in your

Dock and the original application in your Applications folder.) All you

have to do to get things moving is click the Continue button (

Figure 2-2

).

Figure 2-2. You have one option: Continue.

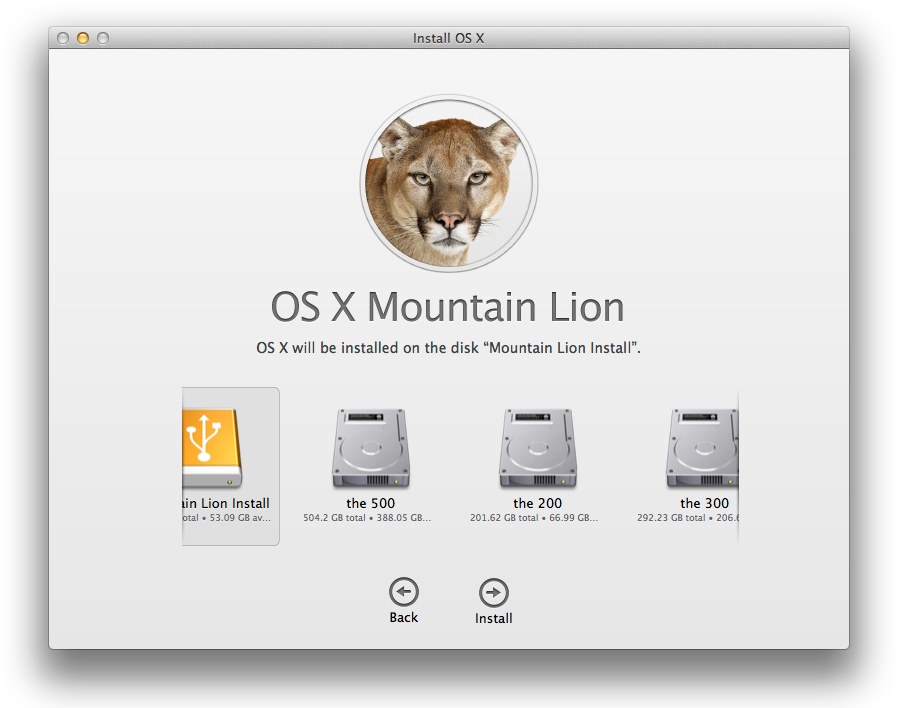

Once you take the plunge, you’ll be presented with a page

requiring you to agree to the software license. To install Mountain Lion,

you’ll have to click Agree twice: once in the Install OS X window and once

on a drop-down menu that asks if you

really

meant

that first click. After that, you’ll see a message telling you where

Mountain Lion will be installed. If you have multiple disks and don’t like

the choice the installer made, then click Show All Disks and you’ll be

able to pick the destination (

Figure 2-3

).

Figure 2-3. You get to choose the destination

Once you choose, click Install and then enter your administrator

password to continue. Mountain Lion will show you a status bar indicating

the progress of the install. A few minutes later, you’ll be notified that

you can either restart your Mac to proceed with the install or wait 30

seconds and let Mountain Lion restart for you. Instead of a regular

restart, your machine will shut down, reboot, and then proceed with the

installation process, which could take a while depending on how fast your

Mac is.

Mountain Lion can be installed on any drive (internal or

external) that’s formatted with Apple’s Mac OS Extended (

Journaled) file system. You can run Disk Utility from the

installer’s Utilities menu to format or inspect the drives on your

system.

After Mountain Lion is done installing, your Mac will

restart

again

using the new operating system, and

you’ll be ready to use your new OS. You might see a message that says

your email needs to be upgraded to work with the new version of Mail.

Other than that, you can get back to using your Mac just like you did

before you installed Mountain Lion (with some cool new features, of

course).

If you installed Mountain Lion on a blank drive or a

partition, your Mac will need some more information to get you up and

running. You’ll have to select your country’s keyboard layout and time

zone (Mountain Lion can do this for you; you’ll see a checkbox labeled

“Set time zone automatically using current location”). Then you’ll be

offered the opportunity to transfer data from another Mac (the next

section explains the process). If you choose not to, click Continue. If

you

do

want to migrate your data, see

Moving Data and Applications

to learn

how. Next, Mountain Lion will try to connect to the Internet. It’ll

automatically choose a network option, but if you’re not happy with its

choice, click the Different Network Setup button in the lower left of

the window and choose your preferred network. Once you’re hooked up to

the network, you’ll be asked for your Apple ID. You can skip this step,

but if you have an iCloud account, using that as your Apple

ID (by typing your ID and password into the provided box)

will let your Mac use the associated services without your having to do

any more configuring.

You might be reluctant to sign up for yet

another

online account. You probably don’t need

another email account, and you might wonder about the utility of

iCloud since you don’t see a place for it in your computing life. Now

is a good time to rethink that latter position. When Apple first

released MobileMe (the precursor to iCloud) the service handled Mail,

Contacts, and Safari bookmarks. In Mountain Lion, iCloud handles all

the stuff MobileMe handled

and

syncs photos and documents, and

lets you access your Mac remotely. In other words, iCloud is becoming

so central to the OS X experience that continued resistance is

futile.

