Poison (7 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Heavy footsteps up the stairs. Sukhwinder Dhillon entered the bedroom. Even at the best of times, the first night is an awkward moment for a young Indian woman in an arranged marriage. Sometimes new brides are able to put off sex until getting to know the groom better. Sometimes there is no option. Sarabjit knew there would be none with Dhillon. She was afraid. He sat down on the bed, the mattress straining underneath him. He was quiet at first, the only sound horns coming from cars and scooters in the darkened alleys below. They had barely even talked before, not even at the wedding, where the ceremony requires no speaking from the couple, or at the reception, where Dhillon drank copious amounts of whisky with his male friends and danced with them in a circle.

“I am happy, you know, that you are my wife,” Dhillon said. Sarabjit murmured quietly, inaudibly, staring at her bare feet. She was unaccustomed to a man even having the familiarity to look her square in the eye. She wanted to cry.

Dhillon continued. “We will get to know each other much better, and it will make it much easier.” Sarabjit nodded. “And now that we are husband and wife, we can spend the night. Why don’t you take off your clothes?”

Sarabjit said nothing. She expected this bluntness, but it still shocked her. “It would make me happy,” he said, “if you would undress for bed.”

It went on like this, Dhillon asking her to disrobe:

Kaprey laah dey

. The thought of running out on him did not cross her mind, it was beyond the pale. It would humiliate her family, her parents would be ostracized in the community, likely asked to leave their village. Her in-laws would probably burn her for it. All she could do was stall.

Kaprey laah dey

.

Kaprey laah dey

. The thought of running out on him did not cross her mind, it was beyond the pale. It would humiliate her family, her parents would be ostracized in the community, likely asked to leave their village. Her in-laws would probably burn her for it. All she could do was stall.

Kaprey laah dey

.

Finally, she slid off the lehnga, the thin scarf, then her blouse, pants. Dhillon removed his shirt and undershirt, and pants. Unprepared both mentally and physically for what was happening, Sarabjit felt the weight of the large body on top of her, then a painful burning sensation as he entered her. Later, they lay on the bed. It was all very odd, she thought. She felt nothing.

Dhillon, his mind now freed, began to chatter. Sikh men are often considered chauvinistic by Western standards, not inclined toward expressions of affection for their wives in either word or deed. Indians joke that men feel no shame urinating in public, but it’s taboo to kiss a woman in front of others.

“I am a very experienced man, you know,” Dhillon said. “I was married for many years.”

Sarabjit knew he was married before. Why was he talking like this? He lamented his lot in the world. “The Punjabis see me visit, and all they see is Canada. They don’t see me as a person. The fact is, I could bring 10 girls back just like you. They were offering me even younger girls, 16, 17 years old.”

Sarabjit felt the muscles in her face tighten in anger. She had decided at the wedding that no matter how bad it all seemed, she was strong. She would will herself to make her life work, no matter what. But now, in the darkness, with her virginity—in Indian culture, her most precious possession—painfully torn away by a man she was rapidly growing to hate, she knew the story was not going to end well. She closed her eyes, tuned out Dhillon’s rambling words and the clanging and hooting of the streets below, thought of quiet Panj Grain, and forced herself to sleep.

Dhillon and Sarbjit signed marriage papers in Ludhiana—he had the choice of declaring his status as unmarried, widower, or divorced; he lied and checked off unmarried. And then, five days after their wedding, Dhillon drove the Maruti along the ragged roads, Sarabjit beside him, and his niece, Sarvjit, and his two daughters in the back. This was a day Dhillon had tried to put off as long as possible—visiting Parvesh’s parents. His young daughters yearned to see their grandparents. Soon they arrived in Parvesh’s old village, called Sahkewal, a half hour through heavy traffic from Birk Barsal. Dhillon’s only contact with Parvesh’s parents since her death was when he had, insultingly, mailed Hardial and Hardev Grewal their daughter’s ashes.

Hardial, Parvesh’s mother, wasn’t surprised by anything Dhillon did, not anymore. She and Hardev had lived with Dhillon and Parvesh while visiting Canada for long stretches. His behavior after her daughter’s death only confirmed in her mind the evil that defined her son-in-law. It was not uncommon for a Sikh man to treat his in-laws with just enough indifference to show who wielded the power, but Dhillon took it to an ugly extreme. Hardial knew, long before she saw it herself, that Dhillon beat Parvesh. Harpreet, the older child, once told her grandmother so. The girl saw her father hit her mother with an object but she never told anyone about it because her dad said he would kill her if she repeated the story. Was that just a child’s imagination? No, Hardial saw it for herself. She had cringed in fear at the house on Berkindale Drive in Hamilton when Dhillon turned on Parvesh, screaming at her, threatening to kill her. She waited in horror for the blows that followed, for Dhillon to seize Parvesh by the throat. There were times she stood in front of Parvesh, trying to protect her, but Dhillon had merely swatted her out of the way.