After you enter (or create) your Apple ID, you’ll be

offered the opportunity to register your copy of Mountain Lion. The

information you type into the registration form will be used not just to

garner you a spot in Apple’s database, but also to generate an address

card for you in Address Book and to set up your email address for use

with Mail.

Mountain Lion will then ask you for some info on how and

where you intend to use your Mac. Once the data collection is out of the

way, you’ll be prompted to set up a user account. Mountain Lion will

generate a full name and account name for you; if you don’t want to use

its suggestions, you can type in your own names. You’ll also have to

enter a password and, if you wish, a hint in case you forget the

password.

With your account created, Mountain Lion will give you the

chance to snap a picture for the account with a webcam, choose a stock

image, or grab one from your picture library. Once that’s done, Mountain

Lion will configure your Mac using your iCloud information (if you use

the service). If you’re not an iCloud subscriber, don’t worry—your Mac

is ready to go. The things that iCloud configures automatically (like

Mail) just won’t be set up for you.

Not everyone will install Mountain Lion from the Mac App

Store; some folks will have a new Mac with Mountain Lion preinstalled.

If you’re one of these lucky ones, you aren’t interested in how to

install Mountain Lion. But if you’re upgrading from an older Mac or from

a Windows-based PC (getting data from a Windows PC onto your Mac is a

new, very nifty feature of Mountain Lion), you’ll certainly be

interested in getting that mountain of data from your old machine onto

your new computer. Apple has an app for that: Migration Assistant, which

can transfer files, settings, and preferences from your old computer to

your new one. After running Migration Assistant, your new Mac will seem

a lot like your old Mac. If you’re transferring data from a PC, your new

Mac won’t seem like your old PC, but it

will

have

the PC’s data on it.

You might not want to migrate your data from an old

computer right away: playing with a factory-fresh system is fun, and

migrating data isn’t a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity—you can do it

whenever is convenient. So toy with your new Mac for a while, and

then

migrate your data using Migration

Assistant.

When you run Migration Assistant, it can transfer the following

things to your new machine if you’re moving data from a Mac:

- Users

All your user accounts will be moved to your new

Mac. Accounts retain the same privileges (or restrictions) that

they had before. If you try to move over a user that already

exists on your Mac, you’ll have the option to either change the

account’s name or replace the existing user (as long as you aren’t

logged in as that user; if you want to import settings into your

account, first use System Preferences

→

Accounts to create a new user, log in as

that user, and then run Migration Assistant again). See

User Accounts

for more information.- Applications

All the applications in the Applications folder are

transferred, so you won’t have to reinstall them, and most should

retain all their settings (including any registration or

activation needed to run them).- Settings

Have a bunch of saved networks and passwords in your Network

Preferences? They all come along for the ride. So, if you’re used

to automatically jumping on the local WiFi hotspot, you’ll get on

without any extra effort. If your screensaver requires a password

to get back to the desktop, it still will. There are three

suboptions under Settings: Time Zone, Machine (computer settings

other than network or time zone), and Network; you get to pick and

choose the ones you want to move to your new machine.- Other files and folders

If your Mac has files strewn everywhere, even if they aren’t

where OS X expects them to be (the Documents directory), they’ll

be transferred.

If you stashed any files in the System folder, they

won’t

get transferred. But you shouldn’t ever

stash anything in the System folder, as it can get modified at any

time (by security updates and the like).

Migration Assistant

doesn’t

move the following items:

- The System folder

You’re installing a new system, so you don’t need the old

System folder to come along.- Apple applications and utilities

Migration Assistant assumes that every Apple application

(like FaceTime and iCal) on your Mountain Lion machine is newer or

the same version as the corresponding item on the Mac you’re

transferring data from, so those applications won’t get moved.

Instead, Migration Assistant will keep the preferences the same

and let you use the newer version. This is a problem only if you

hate the latest version of iMovie (for example). If you want to

use the older version instead, you’ll have to manually move it

over.

If you’re transferring data from a PC, Migration Assistant will

transfer the following:

IMAP and POP accounts from Outlook and Outlook Express

Contacts from Outlook, Outlook Express, and Contact home

directory (a folder in Windows for your contacts)Calendars from Outlook

Your iTunes library

Home Directory content (Music, Pictures, Desktop, Documents,

and Downloads)Localization settings, custom desktop pictures, and user

settings

How you begin the process depends on what type of machine

you’re migrating from. If you’re moving info from a PC, you’ll need to

point a browser to

http://support.apple.com/kb/DL1415

. From there, you can

download a program to install on your PC that makes the process

painless.

If you’re using a Mac, Migration Assistant was installed when you

installed Mountain Lion. As you’d expect, you need to be logged in as an

administrative user (or be able to supply the username and password of

an administrative user) to run Migration Assistant. Also, all other

applications have to be closed. So save all your work and quit

everything before you launch Migration Assistant. Then go to

Applications

→

Utilities

→

Migration Assistant to get started.

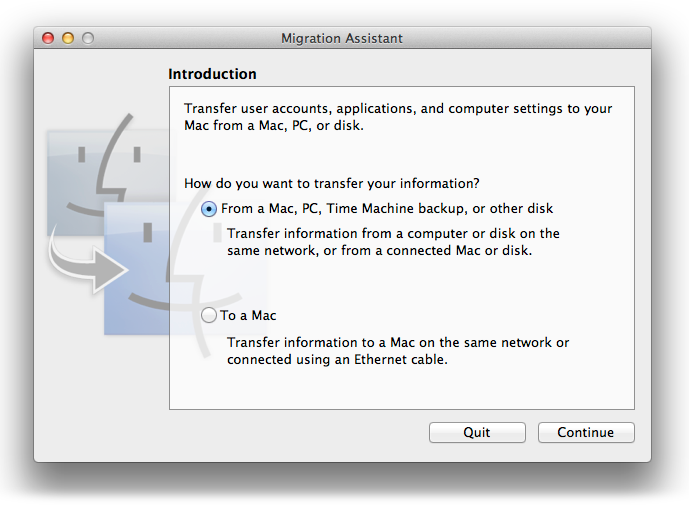

If you haven’t migrated data since the MacBook Air came

out, the process has changed a little bit. In the days before the Air,

Migration Assistant used FireWire Target Disk Mode (see the

Note

): you’d start the computer you wanted to

transfer data from in this mode, plug it into the destination Mac, and

then Migration Assistant took care of the rest. The good news is that

this method still works if you have two computers with FireWire; the

better news is that even if you don’t have two Macs with FireWire, you

can still use Migration Assistant. In fact, Migration Assistant offers

two ways to get your old data on your new Mac (shown in

Figure 2-4

):

Figure 2-4. Starting the migration process

- From another Mac, PC, Time Machine backup, or other

disk Choosing this option allows you to transfer data from a Mac

or PC that’s either wired to or on the same network (wired or

wireless) as your new Mountain Lion-powered Mac.- To a Mac

This option is the counterpart of the “From another Mac or

PC” option—you select this option on your source machine and the

other one on your destination machine.

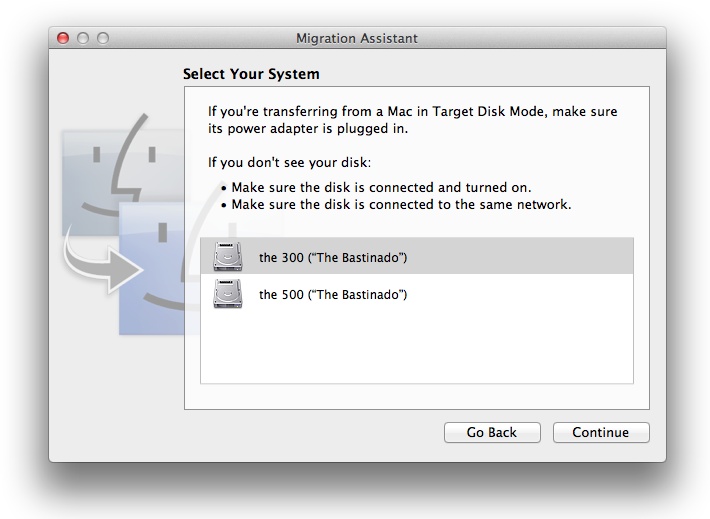

If you choose the first option, you’ll get two

more

options to choose between:

- From a Mac or PC

This is the option you’ll use if you want to transfer data,

well, from another Mac or PC. When you select this option and then

click the Continue button, the next screen will warn you that all

your applications must be closed. Save anything you’ve been

working on and click Continue, and your Mac will start looking for

other computers to transfer data from. Unless you’ve selected the

“To another Mac” option (discussed above) on the computer you want

to transfer data from, it won’t find any. No problem: Migration

Assistant will keep looking while you fire up Migration Assistant

on the other machine and select “To another Mac” on that computer.

Once both computers are ready to go, you’ll see something like

Figure 2-5

.

Figure 2-5. Transferring data from a disk

Click Continue and you’ll see a passcode. You don’t have to

write it down or remember it; you just need to make sure it’s the

same as the one displayed on the machine you are transferring data

from. (The passcode won’t show up on the data-donating machine

until the exchange has been initiated by the Mac you’re moving the

data

to

.) Verify that the numbers match, and

then click Continue. Next, you get a chance to decide what you

want to migrate (see

Fine-Tuning Data Migration

). Click Continue, and your

data will be transferred.- From a Time Machine backup or other disk

If you choose this option, your new Mac will scan all

attached drives and then present you with a list of drives you can

migrate data from. Click the one you wish to use, and then click

Continue. By default, Mountain Lion will transfer all your

relevant info, but you can change that behavior (see

Fine-Tuning Data Migration

).

If both Macs have FireWire, choose “From a Time Machine backup

or other disk” and then restart the Mac you want to get data

from

in FireWire Target Disk Mode. You do this by

holding down the T key while the computer boots until you see a

FireWire symbol dancing on the screen.