In the car with Sarabjit, Dhillon drove in silence, then finally spoke. “Hardial may say some bad things about me,” he warned. “Whatever she says, don’t believe her.”

Why does he say things like that?

Sarabjit wondered. She was suspicious, to say the least, and fearful. The Maruti pulled up to the house. Dhillon got out and saw Hardev, Parvesh’s father. “You never visited us when our daughter was alive. So why now?” he asked. Inside, Hardev took Dhillon’s niece and his granddaughters to a different room, and now it was just Hardial, Dhillon, and Sarabjit together in the living room. Dhillon tried to make small talk. Parvesh’s mother could barely look at him, the very sight disgusted her. She looked at Sarabjit.

Sarabjit wondered. She was suspicious, to say the least, and fearful. The Maruti pulled up to the house. Dhillon got out and saw Hardev, Parvesh’s father. “You never visited us when our daughter was alive. So why now?” he asked. Inside, Hardev took Dhillon’s niece and his granddaughters to a different room, and now it was just Hardial, Dhillon, and Sarabjit together in the living room. Dhillon tried to make small talk. Parvesh’s mother could barely look at him, the very sight disgusted her. She looked at Sarabjit.

“Be careful,” she said. “He killed my daughter. He’ll do the same thing to you. He’ll take you over there and do the same thing.” Sarabjit stood there as Dhillon and Hardial went at it, arguing. Dhillon tried to turn the tables. What about you, Hardial? You were never a good grandmother. Never! How come you never came to Canada to visit Harpreet when she was sick? Well?

Hardial was livid. She called Dhillon

kanjra

, Punjabi for bastard.

kanjra

, Punjabi for bastard.

“My granddaughters!” she shouted. “You might as well kill both of them, too. You killed my daughter, why not my granddaughters?” Dhillon motioned to Sarabjit. We’re leaving. Did he not predict the crazy old woman would lie about him? Dhillon herded the girls, his niece, and Sarabjit back in the car. As they drove away, Sarabjit didn’t want to believe Hardial, but she had already seen enough of Dhillon to assume the worst. She reflected on the nickname Dhillon’s friends called him: Jodha. Brave warrior. Right.

Sarabjit satisfied his appetite for sex as she was expected. Dhillon received it on demand nearly every day. On Thursday, April 27, he left Sarabjit in Birk Barsal. He had to drive two hours to Chandigarh, the capital of Punjab. “Business to take care of.” He did not go to Chandigarh. Instead he picked up his friend Dulla and they drove to a farm village called Tibba. It was surrounded by fields of rice, corn, and sugar cane. Brick and clay homes clustered tightly together on cobblestone streets and, at the end of a long dirt path, was a funeral pyre beside the Gudwara temple. Elderly women sat on the ground washing pots, ignoring flies buzzing around their faces, in a courtyard that blocked out wind and trapped heat like an oven. Dhillon and Dulla entered the home of a man named Rai Singh Toor.

Rai Singh had heard that Dhillon was in the area and interested in remarrying following the death of Parvesh in Canada. Both Rai Singh and his wife desperately wanted to marry one of their two daughters to an Indo-Canadian, and then ultimately join her overseas. Nearly everyone in Tibba wanted to get to Canada. Those with a relative overseas erected proud displays on their homes to show it, elaborate gates or family crests that stood out like flashing neon in the dusty village. These were called “dollar homes,” meaning the family received money from abroad—foreign currency, not mere Indian rupees. Dhillon and Dulla looked over Rai Singh’s daughters. The youngest was named Sukie. She stood off to one side in the courtyard. Dhillon moved closer.

“You’re pretty,” he said. “I should marry you.” Sukie wouldn’t turn 19 for another two weeks. Her sister, Kushpreet, was slightly older. Tradition says the father must marry off his daughters in descending order of age. Shown Kushpreet, Dhillon looked her

over, said nothing, and nodded in agreement.

over, said nothing, and nodded in agreement.

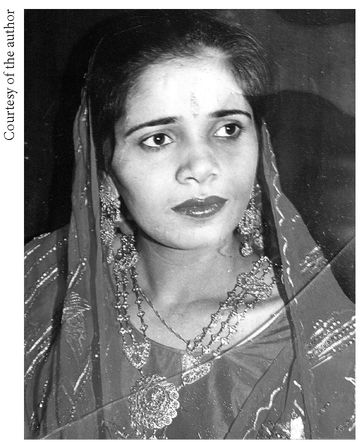

Kushpreet Kaur Toor, Dhillon’s third wife

“The marriage will be held in 12 days,” Rai Singh announced. Dhillon agreed, then saw Dulla’s glare, the ever-present revolver handle sticking out of his pants. That wouldn’t work. Dhillon remembered he had a flight back to Canada that left in 12 days.

“Let’s get this over with,” Dulla said. Rai Singh agreed to speed up arrangements with the temple. They could be married in three days, on April 30, then Dhillon could return to Canada, finalize immigration papers for Kushpreet, and bring her to the promised land.

Dhillon and Dulla left the village and returned to Ludhiana, where Sarabjit waited. Three days later, Dhillon told Sarabjit he had to leave again, this time for New Delhi. He always had some place to go. This time he was signing deals to import used cars from Canada to sell in India.

Dhillon and Dulla instead drove an hour to his next wedding, at the Manjal Hotel in a village called Sahnewal. Dhillon made sure his marriage to Kushpreet was registered in a neighboring district called Moga, to disguise his marriage to Sarabjit. There were 150 guests, Dhillon collected his dowry, got drunk on whisky. The wedding reception over, Kushpreet returned to Tibba, festooned with the ceremonial maroon and ivory-colored bracelets, her palms painted red. Dhillon was anxious to consummate the nuptials, but Rai Singh would not allow his daughter to live with Dhillon until immigration papers were finalized—to ensure that Kushpreet’s, and the family’s, ticket to Canada was secure. If Dhillon slept with his daughter, and

then left her, she would lose her value in the eyes of the community and he would never get to Canada. Dhillon still had Sarabjit waiting in Birk Barsal to provide sex over the remaining nine days.

then left her, she would lose her value in the eyes of the community and he would never get to Canada. Dhillon still had Sarabjit waiting in Birk Barsal to provide sex over the remaining nine days.

On May 9, three months after Parvesh died, 33 days after marrying Sarabjit, and nine days since exchanging vows with Kushpreet, Dhillon’s flight took off from New Delhi. When he was preparing to leave, Dhillon told Sarabjit to be patient. It wouldn’t be long now, he would bring her to Canada. He phoned Kushpreet and told her the same thing. Everything would work out. Sarabjit stayed at Dhillon’s home in Ludhiana; Kushpreet remained with her parents in Tibba. When Dhillon arrived back in Hamilton with his daughters, rumors of his exploits in India spread in the local Sikh community. Marrying a woman so soon after Parvesh’s death was scandalous. Dhillon lamented that he had no choice but to remarry quickly. He needed a wife to look after the girls. The rumors persisted. Was there a

third

wife? On May 23, Dhillon phoned an immigration lawyer in Etobicoke, near Toronto. He was interested in bringing his new wife, Kushpreet Kaur Toor, to Canada. He said nothing about Sarabjit.

third

wife? On May 23, Dhillon phoned an immigration lawyer in Etobicoke, near Toronto. He was interested in bringing his new wife, Kushpreet Kaur Toor, to Canada. He said nothing about Sarabjit.

Dhillon had received $1,100 a month widower’s pension since Parvesh’s death. He was collecting about $5,000 a year in revenue from his family’s farm in Ludhiana. He was buying and selling used cars in Hamilton, grossing $38,500 between October 1994 and September 1995. He received compensation from a 1991 workplace “accident,” now worth about $9,000 a year.

There was a stack of mail on the table in Dhillon’s house. A friend of his in Hamilton, a man named Ranjit Khela, had collected it for him while he was away. Near the top was a worker’s compensation form. It was dated May 2. It asked if Sukhwinder Dhillon was working again. He checked off the “no” box. He dated the form May 10 and mailed it in. It was all small change.

The biggest windfall was to come—Parvesh’s life insurance money. A cool $200,000.

Other books

Beyond the Hell Cliffs by Case C. Capehart

Jam and Roses by Mary Gibson

More Stories from My Father's Court by Isaac Bashevis Singer

The Mosts by Melissa Senate

Madison's Music by Burt Neuborne

The Power of the Legendary Greek by Catherine George

A Little Wanting Song by Cath Crowley

Diane Vallere - Style & Error 03 - The Brim Reaper by Diane Vallere

Trial By Fire by Coyle, Harold

Crosstalk by Connie Willis